Please note: If on devices you click on links to images and/or text that do not open if they should, just slightly scroll the screen to re-enable the function. Strange behavior of WordPress.

Black lines open up to colors

This page examines some paintings that Mondrian created in New York City. These works will lead to New York City, a work preamble of the last two paintings Broadway Boogie Woogie and Victory Boogie Woogie.

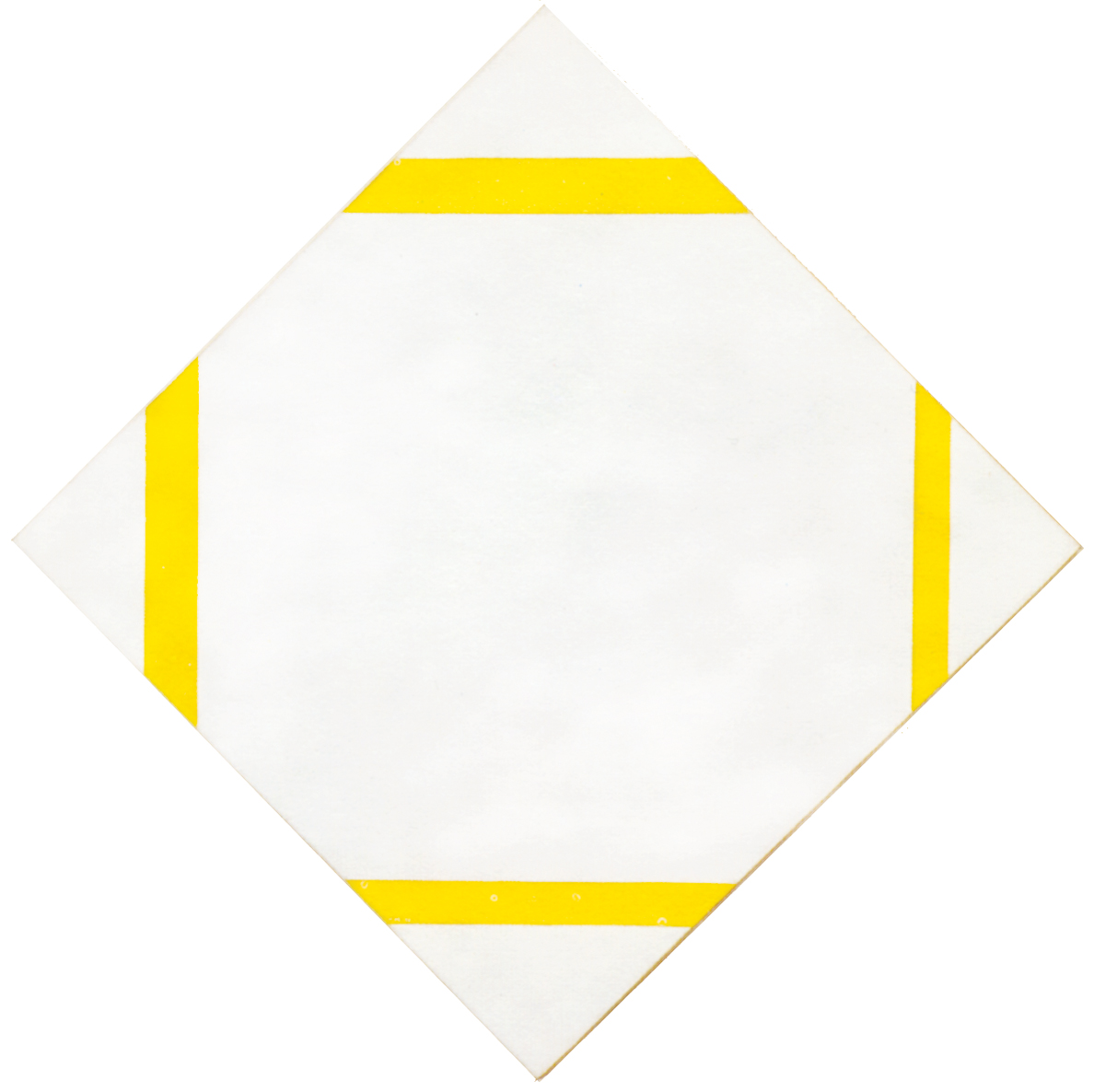

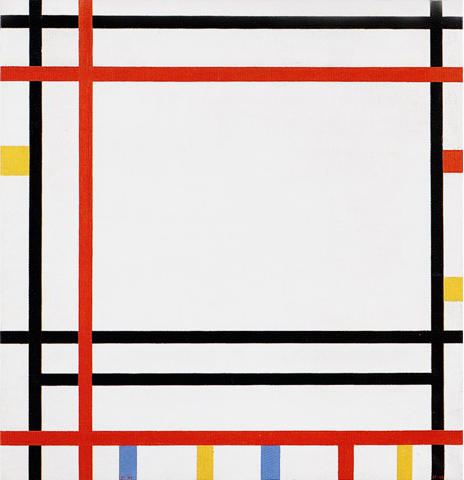

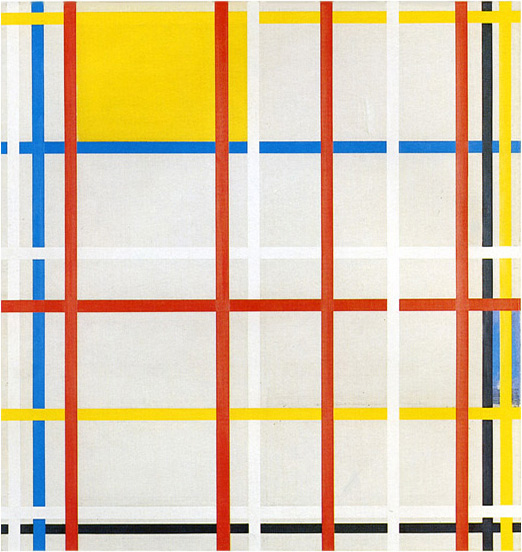

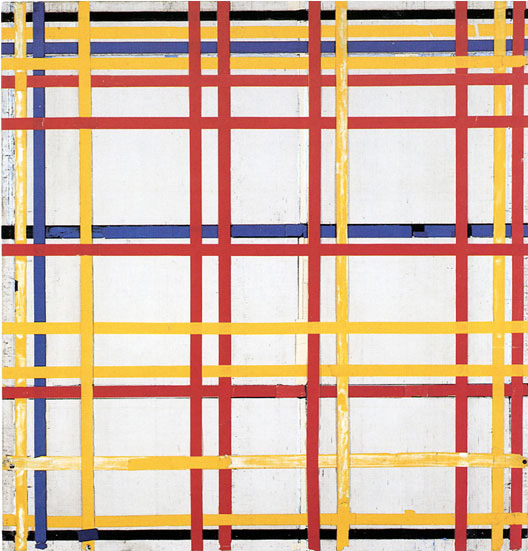

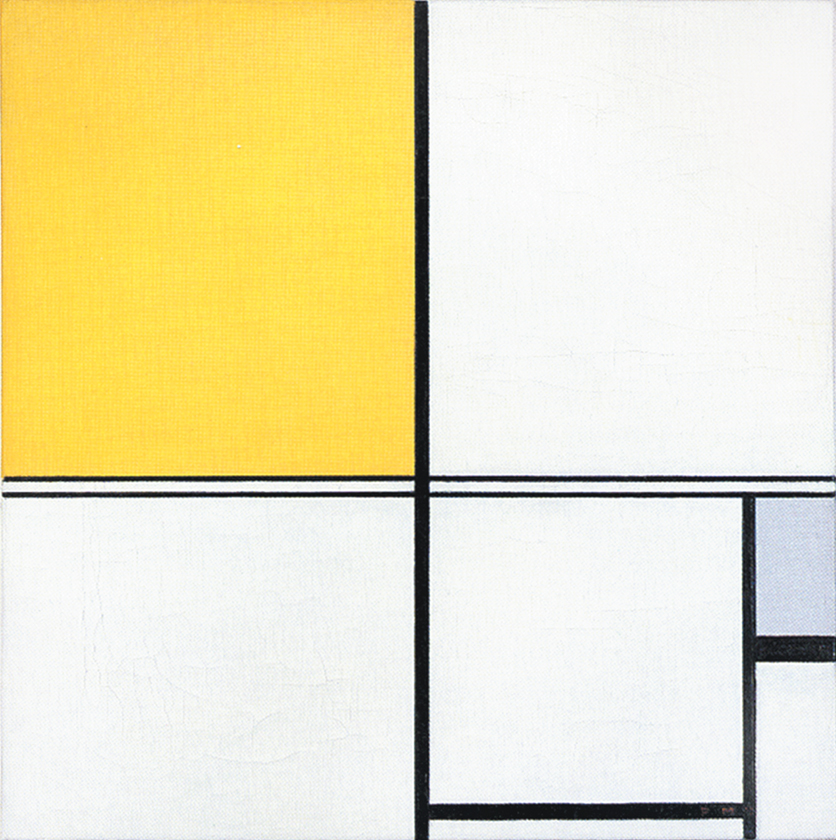

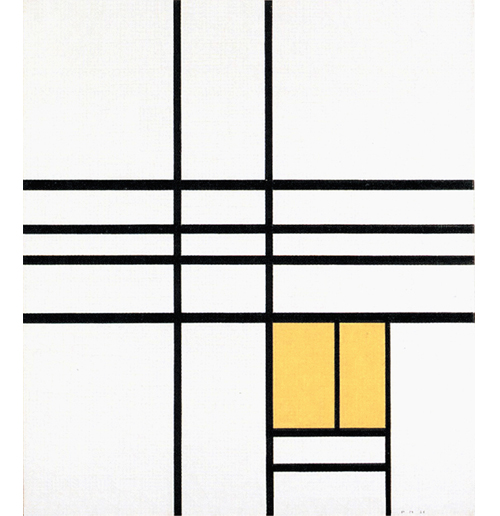

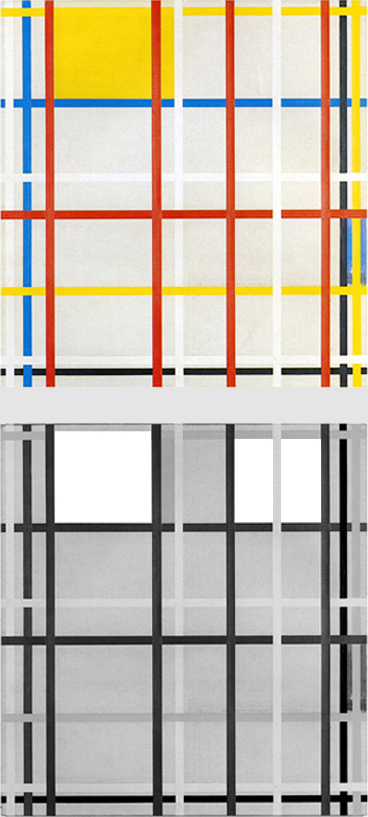

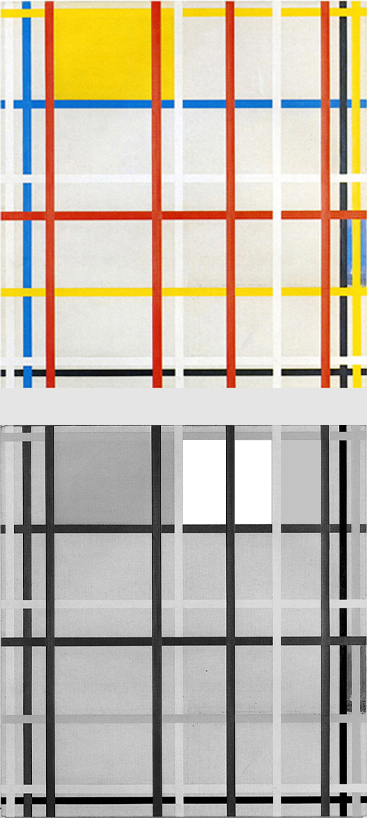

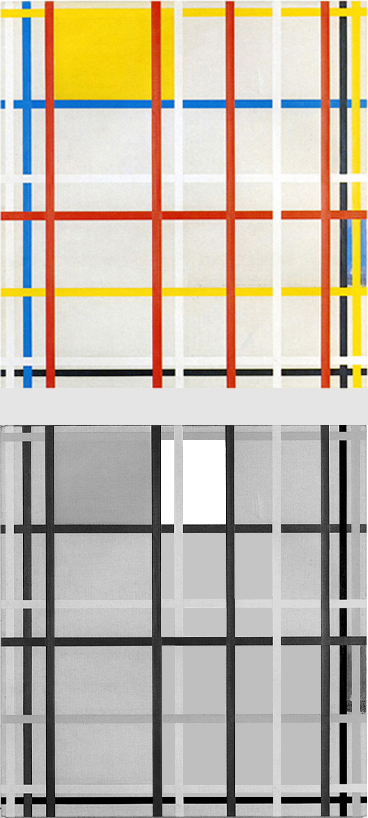

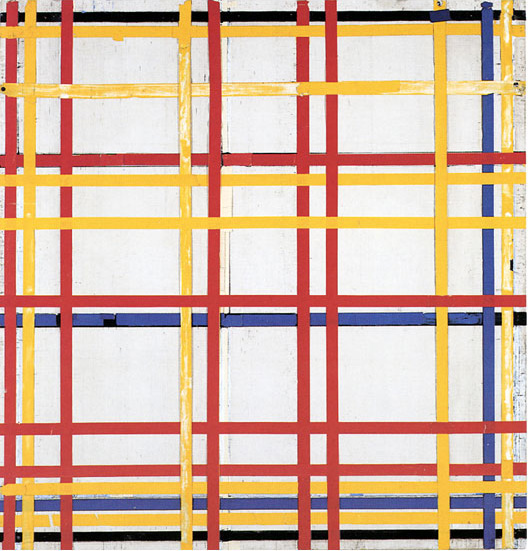

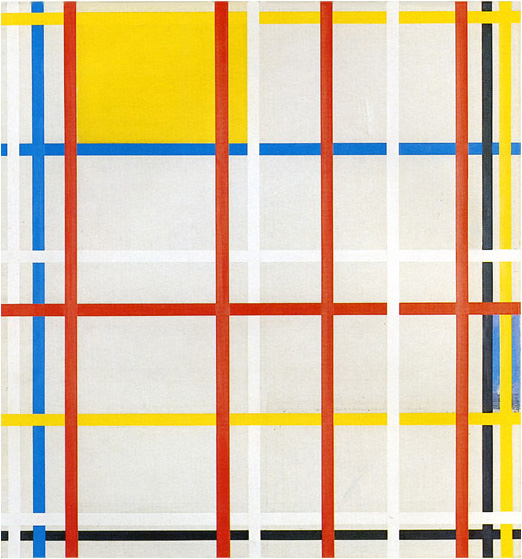

After Fig. 1 where the artist introduced red lines, new works show the use of white, yellow, red, blue and black lines (Fig. 2, 3, 4):

In 1933 the artist had used yellow lines. The blossoming of colored lines constitutes now a further development in the process of opening up the compositions to multiplicity which had begun in 1934 in terms of form with a progressive increase of black lines:

A new tool

In addition to brushes and oil paints, New York City offered Mondrian a new tool to use in producing his works, namely colored tape, which allowed him to change the positions of the lines and thus work on the composition with greater flexibility. Once a satisfactory configuration had been obtained, it could be made permanent in oils.

Some critics have suggested a connection between the use of color for the lines and the availability of colored tape. I do not believe that this tapes suddenly triggered a change that started some ten years earlier as the analysis in the previous pages clearly shows.

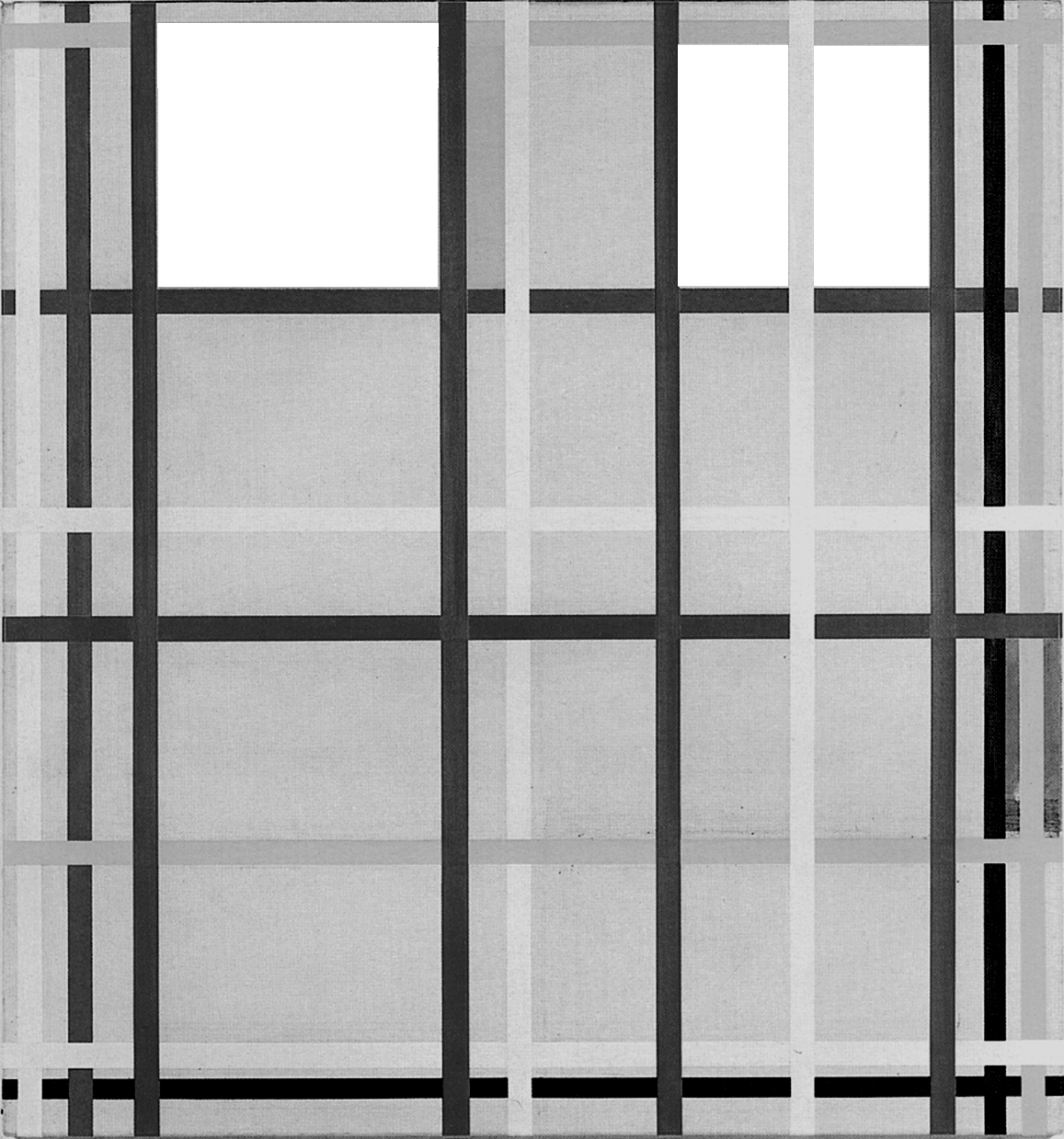

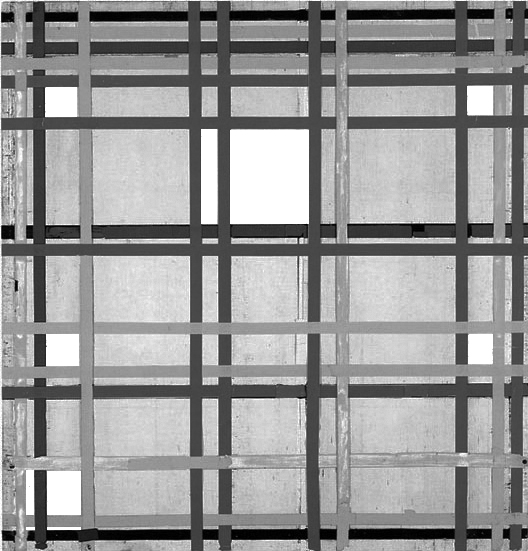

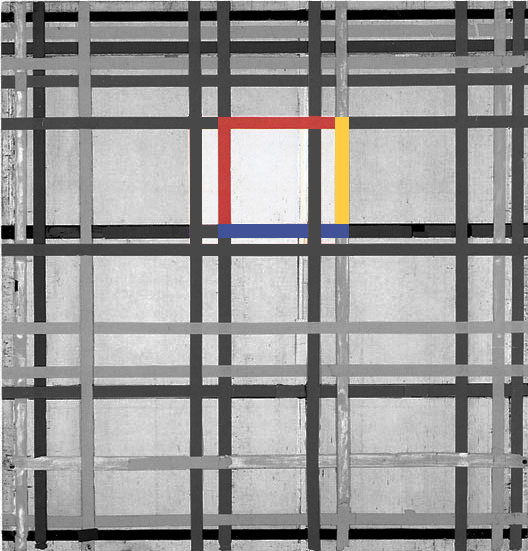

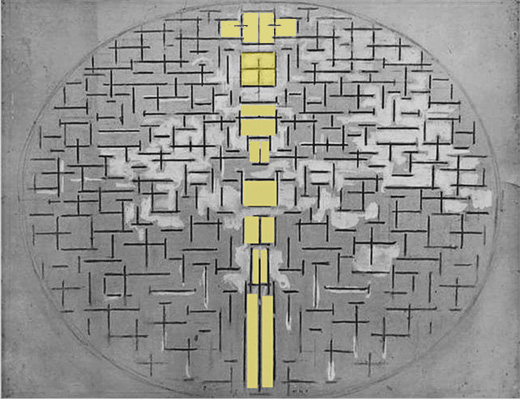

New York City 3

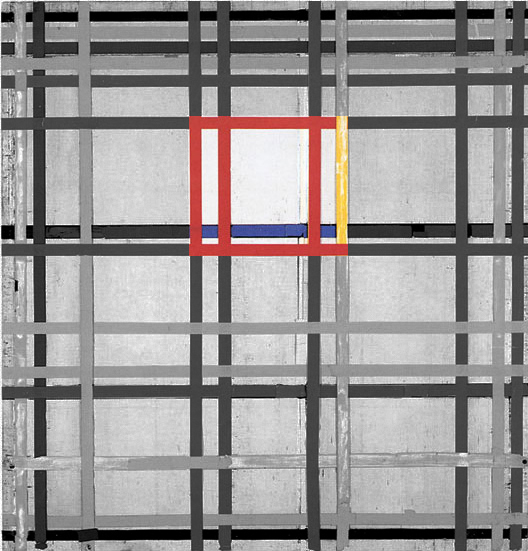

Details supplied by Joop M. Joosten suggest that the painting could be a reworking of a canvas begun in 1938. Mondrian used tape during his work on this composition but never got round to the definitive application of paint:

New York City 3, 1941 (Unfinished)

Pencil, Charcoal, Oil on Canvas, cm 110,5 x 116,8

From what can be seen of this canvas today, Mondrian used yellow, red, and blue lines at the same time accompanied by two black lines and, unusually enough, also five white lines. The latter appear such because the canvas, – if I remember rightly from the time I saw the original at the NYC Sidney Janis Gallery – was never primed and is therefore ivory in color.

The combination of lines of different colors produces forms that change constantly in appearance:

The different visual weights of the colored lines emphasize certain forms with respect to others. The areas marked out with white lines are less conspicuous than those with red. A yellow plane can be seen in the upper left section and a blue one of uncertain nature on the right edge of the canvas. The yellow plane extends horizontally but is led by a red vertical line on the right toward a square proportion formed by another red line on the left and a blue line below (Diagram A):

In this plane, which is in a state of dynamic equilibrium between the horizontal expansion of the yellow and the concentrating input of the red line, the opposing directions attain equivalence for an instant in a square that combines in itself the three primary colors.

Right of this square another square area can be seen formed by a yellow line at the top, a blue line below and two red vertical lines (Diagram A).

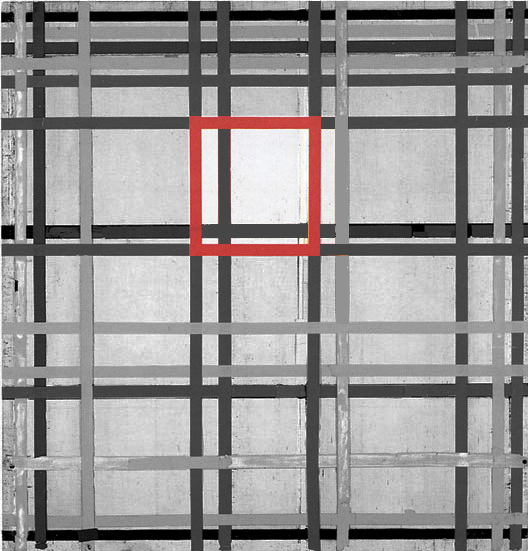

We therefore have another equivalence of yellow, red, and blue. With respect to the first square, however, the inner field of the square is no longer yellow, being crossed by a white vertical line. The latter works with a second white line on the left to generate a third square form (Diagram B):

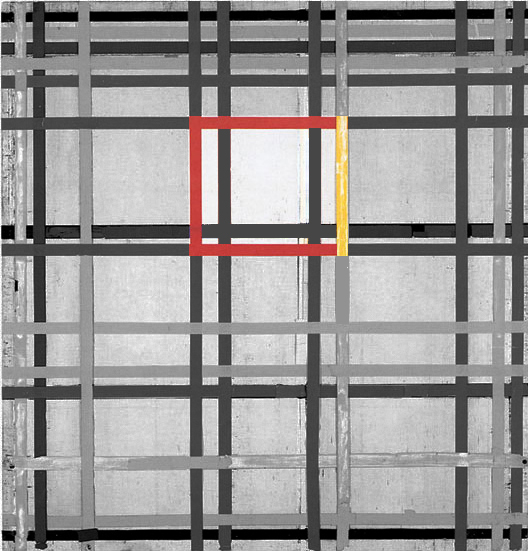

As noted above, due to the visual weights of the colors, the square on the right side of diagram A stands out more than the square highlighted in diagram B. The silent white line that subtly disturbs the equilibrium of the square seen in diagram A is strengthened (becomes red) inside the square shown in diagram B. Observe the two squares in sequential order. The red line dividing the square of diagram B seems designed to tell us that the two squares previously achieved (Diagram A) are dissolving, which is what happens in diagram C:

An area of horizontal predominance (the yellow plane) is transformed into an equivalence (Diagram A) that then dissolves gradually (Diagrams A, B, C):

We note once again that different parts of a Neoplastic composition prove to be a single entity represented in its process of becoming. The content of a Neoplastic painting stretches far beyond the limiting and partial descriptions that verbal language can supply. The reading of a composition must be reiterated in order to capture all of its substance. Through bright and exuberant colors, above all on beholding the original paintings, the eye addresses a dynamic set of relations. The eye reads and rereads the same pathways, which evoke new relations every time and thus express a rich and varied reality.

The composition presents other square forms such as the one shown in diagram D or the square area highlighted in diagram E:

The square proportion shown in diagram D is formed by red, blue and black colored lines and therefore appears more achieved and solid than the square shown in diagram E where the right vertical line of white color appears faint against the ivory-colored background and therefore seems to open the square to the right. The inner field of the large square (Diagram D) is crossed by lines of different color that generate a variety of more or less obvious rectangles.

Traveling along the lines, we find new forms balanced between a slight vertical predominance which then become a horizontal rectangle and vice versa. Uncertain squares scarcely have time to manifest themselves before being pulled away by the rapid continuity of the lines.

The dynamic flow of the lines causes pressure and crisis for the equilibriums manifested for an instant through the various squares of different colors. While the eye pauses on a single form, space moves anew with an alternation of expansion and concentration. The planes are barely visible when formed by white lines. Unlike previous compositions with only black lines, the greater or lesser permanence of the square forms now depends also on the color of the lines forming them.

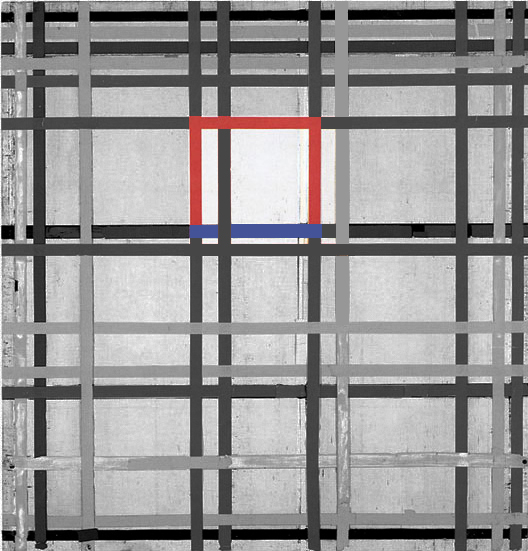

The blue plane on the right is so markedly vertical as to look almost like a segment of line. This plane appears designed to compensate for the absence of blue lines in that area of the composition and, at the same time, to endow the whole with a certain weight and counterbalance the horizontal yellow plane:

With respect to the square seen in the lower section of diagram C1, the blue plane is in the same position as the small accents of color in the canvases based on Layout C.

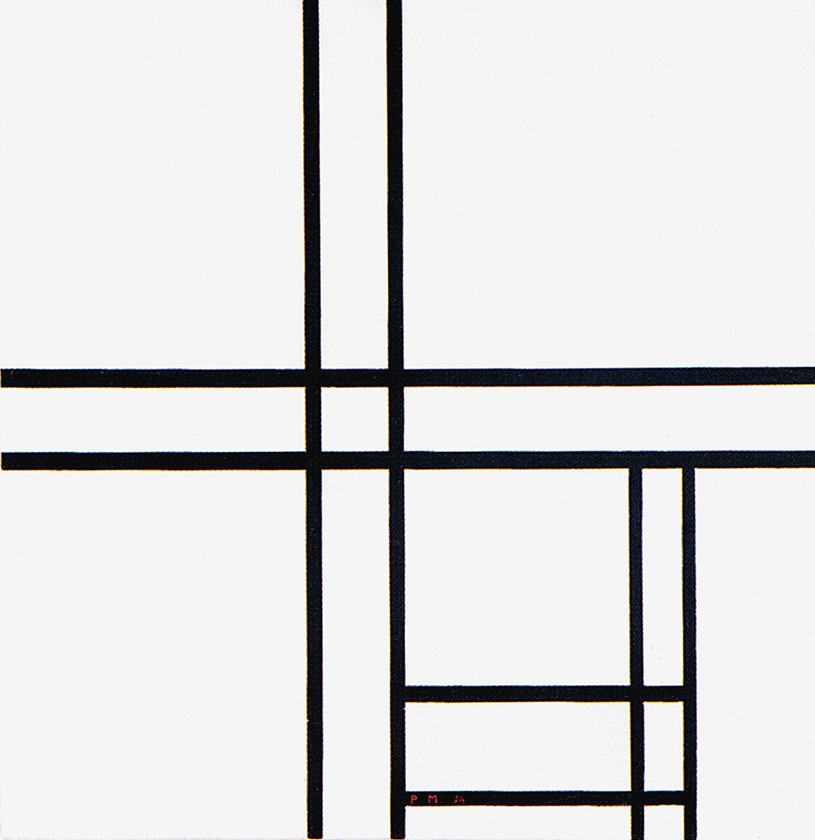

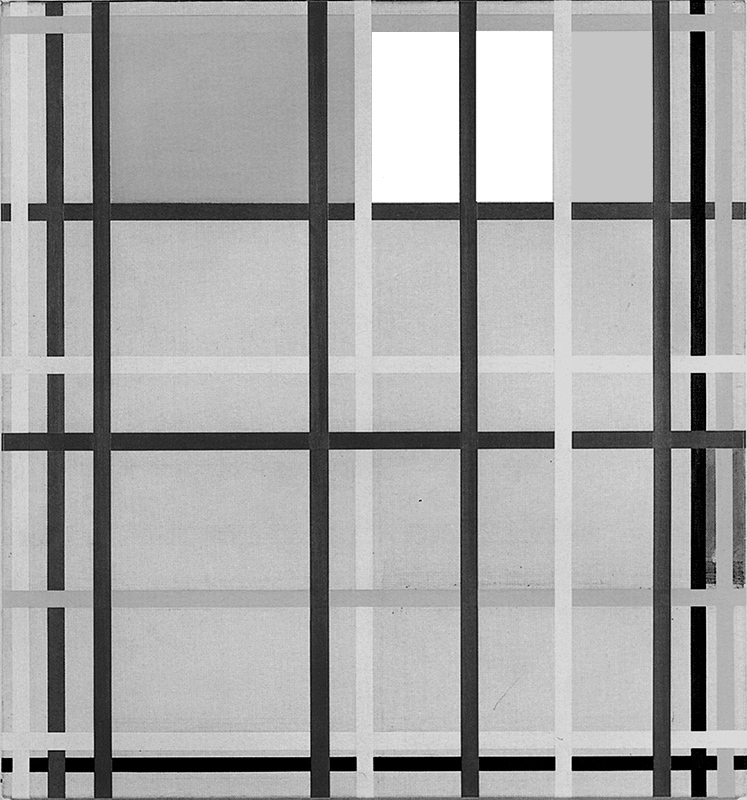

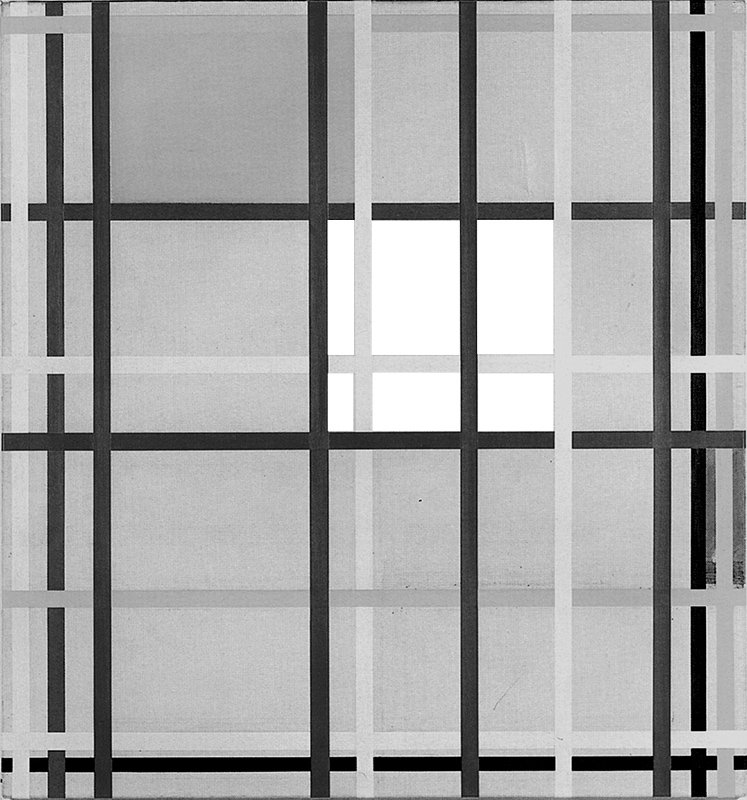

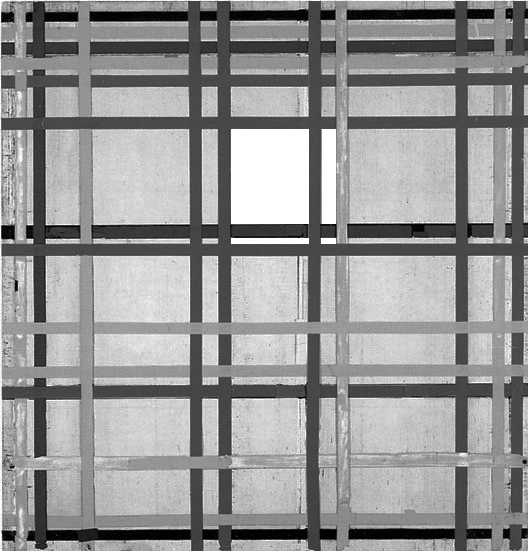

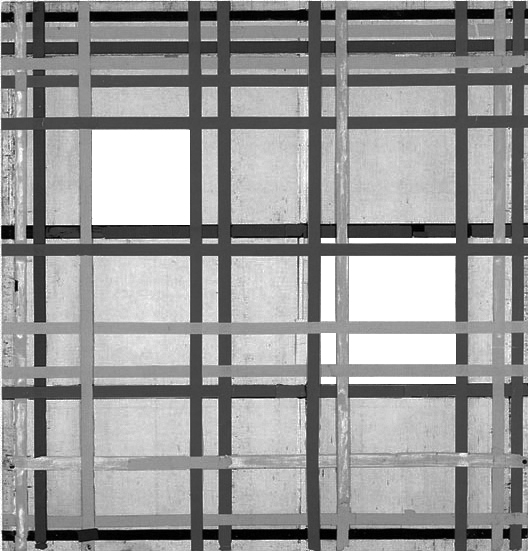

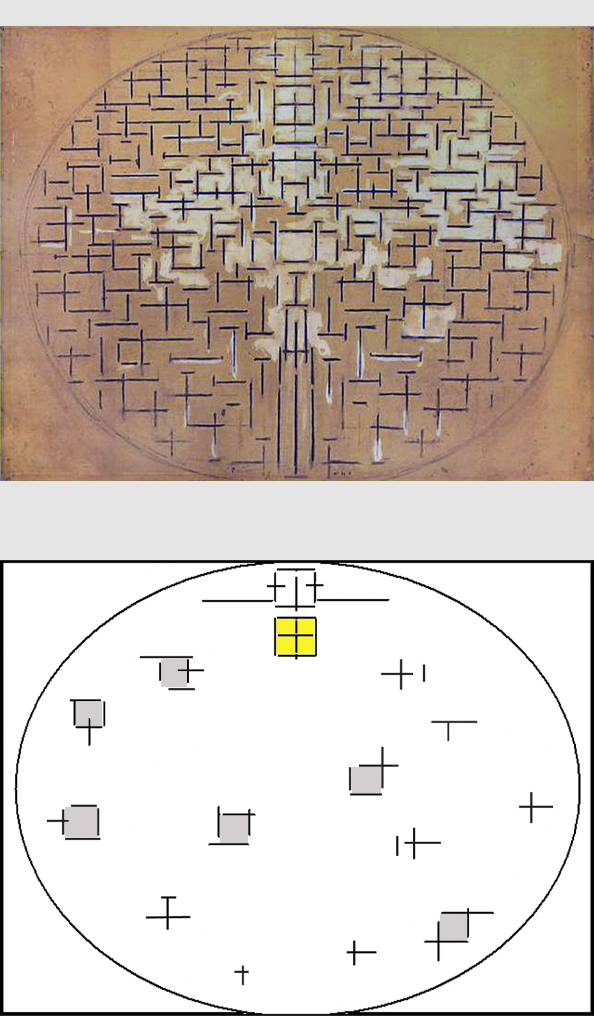

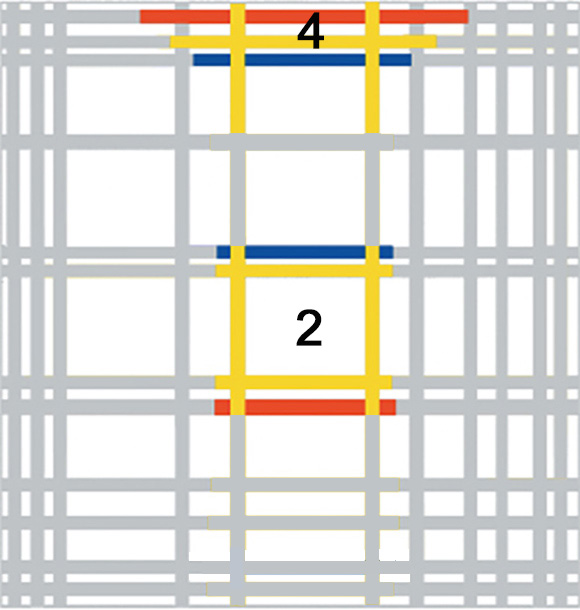

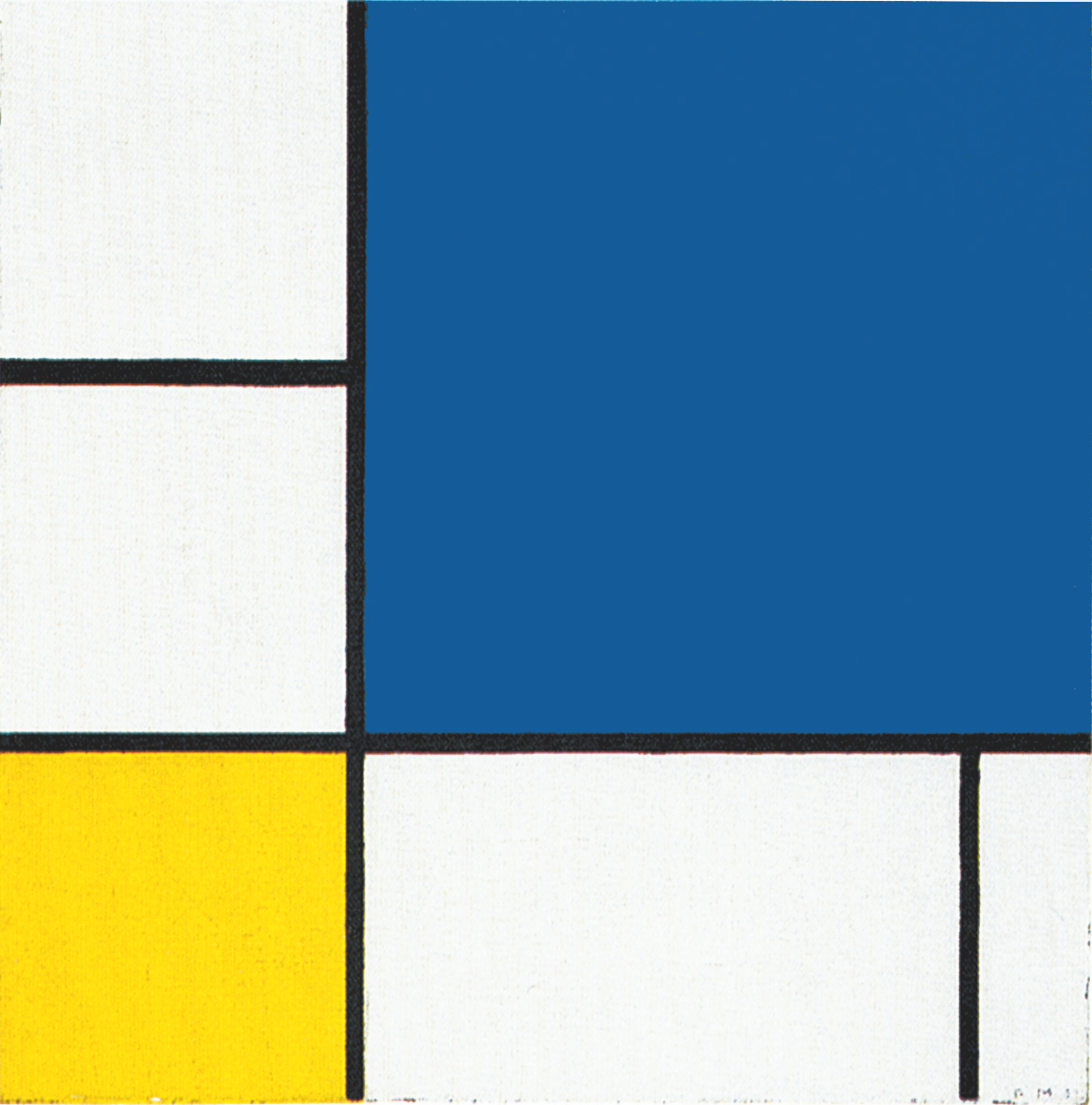

New York City 1

Curator Meyer-Büser from Kunstsammlung NRW, Germany has suggested that, according to a photograph taken in Mondrian’s studio a few months after the artist’s death, this painting could have been hanged upside-down ever since as shown here in Fig. 3 – Old position:

We cannot be sure of this because it is an unfinished work without signature but I personally think that Meyer-Büser’s assumption makes sense. I am therefore considering this work in the new position (Fig. 3 New position). Even so, there are no significant changes in the way the composition shall be interpreted. What actually would change in the new position is the fact that, due to the increased amount of lines and therefore of visual weight in the higher part of the canvas, the whole composition acquires strength and tension.

Like Fig. 2 Fig. 3 presents a multiplication of space with fourteen horizontal and ten vertical lines generating a complex set of varying relations between opposites. There are no longer any colored planes in this composition.

We contemplate a multiplicity of relationships between opposite lines where now one and now the other direction prevails, then find square proportions, i.e., situations where opposites reach the equivalence. Diagrams A, B, C:

The square proportions are then always challenged by sudden horizontal or vertical expansion, the presence of one color or another.

As in Fig. 2, the squares appear to be formed by more than four lines. They thus expand and contract, alluding to the loss and subsequent re-establishment of a balanced relationship between opposite lines of different colors. The squares appear now more precarious than those formed by single lines.

A greater density of elements is concentrated in the higher section, where the horizontal lines are so close to one another as almost to suggest a single area made up simultaneously of the different colors.

Of note is the center-high area of the composition where we see an interplay between three different squares that overlap each other as if to express a square in the making that changes appearance:

Diagram D1: One slightly vertical square consists of four red lines;

Diagram D2: one slightly horizontal square is made of three red lines and one yellow line;

Diagram D3: a fully accomplished square consists of the blue line, the red higher horizontal line and the two red vertical lines;

Diagram D4: aanother achieved square proportion can be seen between two red horizontal lines, one yellow line and one blue line.

From the first to the fourth square we see the three primary colors gradually reaching a balanced synthesis between opposites.

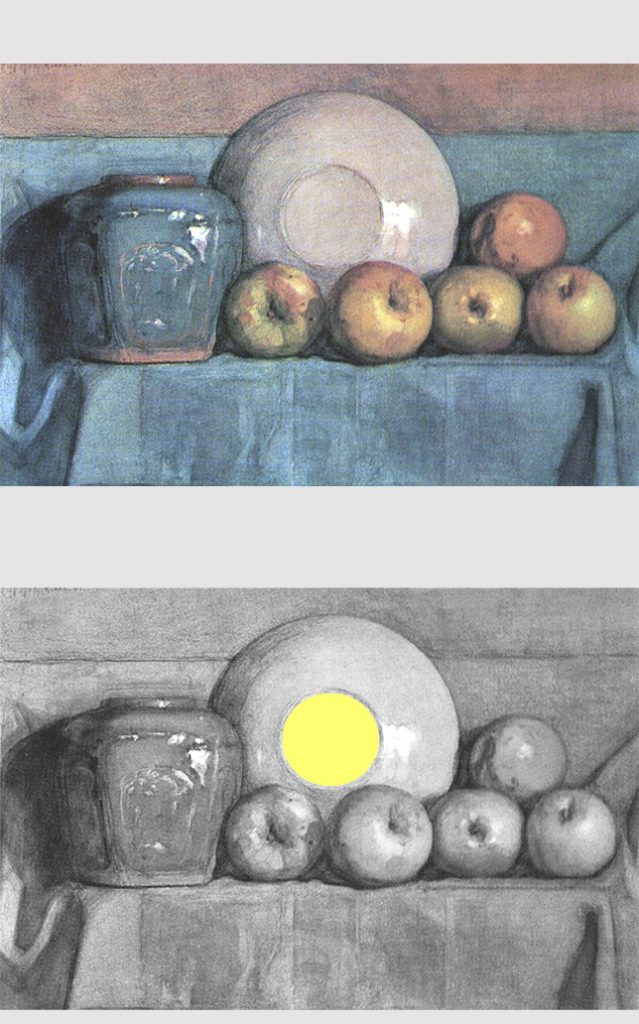

It should be remembered that since 1901 Mondrian often positioned a synthesis in the central area of the composition:

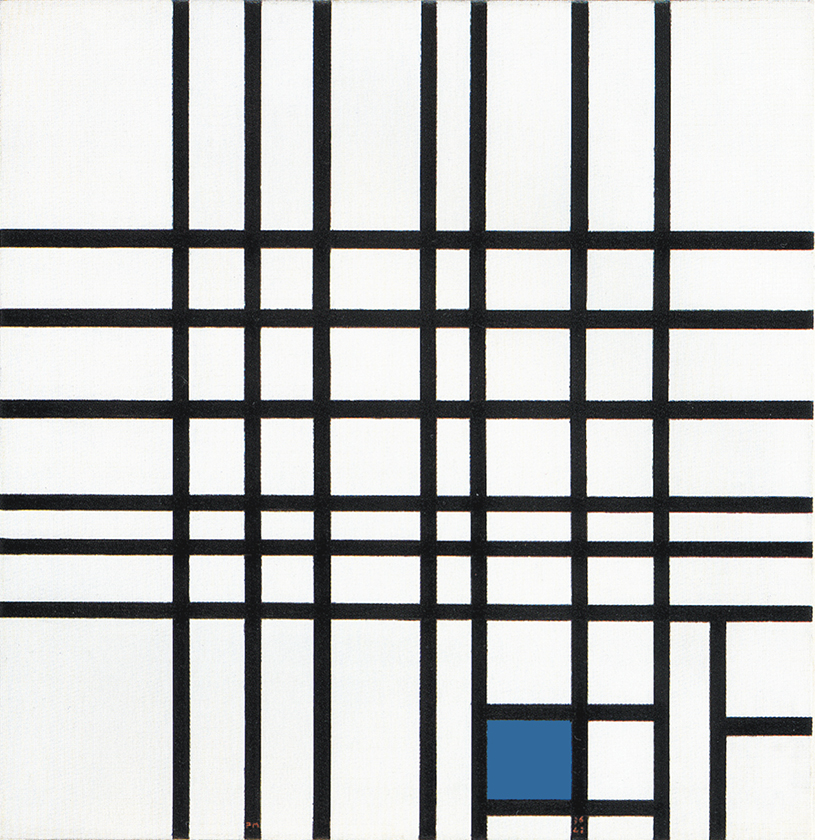

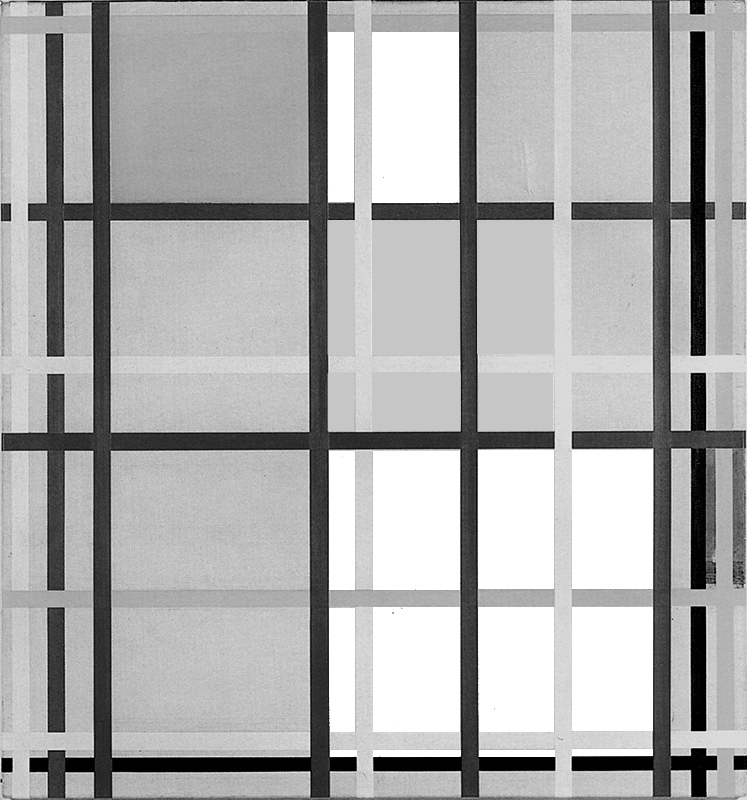

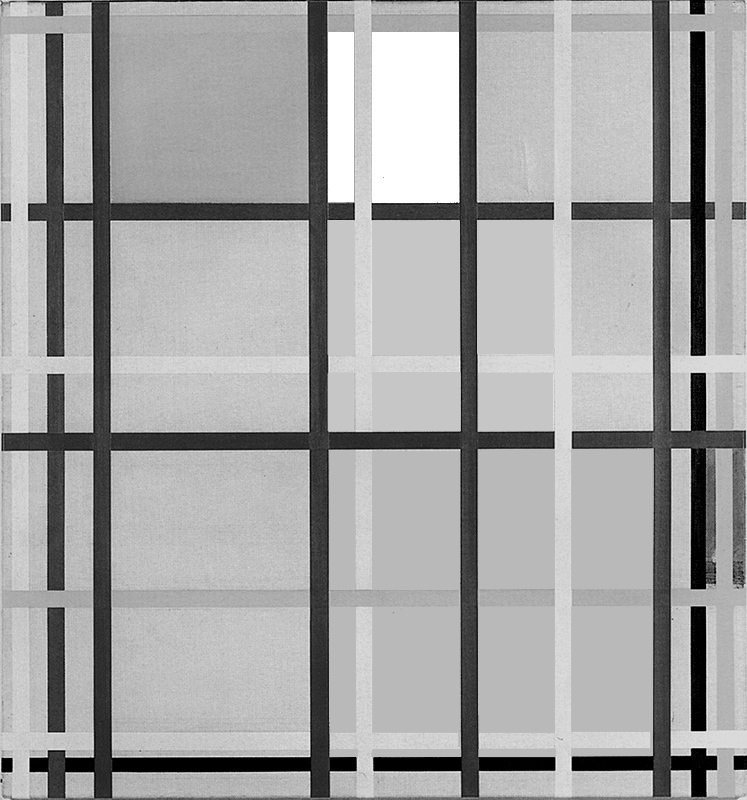

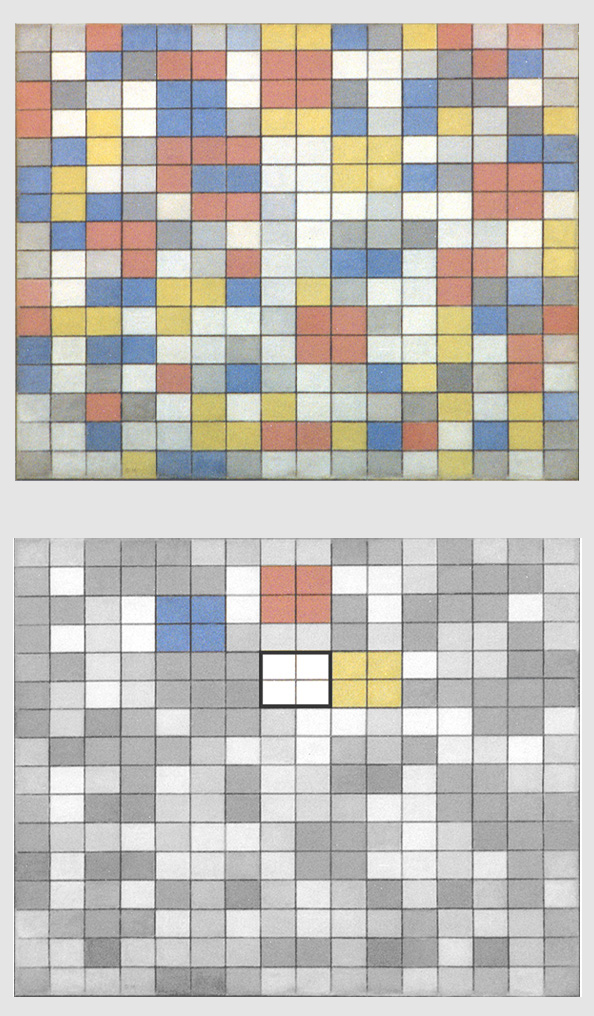

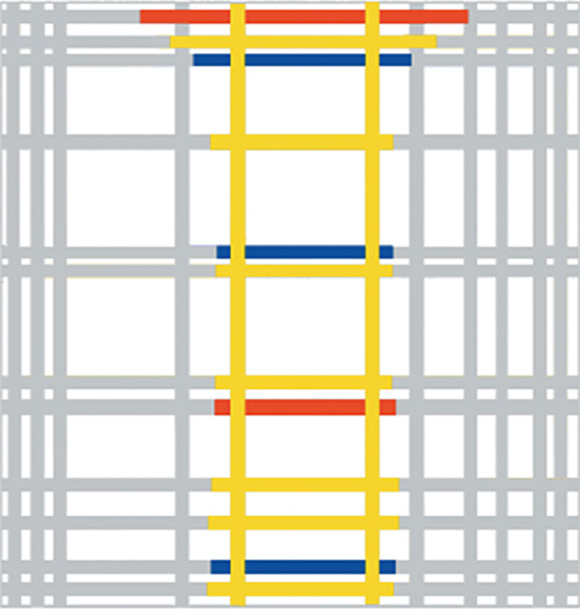

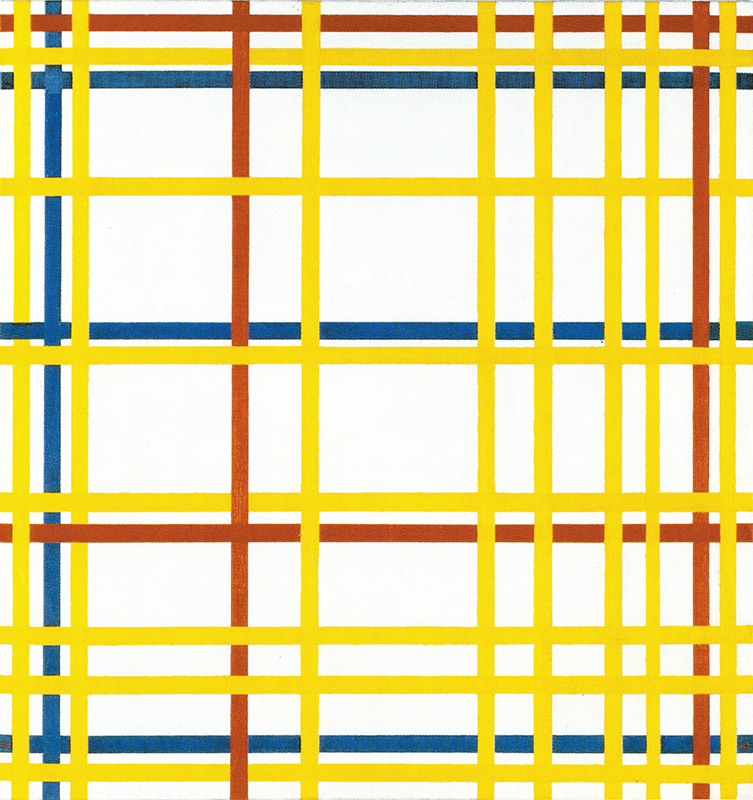

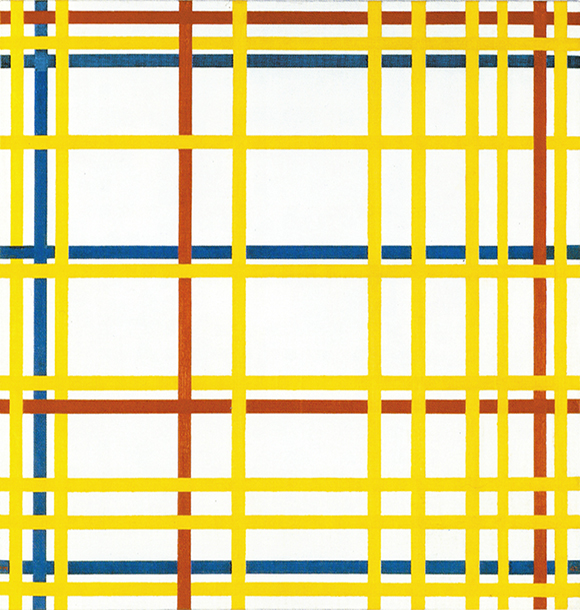

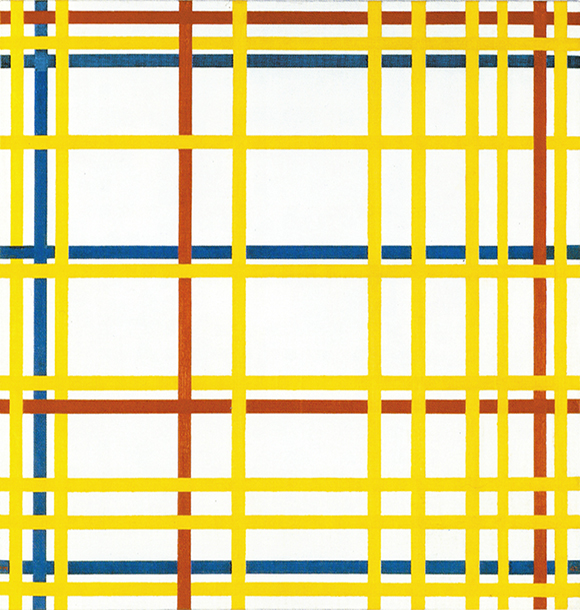

New York City

The opening up to color took definite shape in Fig. 4, where the lines are yellow, red, and blue and there is no black at all. The composition apparently presented nothing but yellow lines and a red plane in its initial state but was later reworked by removing the plane and adding red and blue lines. We see here no fewer than twenty-three lines, fifteen of which are yellow, four red, and four blue:

New York City, 1942,

Oil on Canvas, cm. 114,2 x 119,3

The visual weight of the three colors seems to influence their distribution. Blue and red have greater visual weight and are therefore present in smaller quantities than yellow, which is visually the lightest color (the closest to white). A larger quantity of yellow is needed to compensate for the greater visibility of red and blue. The painter seeks to redress the qualitative balance of the colors through quantitative distribution, providing an example of the dynamic and asymmetric conception of equilibrium.

Yellow, red, and blue lines expand and contract space which is maintained in a state of unstable equilibrium between the two opposing directions. There is an alternating predominance of horizontal and vertical together with different combinations of colors in the different areas. Horizontal and vertical sometimes attain equivalence and assume proportions of comparatively greater stability.

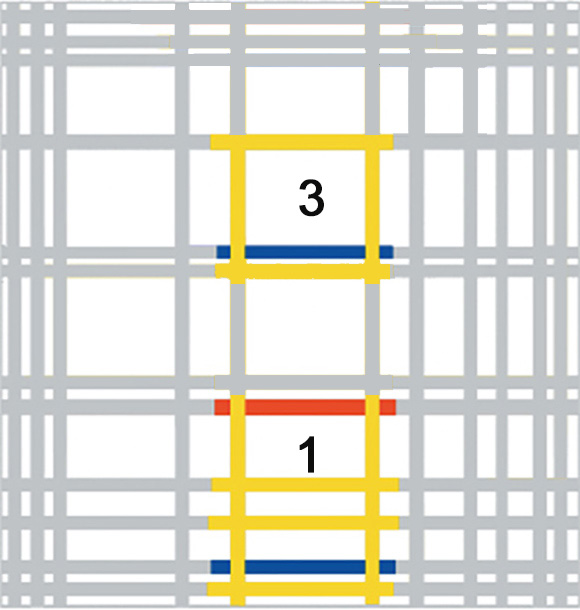

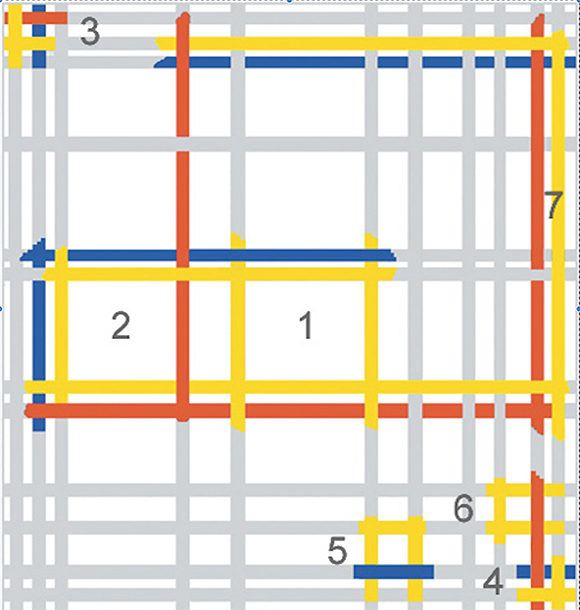

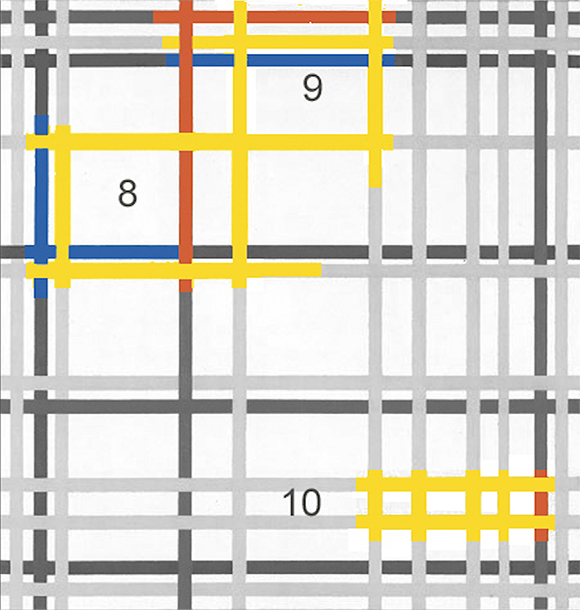

Diagram A presents a series of square proportions numbered from 1 to 7, some of which interpenetrate. Each square differs from the others also in relation to the position assumed within it by lines of the same color. Squares 1 and 2 are similar in terms of form but differ as regards their respective distribution of colors. The same holds for 3 and 4:

Diagram A

Squares 1 and 2 are formed by six or eight lines of different colors and appear to be less sharply defined. Mondrian seems to have been intent above all in square 2 on uniting the three colors so as to express a synthesis of form (horizontal and vertical) and color. The horizontal components of square 2 expand it towards the right into an horizontal rectangle which makes the equivalence of opposites dissolve.

Other squares consist of only two colors (5 and 6). In 6 a completely yellow horizontal rectangle attains equivalence with a red line; the same thing happens in 5 with blue.

Section 1 is a field formed by four yellow lines which present slightly horizontal proportions. The rectangle attains an equivalence of vertical and horizontal if seen in relation to the blue line above or without this but in relation to the red line below. If the yellow rectangle is instead observed in relation to both the blue and the red lines, the slightly horizontal initial proportions become slightly vertical. We thus see a square that oscillates between a slight horizontal predominance (all yellow) and a slight vertical predominance (yellow, red, and blue). The interaction between the two evokes a dynamic square.

New York City, 1942

Diagram B – Section 8 shows a vertical red line which tends to concentrate a rectangle of yellow lines into a square form made of red, blue and yellow, i.e. a balanced unity of form and color. With section 9 we glimpse at a horizontal rectangle made of four yellow lines which hints for a moment to a square proportion higher up by joining with an horizontal red line before being pulled away toward the left by an imposing red vertical line.

Diagram B

It strikes me as important that in the lower right section (10) it is yellow and yellow alone that expresses rectangles with a predominance of one direction or the other. These three forms are made up of lines of the same color. In this case, the variable relations between the opposite directions are wholly homogeneous in chromatic terms and it is form alone that expresses mutation.

As mentioned, the different visual weight of the colors has an influence on the immediacy with which the relationships are perceived. The eye travels along the lines, stops, singles out a certain configuration, and lingers on it, but all around the space is set in motion again with the alternating predominance of the different directions and colors.

Square forms generate and dissolve in a variety of combinations between yellow, red and blue lines. The permanent black and white square unit of the 1920’s has now become dynamic and multiple; not only in terms of form as we have seen in Composition N. 12 with Blue but also in terms of color.

Diagram C shows how a square form develops inside a vertical field that runs through the center of the canvas from the bottom to the top:

Reading up from the bottom, we see a blue and a red line marking out a vertical rectangular field (1) crossed by two horizontal yellow lines that seem to suggest a barely visible square if seen in relation with the lower yellow horizontal line; a square which takes clearer form in 2:

The slight vertical predominance generated in square 2 by the simultaneous presence of the blue and the red produces a counter-reaction higher up and the square now expands horizontally (3) to finally interpenetrate with an horizontal flow of blue, yellow and red lines at the highest part (4).

The finite and balanced dimension of a square form (2) flows back higher up into the infinite dimension of the lines, i.e., either one or the opposite direction only. The equivalence of the Spiritual (Vertical) and the Natural (Horizontal), mind and body and all sort of contradictory drives we experience in our daily life, appears and disappears. The equivalence of opposites is of a dynamic nature. As it is often the case in our lives.

Mutatis mutandis, what we have just seen recalls the compositional development of Pier and Ocean 5 of 1915:

In both compositions a vertical prevalence at the bottom rises and becomes a square that then opens higher up to a horizontal expansion.

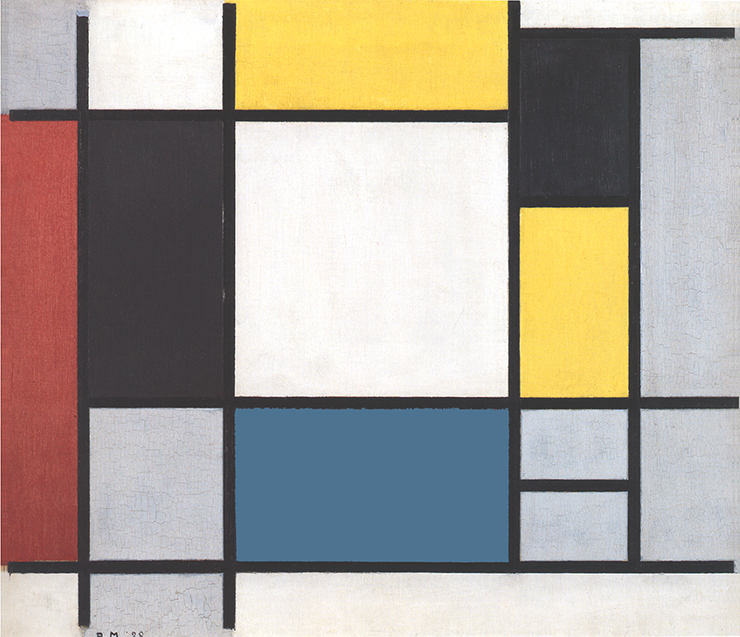

From 1920 to 1942

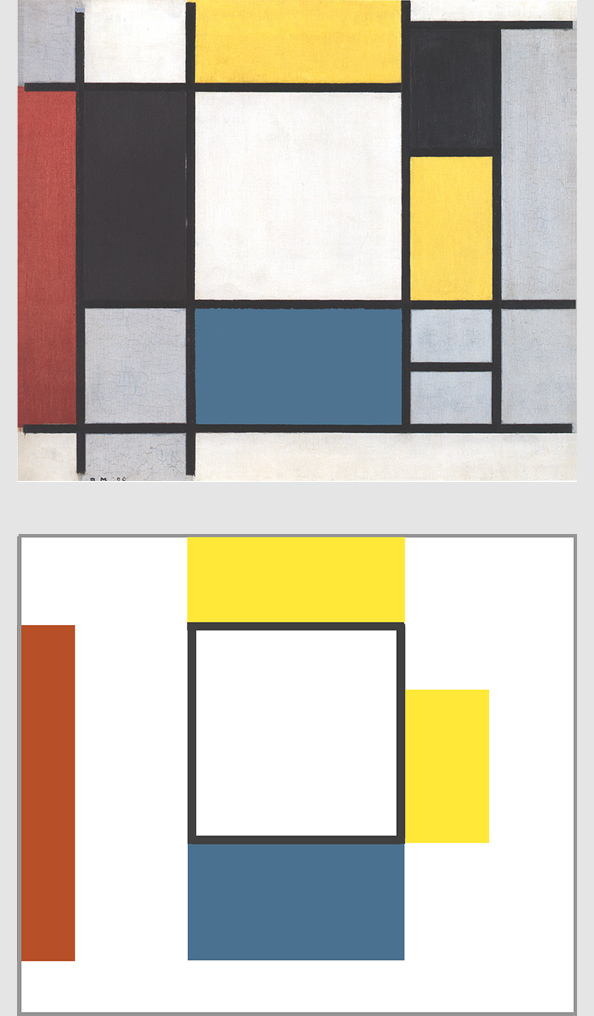

Observe the four compositions below in sequence. In 1920 the colored planes had the function of decentralizing and make dynamic a space dominated by a single large white square formed by black lines:

The square absorbed color over a span of twenty years and multiplied all over the whole surface of the canvas in 1942, changing in terms of position, proportions, and relations between different colors. The single black and white unity of 1920 has undergone interpenetration with manifold space and is now wholly imbued with color and dynamism.

To escape the war, Mondrian had moved from Paris to London in 1938 and by the end of 1940 he arrived in the USA.

The artist lived in New York for three years and four months. This time was divided, more or less equally, between two successive dwellings not far from each other. The first was located at the corner of First Avenue and East 56th Street. The artist had two bedrooms and a kitchen on the fourth floor. The room that served as his studio faced First Avenue, so that the brightly colored rectangles he used to place on the walls could be seen from the street. He often changed their place, like a painting in perpetual evolution.

Mondrian’s second apartment was very similar to the first. It was also on the fourth floor and consisted of a kitchen and two rooms, one of which was used as a studio and the other as a bedroom. The studio is almost empty: a folding easel and two white-painted crates, one of which is used as a palette stand, the other as a color cupboard, that’s all. The walls, also painted white, are strewn with squares of primary colors whose arrangement recalls the compositions with rectangles and without lines of 1917.

The bedroom contains a narrow bed and a frail folding armchair. From the remains of two crates he has made a small wardrobe that sits on the floor. Another crate serves as a seat in front of a small table (just enough to put some papers and an alarm clock). This one is, like all the rest, made of crate debris. This meager equipment has been carefully painted white. The sobriety, the pure lines, give the room a perfect elegance. Here again, the same squares of painted cardboard play on the wall a very sonorous pizzicato of the three primary colors on a uniformly white background.

This is obviously the home of an ascetic who reduces his life to the essential and the essential to the lightest rudiment. But this ascetic is by no means a sorrowful spirit: he loves color and it is through it that the temporal slips into his life. He is an ascetic artist, an ascetic very sensitive to plastic values, the ascetic of beauty in itself. Mondrian is the first contemplator of a transcendent aesthetic, the first picture maker of the absolute.

Michel Seuphor, Piet Mondrian, Sa Vie, son Oeuvre, 1956

Next page: Neoplasticism – Part 6

back to overview

Copyright 1989 – 2025 Michael (Michele) Sciam All Rights Reserved More