A lasting sense of space-time

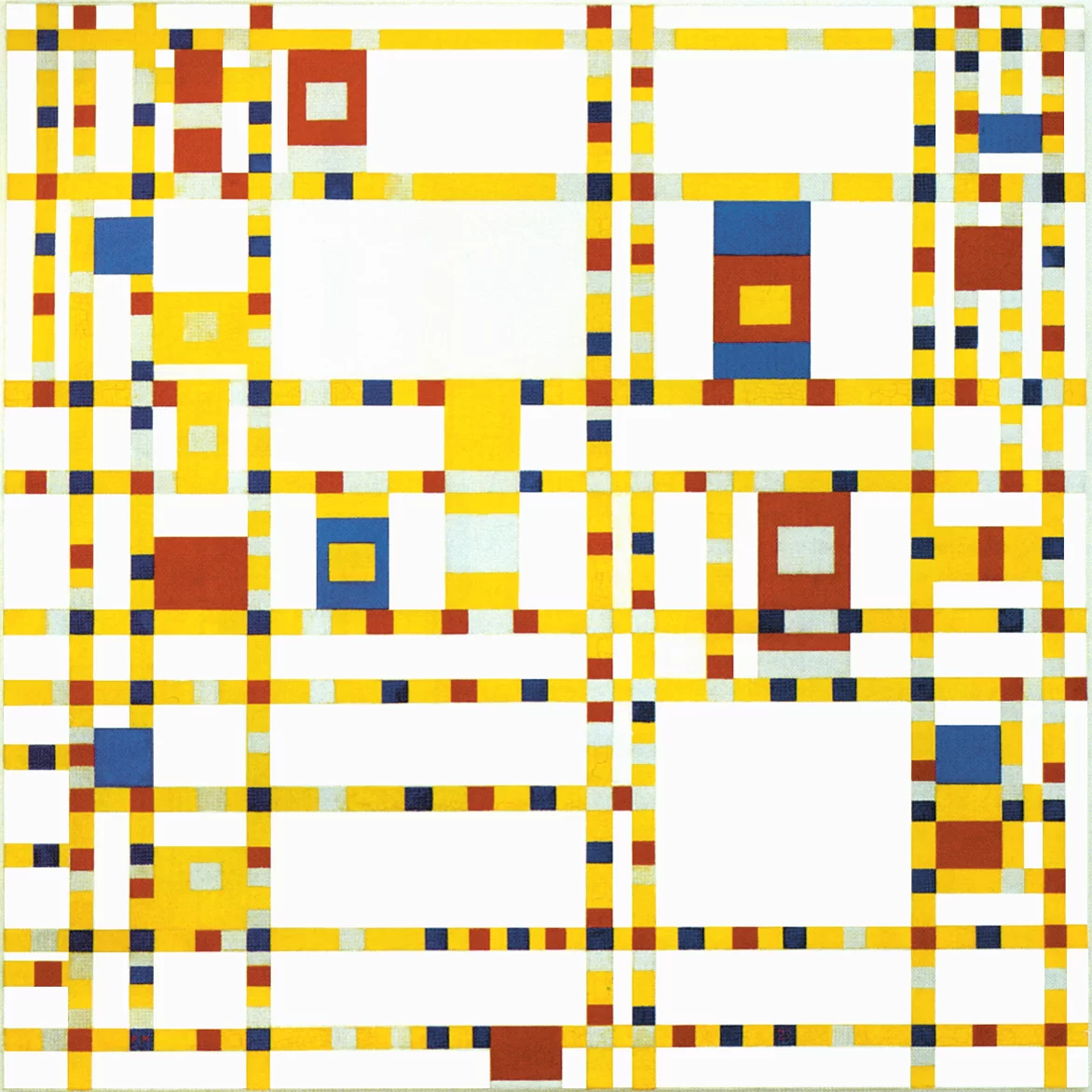

Another aspect of today’s reality interestingly reflected in Piet Mondrian’s Broadway Boogie Woogie and Victory Boogie Woogie is the overcrowded space of metropolitan areas. The space at human height is never the same for more than ten seconds in big cities. Contemporary urban spaces often manifest themselves aggressively and severely test our ability to maintain balance between external stimuli and our inner sense of space-time.

How can we contemplate a landscape in a constant state of change?

Mondrian’s Neoplastic compositions teach us to conceive harmoniously a space in a state of becoming. Just think of how unharmonious the space of our cities is and how frustrating it is for us as we experience every single thing, moment after moment, in a constant whirl of fragments, no longer able to conceive a wholeness.

It would be desirable to have a more durable sense of space-time around us, but this cannot mean bringing today’s world to a halt. We obviously cannot return to the slow rhythms of the human being on foot or horseback, to the more static and monolithic social values connected with the rhythms of life in an agricultural society when the natural landscape changed so slowly as to almost remain static.

More realistically, we can instead work to transform chaotic urban fluxes into more harmonious patterns, harmony being understood as a more balanced relationship between the parts; between the dynamic and variable aspects of physical reality and the sense of greater constancy demanded by consciousness. I have spoken of this repeatedly during my explanation of Mondrian’s paintings and it was, among other things, the point of departure for Cubism: the representation of a dynamic space in a harmonious form.

Yellow, red and blue façades?

In speaking about the relations between Mondrian’s work and urban space, appearance is often confused with substance and somewhat crude examples are put forward. Comparisons are made and analogies discovered with disarming superficiality between the artist’s abstract compositions and the rectilinear façades of modern buildings.

The true link between Mondrian’s vision and urban space lies not in the façades with yellow, red or blue windows but, rather, in the attempt to make the urban scene more homogeneous by transforming the manifold and fragmentary nature of external space into the continuity and duration wished for by consciousness. I shall give just one example for the present.

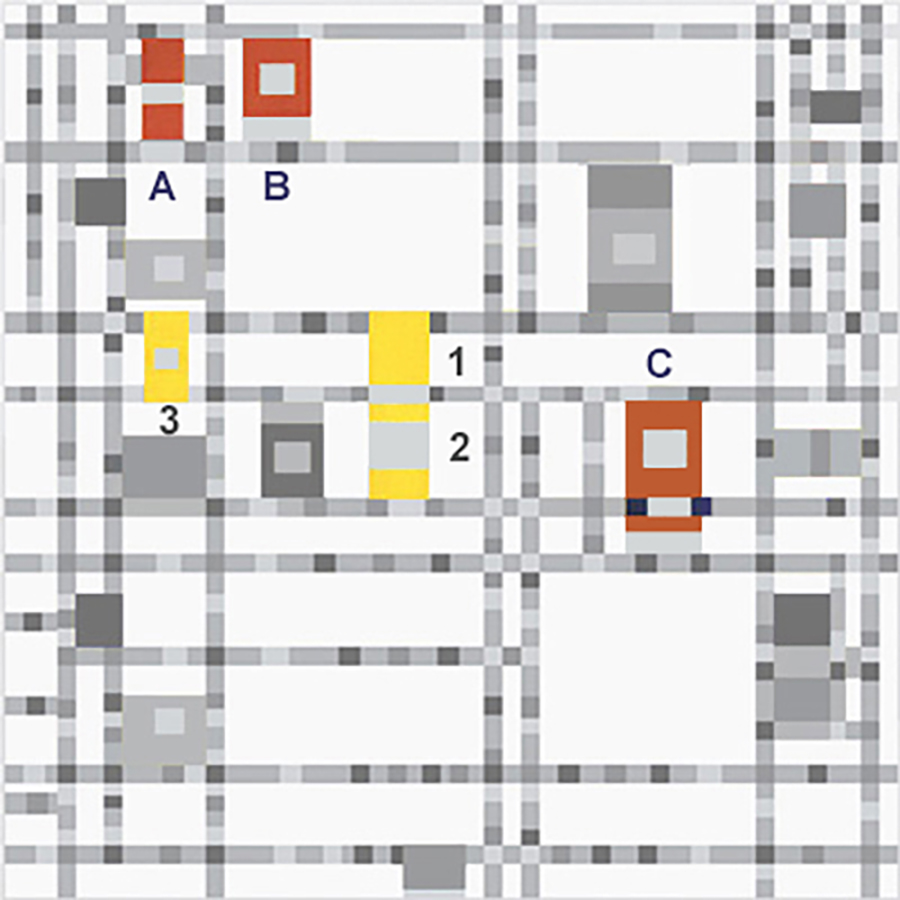

Diagram A: The yellow plane numbered 1, which presents a vertical predominance, comes into contact with a gray segment of a horizontal line.

The contrast between opposing thrusts (vertical vs. horizontal) generates a buildup of tension that is released through motion; the plane moves downward together with the segment, which thus becomes a gray field inside plane 2:

Diagram A: In plane 3 the gray open field of plane 2 is transformed into a gray small square area fully inscribed in a yellow plane. The latter thus seems to represent the conclusion of the sequence initiated with plane 1.

The three planes 1, 2, 3 would thus be three successive moments of a process through which a yellow plane (1) internalizes a gray segment of line (2) that then becomes a small square within a yellow plane (3).

The same also holds for the three red and gray planes A, B, and C, which can be seen by virtue of analogous colors as different instants of one evolving entity. On my reading of the three parts (1, 2, 3 or A, B, C) we have a relational space in which three entities—seen as three different things in a static vision—become one and the same thing viewed in its process of becoming. By adopting a dynamic vision, multiplicity moves towards unity.

This is how BBW should be seen, by contemplating the relational space between the different parts and perceiving the space between them more than the individual things in themselves. Nothing in BBW seems to have value other than in its reciprocal relationship with the other components.

If the space of our cities were constructed in this way, then we really could talk about relations between Neoplastic painting and architecture.

If the multitude of objects that make up an urban agglomeration presented some common elements recurring in different places and moments in such a way as to prompt a guiding thread in our mental space, if every architectural work—all of which being fully entitled to free and original expression—presented visible features shared with others, we would feel that those objects, though different and distant from one another, were constituent parts of a dynamic unity.

I believe that such a vision should guide architects and urban planners in generating continuity among the different objects that make up cities today.

Urban architectural order

What was done in the first half of the 15th century, by introducing order and symmetry into the erratic development of medieval façades, should be done today, albeit bearing in mind that everything has changed in the meantime. A single viewpoint (the vanishing point of Renaissance perspective) has multiplied into a succession of different viewpoints, i.e. into dynamic sequences of viewpoints, and the concept of symmetry (static space) has thus given way to the concept of equivalence (dynamic space), which can confer homogeneity on a quantity and variety of different volumes that are no longer susceptible of standardization in terms of the older spatial coordinates.

Just as every single object was formerly made up of parts gathered together in an organic whole (the façade), every object today should become part of a continuum (urban space), which can thus be conceived again as a living tissue of interconnected parts. In this connection, mutatis mutandis, I am reminded of the splendid Rome of the baroque era.

Learning from history, but without resting on the laurels of the past, we must address the challenges posed by present-day reality with courage, intelligence, and creativity, not least because we have moved beyond the fundamental modules of classic architecture, based for centuries on the proportions of the human body. Today these proportions are no longer crucial even for many human activities, which have come to involve bodily extensions made available by technology.

A dynamic architectural order

I am thinking, for example, of automobiles, which have come by now to constitute an authentic flow of objects in motion that interacts with the static volumes of architecture as literally understood: a stream of self-moving entities available for use as a rhythmic sequence of shapes and colors that could serve as a sort of basic modules (the individual automobiles) of a developing architectural dynamic structure.

Could automobiles become part of a dynamic architectural order? Seen all together, the automobiles that crowd our urban spaces create sequences that appear and disappear within seconds. What is needed is the capacity to evoke harmony in that rapid development of space. One of the great challenges facing artists and architects today is to make space coincide with time. The little time available to us today must be capable of offering us all the mental space we need if our humanity is to manifest itself fully. In my view, the question of values and content is primarily one of measures, proportions and relations, i.e. a question of form (for those who still believe in the difference between form and content).

It is no longer possible to apply the traditional architectural plans and orders in the dynamic context of the modern urban centers. These worked in the static and potentially symmetrical space of the Renaissance and Baroque eras where, among others, the external landscape was always perceived at the same speeds (walking or riding). Today we perceive the urban environment at different speeds that cause the form and duration of architectural volumes to expand and contract within our mental space.

Outer and inner space

It would be necessary to discover an “architectural order” making it possible to reassemble the dynamic and disconnected signals of external space in more durable structures of internal space, an order no longer based solely on external objects but generated in real time between things and us. This would entail education in a new mental space. I regard the Neoplastic vision as constituting an excellent gymnasium for training the mind and spirit in this direction.

One interesting architectural example that not only moves beyond human proportions but also seems to evoke new ones more in keeping with the spirit of the time is the Citicorp Building on Lexington Avenue and 53rd Street in Manhattan, which I have no intention of examining at length here. Work in this direction is also being carried out in Berlin with very interesting results. Rome is instead content to settle for the masterpieces produced by past generations. In Italy the past often becomes a good excuse for doing nothing in the present.

In speaking of phenomena as complex as cities, it is necessary to take variety as a common factor, to translate individual imagination, freedom of enterprise, and plurality of intent in terms of architecture and urban planning without losing sight of the overall context. The question of the relationship between change and constancy, multiplicity and unity I have often called upon during my explanations of Piet Mondrian’s paintings, then becomes an economic, political, and social issue.

The continuum evoked by Mondrian, in which each thing loses its particular nature to become part of a context of relations, presupposes a more highly evolved social and economic system than we have at present. So-called postmodern architecture has instead clumsily reintroduced symmetry, restoring the central role of the object and thereby preventing a dynamic vision of greater breadth. What a friend in Berlin used to call “post-mortem” architecture has in fact proved to be the plastic expression of a conception that was only apparently innovative but actually conservative all the way through, developed by potentates intent on maintaining their positions and largely unconcerned with the quality of people’s lives in the future. Philip Johnson’s AT&T Building on Madison Avenue in Manhattan is a clear example of this.

It may not be long before others discover new pathways of greater present-day relevance in line with the true ideals of a genuine socialism, a term largely misused in the course of the 20th century. Mondrian put forward a utopian proposal to abolish art and achieve beauty in real life. Art would no longer be necessary once it had proved possible to attain the harmonies evoked by painting concretely among human beings. While a look around shows that this will take a long time yet, there are some positive signs.

A new concept of space

It is our own rhythms of life (far more dynamic than those experienced in the past) that have undermined the foundations of a plastic space based on the single point of observation (the vanishing point of Renaissance perspective). It is the social progress of the last two centuries that has transformed the conception of space as a wholly external a priori reality independent of human action in a new conception of space understood as an open structure in a state of constant transformation depending on the active consciousness of individuals. After Mondrian, space is no longer a purely external phenomenon but the result of the relationship between subject and object, interior and exterior.

Aesthetics and ethics

The new concept of space is rather of a reality that is born, develops, and alters together with the subject. We are therefore talking about a dynamic process, an open and flexible structure that is not only a geometric entity but also depends on mental and cultural coordinates.

The new “vanishing point” that unifies plastic space no longer lies solely in external reality but rather in a dynamic equilibrium between the space of the world out there and the space of consciousness. Aesthetics necessarily involves ethics.

I believe that there is a relationship between the social life of a collectivity and the type of space with which it identifies. It is no coincidence that Nazism, Fascism, and Communism were all fiercely opposed to abstract art. Certain present cultural regimes, the expression of obtuse economic power, confine themselves today, more democratically, to ignoring the revolutionary impetus of true abstract art and dishing up surrogates that are as high-flown as they are insignificant.

back to reflections

Copyright 1989 – 2025 Michael (Michele) Sciam All Rights Reserved More