THE NETHERLANDS 1872 – 1911

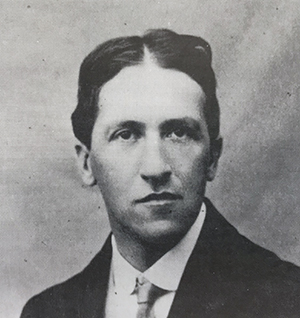

Piet Mondrian was born on 7 March 1872 in Amersfoort, a small town not far from Utrecht, half-way between the Nordsee and the German border. The demon of painting bites Mondrian already at the age of fourteen, as he himself will say.

After primary school, the young Mondrian took two diplomas for teaching drawing and perspective in secondary schools and attended the Royal Academy of Fine Arts while occasionally exhibiting his first works (still lifes). In 1892 Mondrian moved to Amsterdam where he attended the Rijksacademie and became member of an association of painters in Utrecht where he exhibited until 1909. The artist supported himself by making copies, illustrating academic texts and selling some of his work.

In 1897 he joined the Amsterdam society of St. Lucas and Arti et Amicitiae, where he exhibited regularly between 1897 and 1910. During these years Mondrian earned a living with portraits and copies of paintings in the Rijksmuseum and with a variety of commissioned works.

By entering the Prix de Rome contests Mondrian hoped to obtain official recognition as an artist, but his attempts – in 1898 and again in 1901 – were unsuccessful. In 1910 his entry at the Salon d’Automne was rejected. In the same year Mondrian took part with other artists in the foundation of the Moderne Kunstkring whose goal was to mount annual exhibitions of the work of the most progressive artists.

In 1910 Mondrian spends a period in Domburg where he focuses on certain recurring themes (dunes, the sea, a lighthouse, a church steeple) that will be the starting point of the process of evolution towards abstract work.

PARIS 1912 – 1938

In January 1912 Mondrian moved to Paris where he exhibited at various editions of the Salon des Indépendants. He begins his cubist phase. He exhibits his first cubist canvases in Amsterdam, selling some of them. Exhibits in Berlin and Zurich as he continues in the developments of the Cubist phase. Writes first short essays on art. In 1914 he holds his first solo exhibition in The Hague.

At the outbreak of World War I, Mondrian is in Holland where he will remain for the next four years.

The artist helps himself financially by making copies. He meets Theo Van Doesburg and Bart Van der Leck; with the former he would have intense and sometimes contrasting intellectual relations; from the latter he would say he received profitable stimuli for the development of his pictorial work.

In October 1915, Theo van Doesburg published an article in a small Dutch newspaper in which he spoke intelligently and comprehensively about the paintings of Piet Mondrian, who was exhibiting with several other painters in the Amsterdam Municipal Museum. This article was the beginning of a friendship from which two years later the magazine De Stijl was born.

When van Doesburg talked to Mondrian about founding an art magazine but Mondrian was initially reluctant. He thought that the times were not ripe, that van Doesburg should be satisfied with a column in a small newspaper and that the spread of new ideas could only go slowly, gradually. Nevertheless, Doesburg’s entrepreneurial spirit won out and in October 1917 the first issue of De Stijl was published.

When Mondrian returned to Paris in February 1919, the magazine De Stijl regularly published monthly sequels to essays written by the artist. Eager to make his ideas known to the French, Mondrian had been writing more than he painted for over three years. He got help for the translation and published in 1920 at his own expense a brochure entitled The Neoplasticism that however did not arouse the hoped for interest also because of a rather clumsy translation. The publication will also be ignored by art critics.

In 1919 the German architect Walter Gropius founded the Bauhaus in the German city of Weimar.

In February 1921 the Galerie de l’Effort Moderne published in French Mondrian’s essay Le Néo-Plasticisme: Principe Général de l’Equivalence Plastique. The artist delivered nine works on consignment to the same gallery, which, after paying him a deposit, demands him back for lack of sales. Mondrian is disheartened. Financial problems induced Mondrian to consider abandoning painting altogether. A friend helps him collecting commission paintings of flowers that allow the artist to earn some money and continue in his real work.

A performance of futuristic music in Paris (1922), introduced by Marinetti and performed by a group playing a mixture of noise and music, led Mondrian to write a series of articles in De Stijl on the application of Neoplastic principles to music. Sometime later Mondrian wrote to van Doesburg that for lack of money he could not buy an “electric” instrument as he would have liked.

In March 1922 Mondrian’s second solo exhibition was held. The exhibition is curated by the Hollandsche Kustenaarskring at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. To help himself financially Mondrian continues to paint flowers on commission.

In 1923 Mondrian met the Belgian writer, poet, painter and art theorist Michel Seuphor who became Mondrian’s colleague and friend.

In the first Mondrian biography (1956) Seuphor writes: “Once he had laid the foundations for the new language called Neoplasticism, Mondrian worked to explore all its possibilities without ever exhausting its potential. How many times, during this long Parisian period, did I have to listen to comments referred to Neoplastic compositions such as “laziness of spirit”, “stupid stubbornness”, “incapacity for renewal” etc.? I used to caricature these kind of remarks by ironically stating that Mondrian did in fact repeatedly paint only one work.”

In 1924 Mondrian writes the essay Down with Traditional Harmony.

In 1925 he meets Enrico Prampolini with whom he will have friendly relations.

In the spring of 1925, the art critic Paul Sanders is in Paris and frequently visits Mondrian in his studio. The painter entertains Sanders by telling him about the great potential of radio and phonographic music reproduction, jazz, and electronic music. Before returning to Amsterdam, Sanders brother asks to purchase a painting by Mondrian to help him financially. On receiving the money, the painter decides that the sum is excessive and sends two works.

Various friends in Holland helped Mondrian to obtain commissions either for copies, watercolors and drawings of flowers which finally enabled him to keep his head above water.

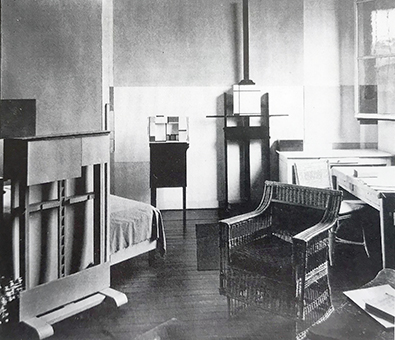

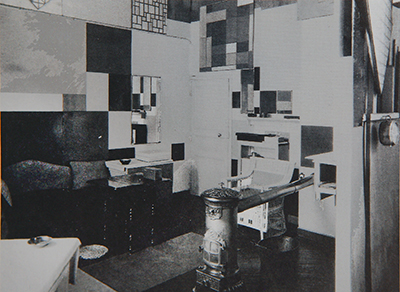

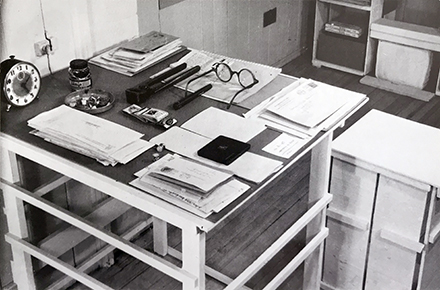

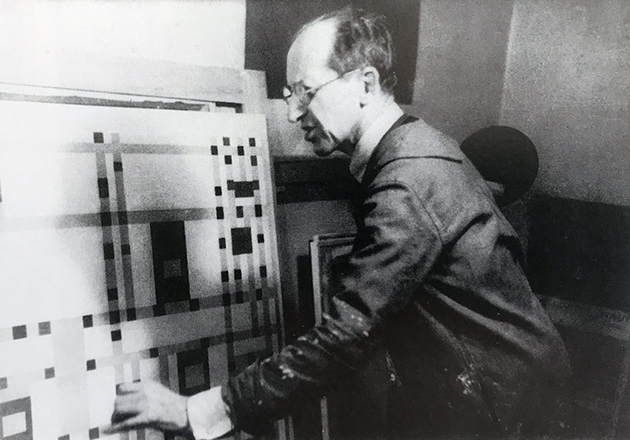

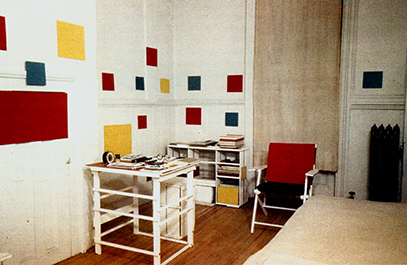

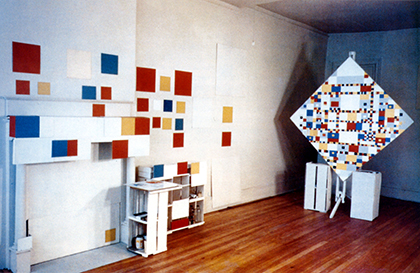

Michel Seuphor tells us that: “Mondrian’s studio at Rue du Depart in Paris was a large, bright room with high ceilings that the artist had irregularly divided up using a large black painted cabinet which was partially covered by an out-of-use easel covered with large red, gray and white cardboard. Another easel was placed against the large black wall which often changed its appearance since Mondrian often exercised his Neoplastic virtuosity on it. The second easel was entirely painted white and was usually only used to show finished paintings. The real place of work was the table.”

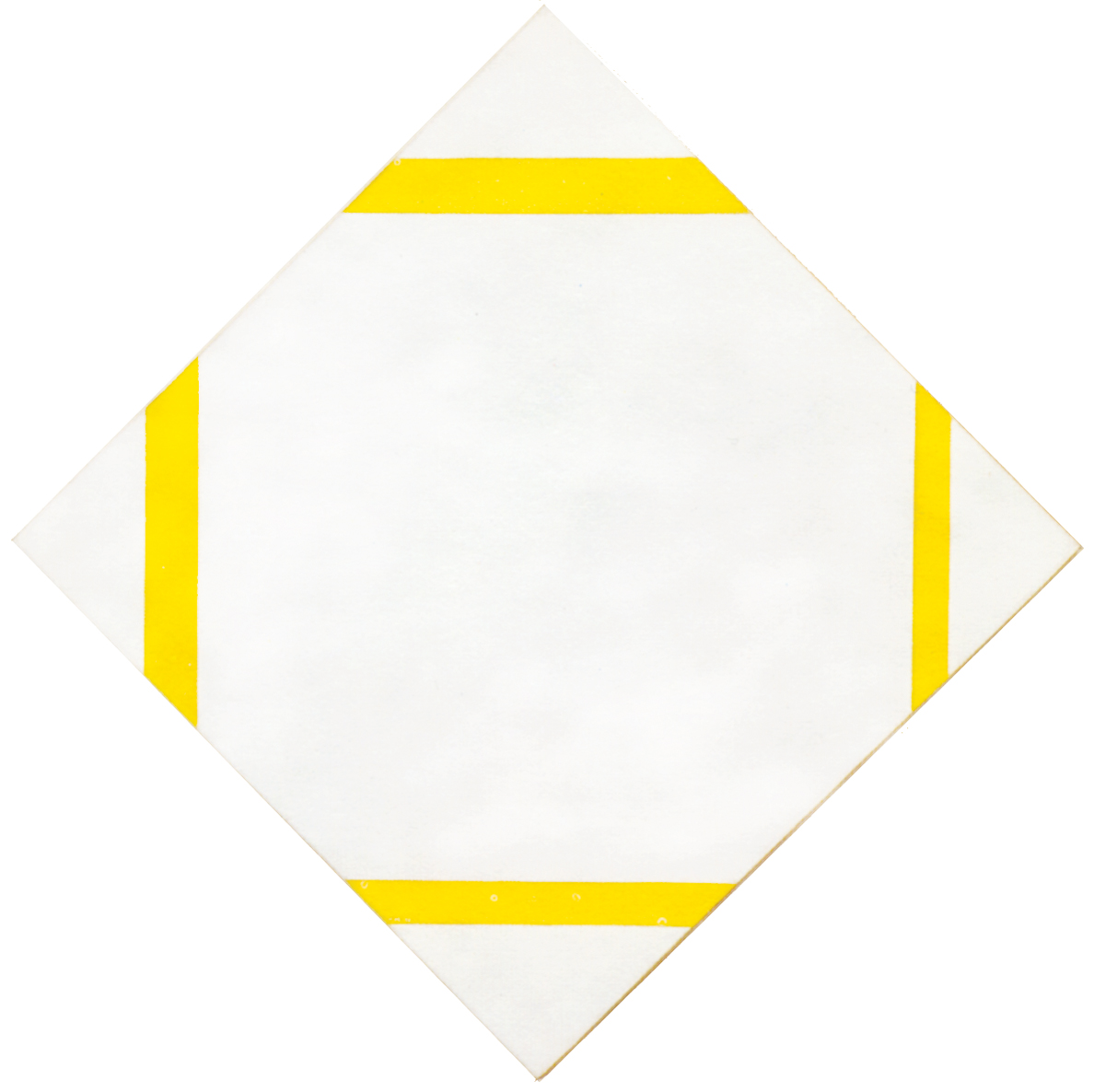

Around 1925 Theo van Doesburg introduced what he called Elementarism in his new works: the composition based on the diagonal. Mondrian, who had regarded van Doesburg as one of the few people with whom he had a close spiritual affinity, was bitterly disappointed by van Doesburg’s failure to understand the dynamic equilibrium of opposites (horizontal and vertical) Mondrian had set forth as a fundamental element of his work and De Stijl. The artistic break with van Doesburg was definitive; on a personal level, however, they resumed contact some time later.

In the same year a painting by Mondrian was included in the exhibition Les Maitres du Cubisme organized by Léonce Rosenberg at his Galerie de l’Effort Moderne in Paris. Rosenberg was unable to sell Mondrian’s work.

Around 1925 Mondrian’s work was becoming increasingly well-known, he even had buyers and admirers in Germany and Switzerland. This enabled him to devote himself entirely to his abstract work without the frustration of having to produce works on commission simply to survive.

In an article published in September 1926 in the newspaper De Telegraaf, the author recounts a visit to Mondrian’s studio where, among other things, he spoke of his passion for Josephine Baker’s dances, declaring that “if the Charleston is banned in Holland, I will have a reason never to return there again”.

Le Neoplasticisme was published as Die Neue Gestaltung in the series of Bauhaus Bücher.

During this period Mondrian was represented in various exhibitions in Germany, France, Holland, the USofA. Writings by Mondrian are published in the Bauhausbücher series. The artist participates with two paintings in the Internationale Kunstausstellung in Vienna. He sells some works in Germany, which allows him a period of economic peace.

To help Mondrian financially, in June 1930 Walter Gropius (founder of the German Bauhaus), Giedeon, Arp, and Moholy-Nagy organized a lottery, the proceeds of which were used to buy a painting by Mondrian for the winner. The drawing took place in Mondrian’s studio in January 1931. Twenty-five people bought a ticket and the prize, a composition from 1930, was won by a German graphic artist.

Mondrian’s contacts with North American art collectors grew. His leading position on the modern movement was recognized by James Johnson Sweeney and by Alfred Barr, director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York City.

In June 1935 Mondrian receives a visit from the director of the New York City MoMA who was preparing an exhibition on Cubism and Abstract Art and will include nine of his works. The exhibition will travel throughout 1937 to other US cities. Works by him was also shown at exhibitions in Stockholm, Brussels and in The Netherlands.

Together with Michel Seuphor, in the early 1930’s Mondrian took part in the group exhibitions of Cercle et Carré and Abstraction et Création.

Kathrine Dreier purchases some works that are sent to New York. American art dealer Sidney Janis visits Mondrian and purchases a work. The following year an American collector purchases a Mondrian canvas for his New York office.

In 1936 American art dealer F. Valentine Dudensing becomes the sales representative for Mondrian and sells two works.

In 1937 Mondrian published an important essay in a book of the English Constructivist group Circle, entitled Plastic Art and Pure Plastic Art. Interest in his work increased steadily in England, but especially in the United States, among both collectors and fellow-artists.

LONDON 1938 1939

The artist leaved Paris which had been occupied by the Nazis and moved to London in September 1938 bringing all his work (some paintings begun in Paris will be later completed in London and New York). In January 1938 he wrote to Holtzman that he had in mind the project for a modern school of aesthetics that, as an alternative to the New Bauhaus in Chicago, would promote a new teaching of art, architecture and industry.

Settled in London, in the month of October of the 1938 Mondrian arranged the shipment of the paintings of greater dimensions, the gramophone, twelve discs and one case of manuscripts.

Hoping to overcome his recurring sense of weakness and frequent respiratory infections, Mondrian adopted a vegetarian and salt-free diet.

Stimulated by the current world situation, in February 1940 Mondrian begun to write an article to make it clear that art makes evident the evil inherent in Nazi and Communist conceptions. The German invasion of the Netherlands on May 10, 1940 and the Dutch surrender five days later deeply upset Mondrian, who was increasingly worried that London would be bombed.The surrender of France on June 22 of that year caused Mondrian to stop working for as long as he remained in London.

The American artist Harry Holtzman, who had visited Mondrian in 1934 in Paris to hear about his theories in person, persuaded Mondrian to move to New York. Following intense nazi bombing raids Mondrian decided to leave London for the USA. Many European artists and intellectuals had preceded him. The artist arrived in New York City on 3 October 1940.

NEW YORK CITY 1940 1944

Mondrian came into contact with the circle of avant-garde artists among whom were others who, like him, had fled burning Europe.

During his four years in New York City, Mondrian concluded a process of evolution in his work that had begun fifty years earlier in the Netherlands and then continued largely in Paris. Many biographies emphasize the new American environment to explain his later works by calling in the lights of Broadway, the Boogie Woogie music, the orthogonal street grid of Manhattan. I believe instead that from the very beginning everything was already present in a nutshell and this I will try to show in the explanation that follows this page.

“By a duly notarized act Mondrian instituted Harry Holtzman his universal legatee. There has been much talk about this in the New York art circle even before Mondrian’s death since the artist had not made a secret of the donation. This will in favor of an American makes the works remain in their homeland of election where they are also the best protected against the decrees – “degenerated art”, “bourgeois formalism” – of the police regimes.” (Seuphor)

Unfortunately we still have curators and directors at Kunstmuseum Den Haag (formerly Gemeentemuseum) who talk about “formalism” when dealing with Mondrian. (see this)

“On Monday, 24 January 1944, Hans Richter, a painter and film-maker, receives a card from Mondrian who, due to a bronchitis, declines an invitation to a cocktail. In point of fact at that time Mondrian was already affected by pneumonia. For two days the artist stayed at home all alone. Nobody would go visit Mondrian without making an appointment as the painter disliked being disturbed while working.

Fritz Glarner heard about Mondrian’s health problems and decided to pay him a visit. He found the artist in very bad conditions, almost unable to speak. Glarner asked Harry Holtzman to call a doctor who certified a very bad pneumonia. Against the artist’s will (Glarner and Holtzman will need one hour to convince Mondrian), the artist is brought to the hospital.

Once in bed in a private room, he is happy and believes he will soon be cured. But the disease had progressed too far. For five days, Mondrian declined little by little. On January 31, his condition is considered hopeless. Glarner and Holtzman kept watch over him all night. Miss von Wiegand came to visit. No one spoke and you could hear the faint gasp of someone who was working to get out of life. At 5 o’clock in the morning of February 1, we learn that everything is over.” (Seuphor)

For a more comprehensive and compelling account of the Dutch master’s life I recommend reading the beautiful biography written by Mondrian’s friend Michel Seuphor, which can now be only found in public libraries (Piet Mondrian, sa Vie, son Oeuvre, Flammarion, Paris, 1956) also available in English language. To complement the information provided by Seuphor I suggest consulting the Catalogue Reasoned compiled by Joost M. Joosten and Robert Welsh.