Please note: If on devices you click on links to images and/or text that do not open if they should, just slightly scroll the screen to re-enable the function. Strange behavior of WordPress.

The Sea and the Pier and Ocean works

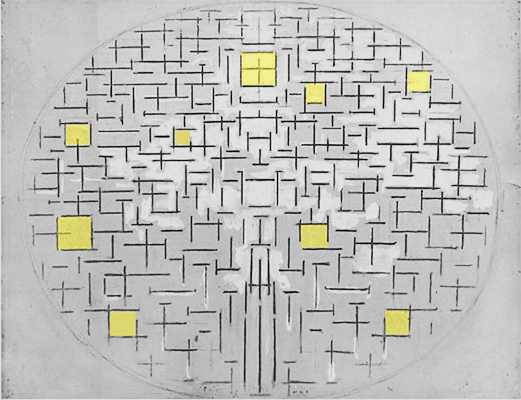

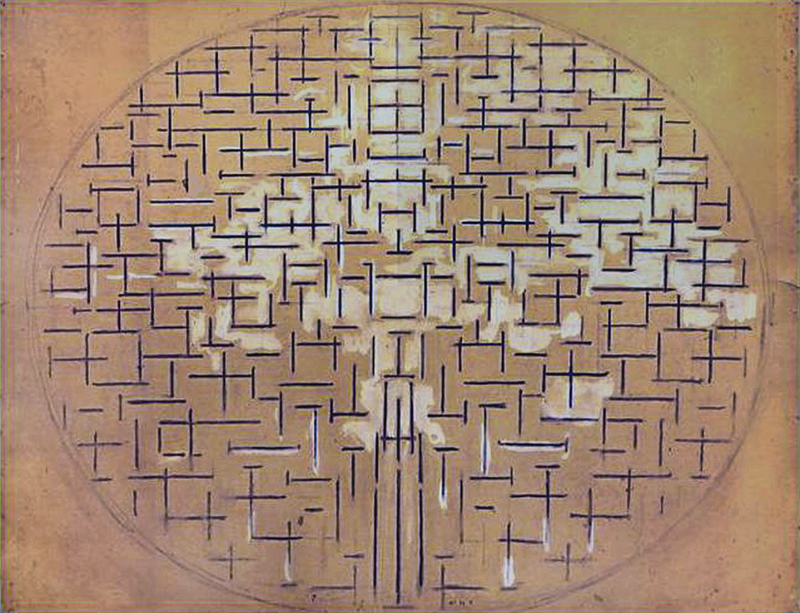

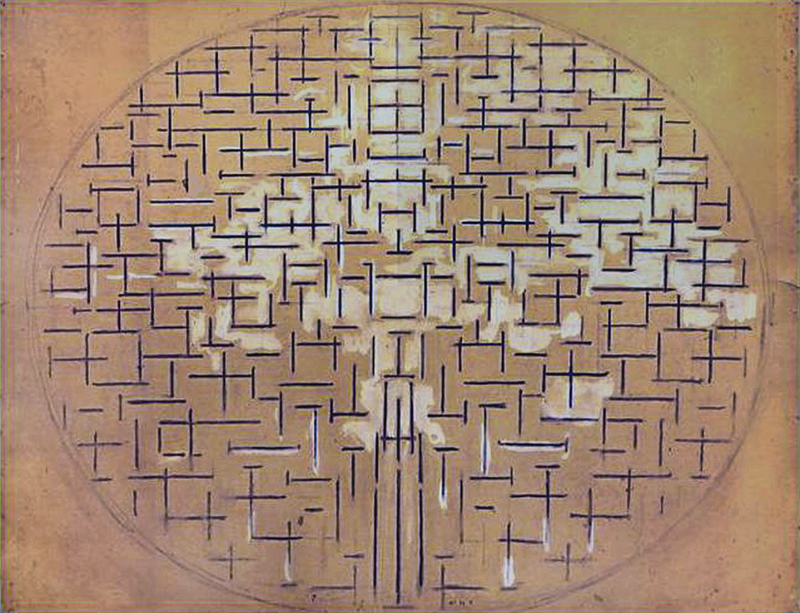

What we have seen so far is confirmed by new paintings Piet Mondrian produces in 1914 and 1915 and in particular by the Pier and Ocean series of works culminating with Pier and Ocean 5. Although painted in a sketchy way, I consider this painting one of Mondrian’s most significant compositions and a revolutionary milestone in western art history.

With Pier and Ocean 5 Mondrian lays out the fundamental principles of a new type of plastic space which constitutes the most effective answer to the questions posed by Impressionism, Expressionism and Cubism.

Charcoal, Ink (?) and Gouache on Paper, cm. 87,9 x 111,7

The artist went to visit his family in the Netherlands in the summer of 1914 and was prevented from returning to Paris by the war, which broke out during his stay. Deprived of the brushes, paints, and canvases left in his studio in Paris, Mondrian began a series of drawings, and gouaches inspired by the sea as well as by a pier jutting out from the seashore into the sea. The latter are therefore also called Pier and Ocean.

The Sea

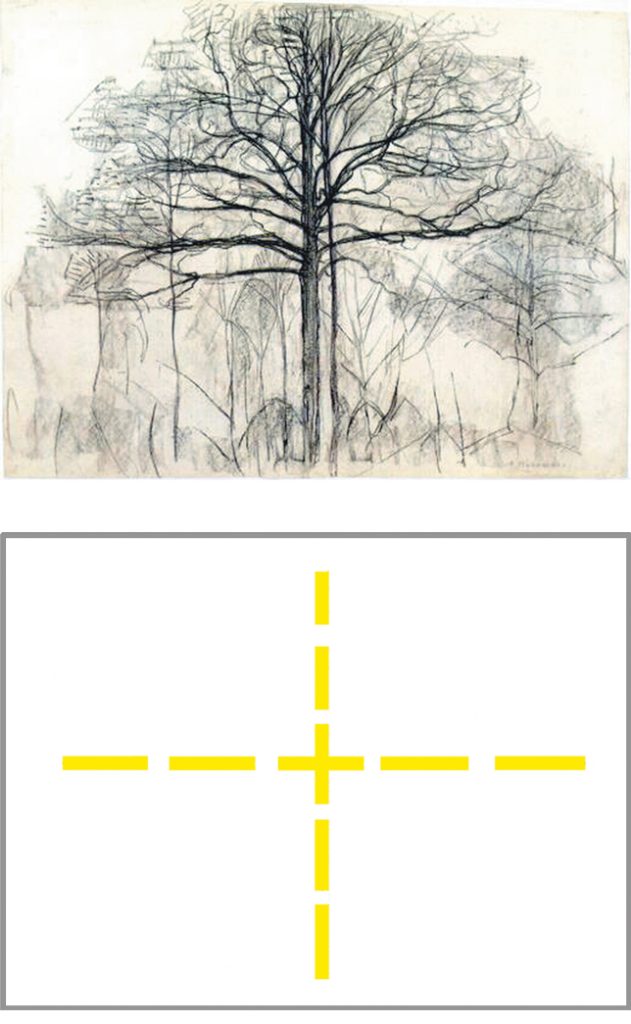

Let us examine two drawings inspired by the sea:

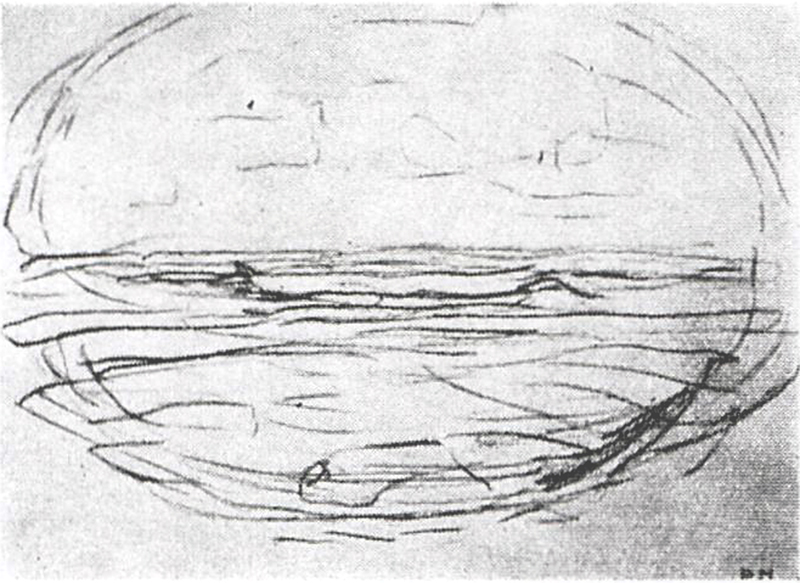

Fig. 1 is a drawing produced in 1914 that recalls the seascapes addressed by the artist four years earlier.

The Sea, Sketchbook 1, Domburg, 1914,

Pencil on Paper, cm. 11,4 x 15,8

The line of the horizon is enclosed in an oval shape. Two points placed in the central area like the foci of an ellipse appear to mark out a segment set slightly below the uninterrupted line of the horizon. This segment evokes a sense of permanence and finite space when compared to the endless line of the horizon as if the boundless space of nature would concentrates for a moment into a finite space. It is therefore a relationship between the infinite natural space and the finite mental space.

I am reminded of previous compositions.

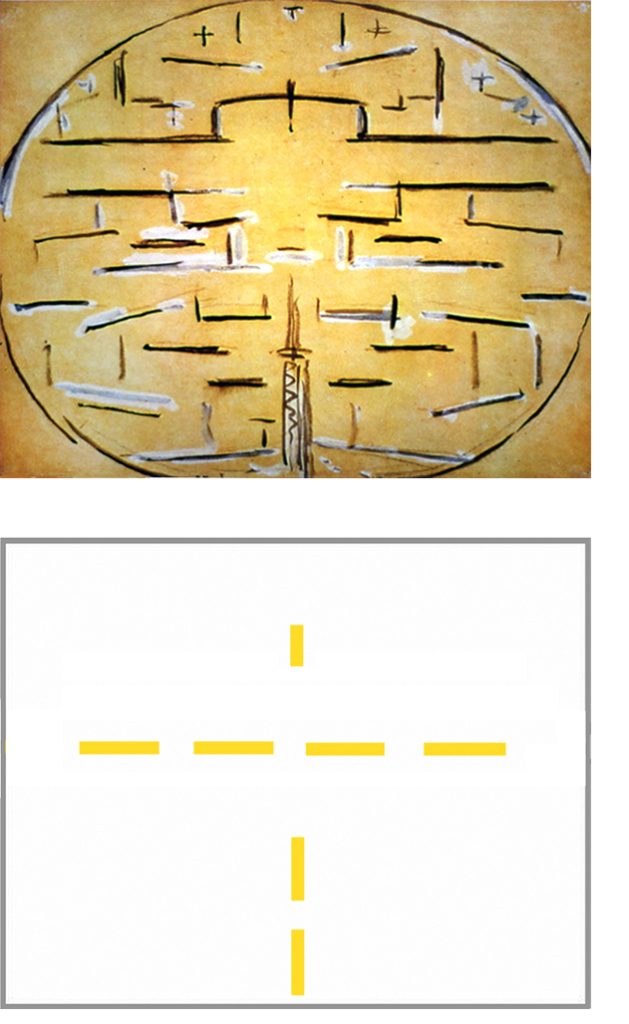

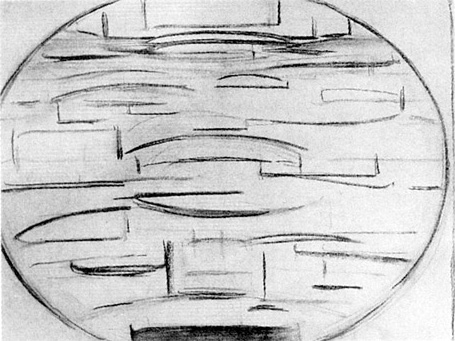

Fig. 2 is a drawing of the sea characterized by primarily horizontal and curvilinear lines with a few faint and isolated vertical elements:

Ocean 2, 1914

Charcoal on Paper, cm. 58,7 x 76,5

The whole is again enclosed within an oval projecting slightly beyond the edges. In the central section we see two juxtaposed curvilinear signs that appear to have developed out of the central segment in Fig. 1.

These signs seem to suggest a small oval inside the oval enclosing the whole. This recalls the concentration of space towards the center already noted in some compositions of 1912. The big oval, acting as an external synthesis both in Fig. 1 and 2, is transformed here into a small oval suggesting an internal synthesis. I recall the search for internal unity Mondrian had strived for around 1913.

Pier and Ocean

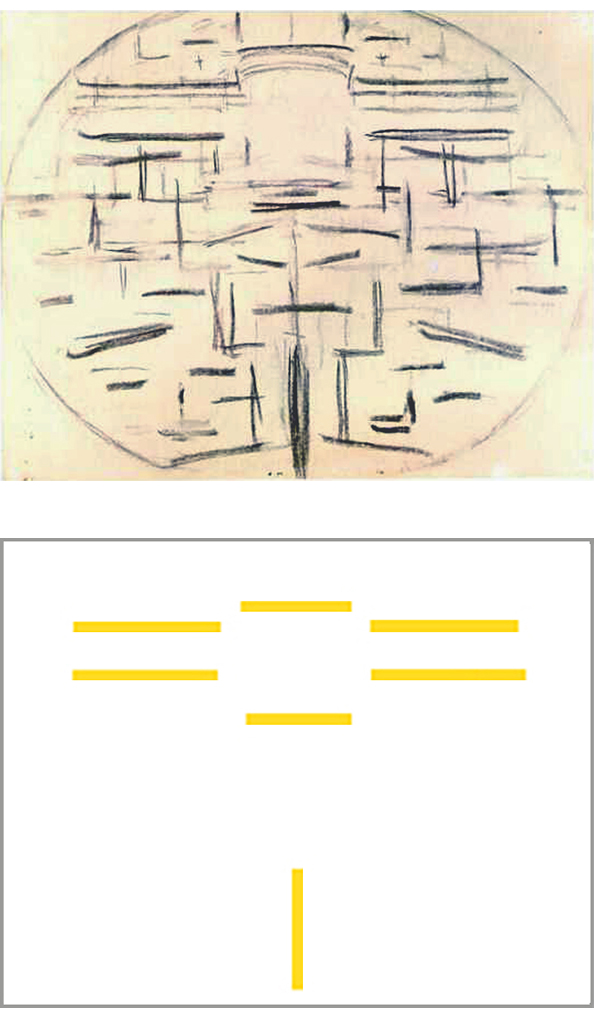

We shall now examine four works belonging to the Pier and Ocean series of works:

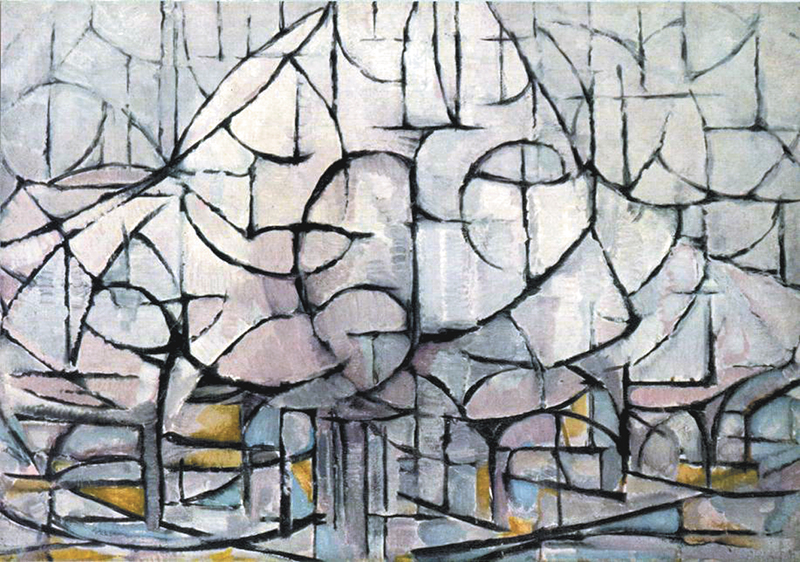

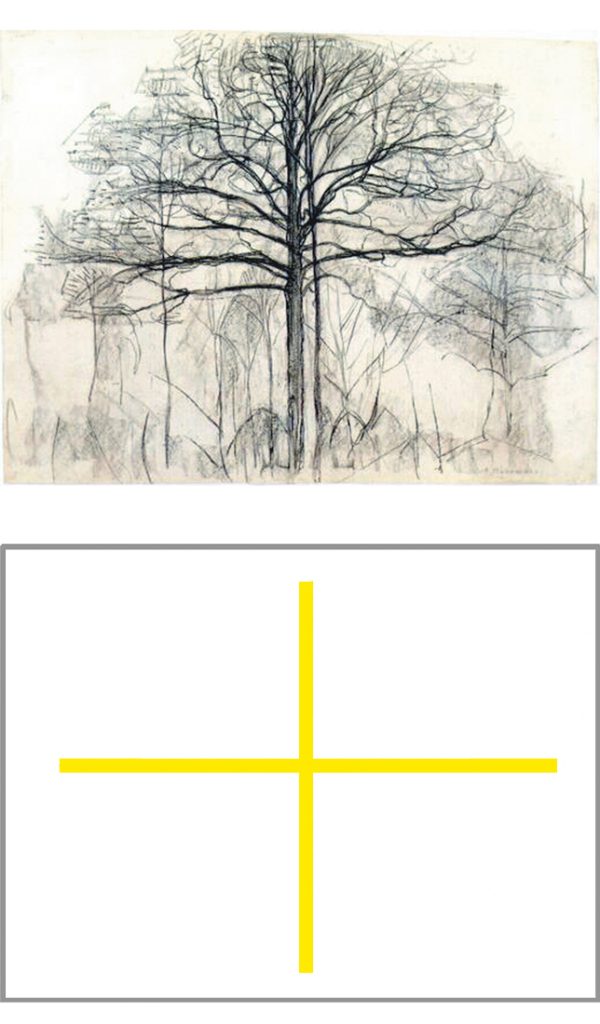

The motif chosen by the painter evokes a structure similar to that of the tree, where the horizontal expansion of the branches corresponds to the horizontal extension of the sea while the vertical structure of the pier is reminiscent of that of the tree trunk:

With respect to the figure of the tree, however, the Cubist subject of the pier immersed in the sea reveals a more dynamic interaction between unitary element (the pier) and manifold element (the sea) than between the mutually static trunk and branches.

Nature and artifice

Here, too, nature (the sea) appears horizontal as in works of the Expressionist period while, from the painter’s point of view, the human artifice (the pier) appears as a vertical like the mills, church towers and lighthouses.

Natural and Spiritual

The artist probably saw the pier structure as a solid element, the symbol of constancy, interpenetrating with the ever-changing flow of the sea. Constancy is invoked by the human mind (the Spiritual for Mondrian) with respect to the manifold and mutable aspect of nature as well as to the changeable course of life (what Mondrian defines as the Natural).

These are issues that go beyond the particular aspect of a certain landscape which, of course, might have stimulated the artist’s inner vision. I therefore believe that the real plastic value of the Pier and Ocean series of works was drawn more from within the artist himself and the body of work he had previously done, more than by the landscape in front of him at that moment.

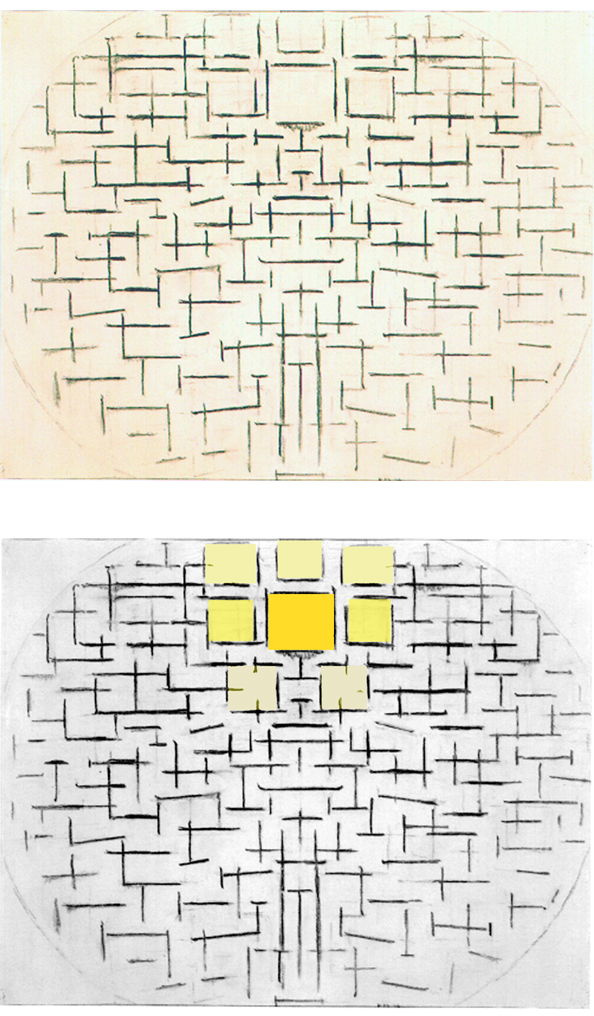

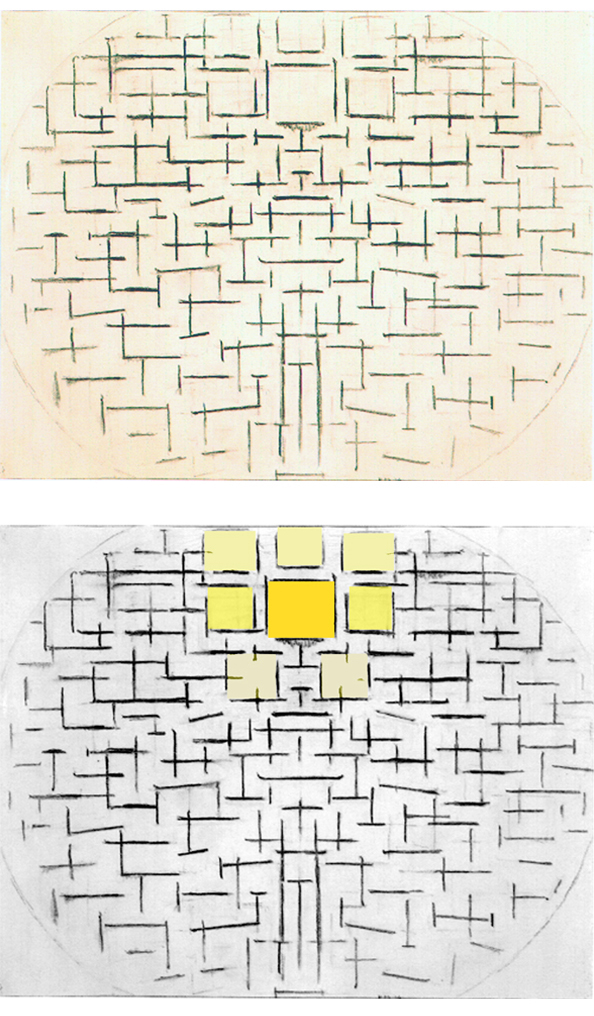

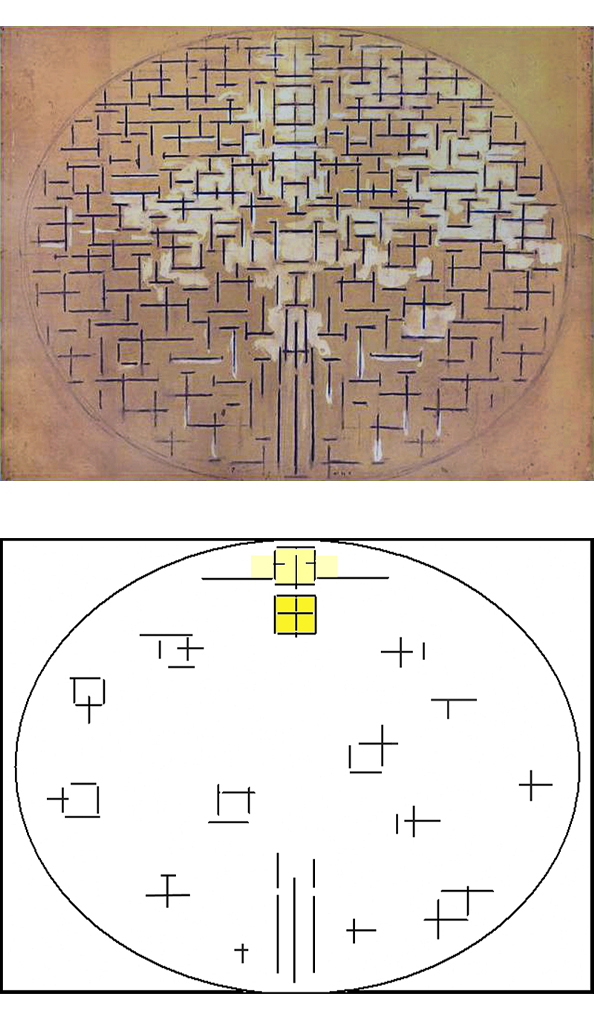

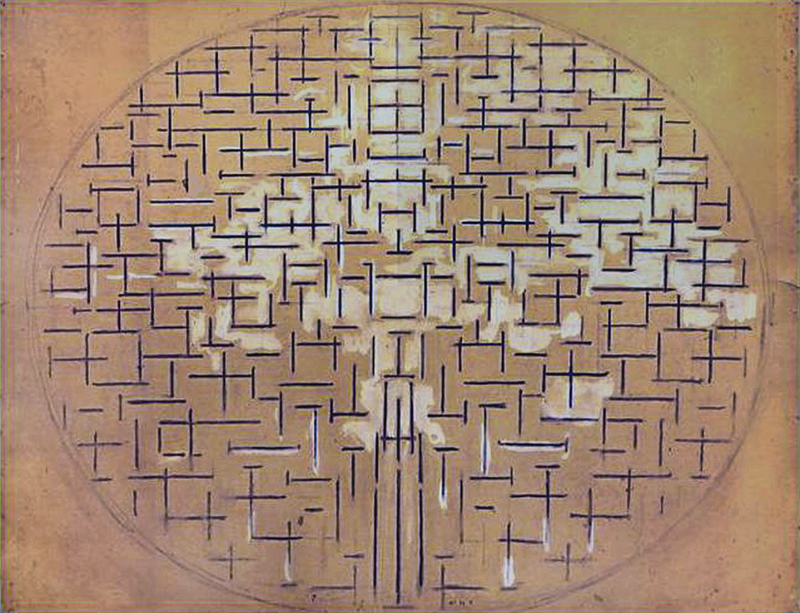

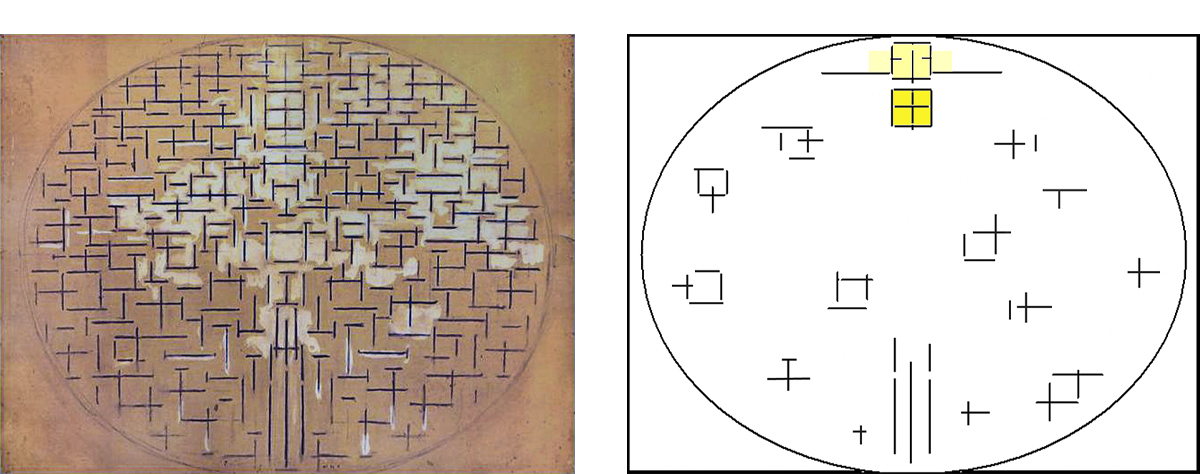

Fig. 3: The interaction between vertical (the finite element represented by the pier) and horizontal (the boundless expanse of the sea) generates in the upper central zone a sort of rectangular field:

Fig. 4: The pier draws the extended line of the sea horizon into a quadrangular area that is then concentrated in the upper section of Fig. 5 to become a set of quadratic shapes with one larger and more defined square in the center:

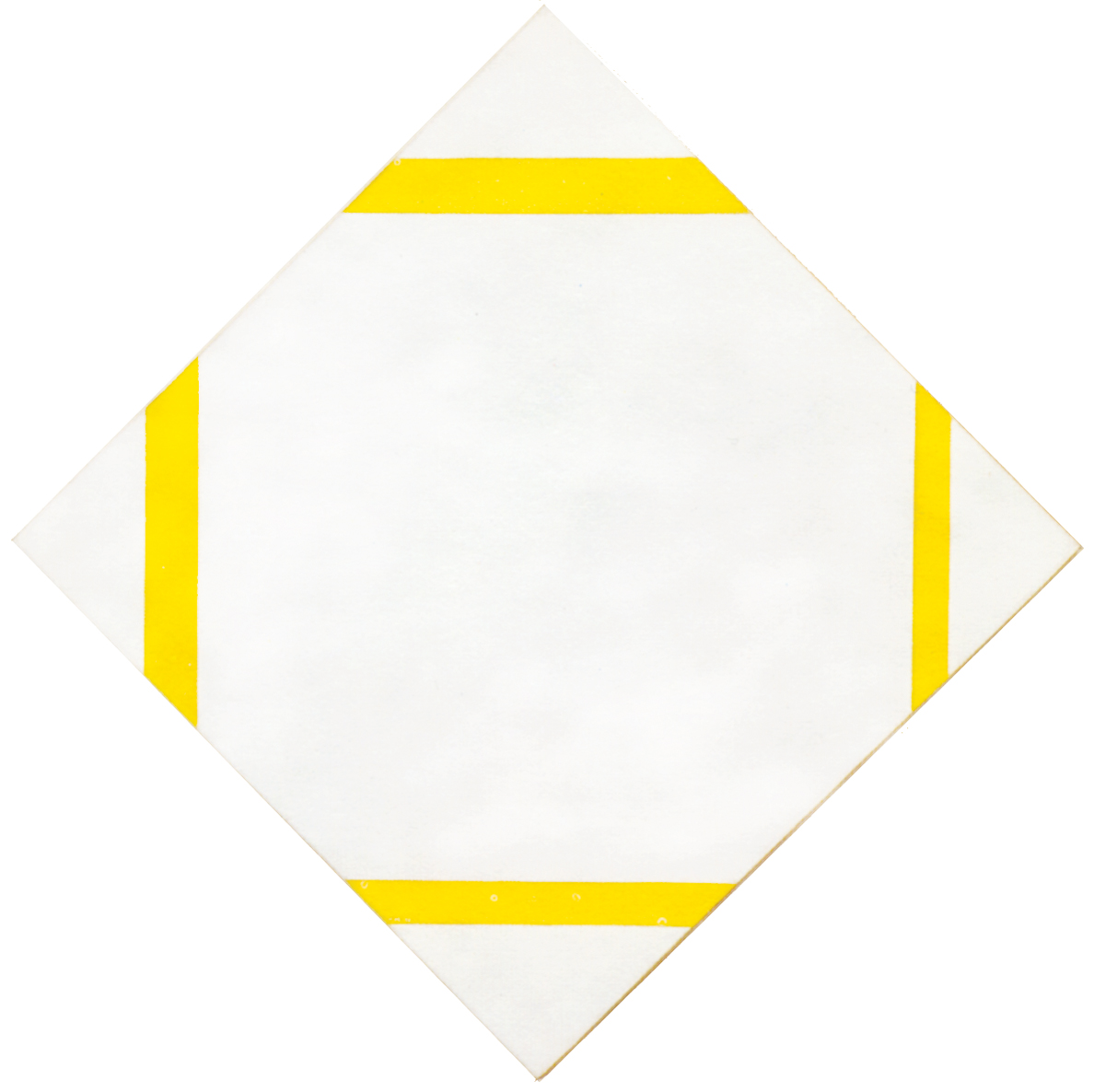

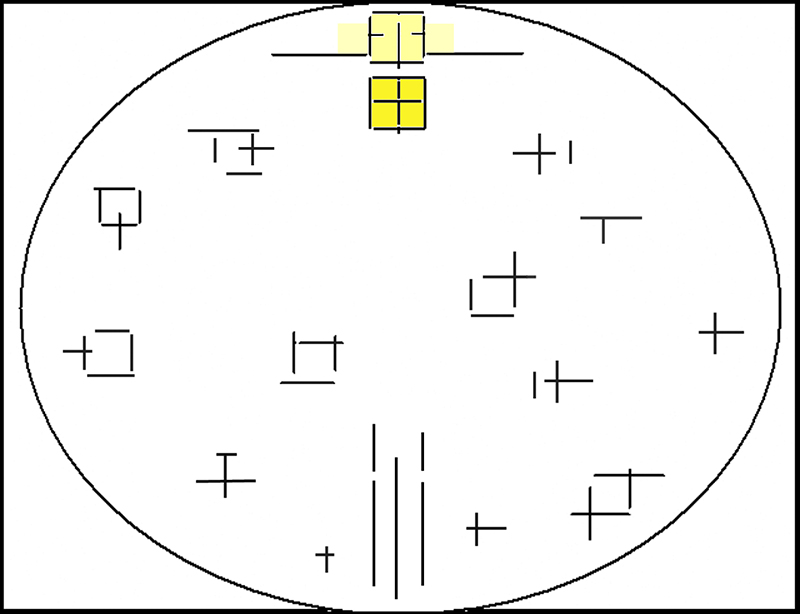

In the latest version of this series of works (Fig. 6), the variegated group of squares we see in Fig. 5 becomes one single square expressing in itself the most balanced relationship between the opposite directions:

The horizontal expansion of the sea (the Natural) and and the motion of concentration exerted by the vertical of the pier (symbol of the Spiritual) achieve a perfect balance within the central square in Fig. 6.

The number of signs, i.e. the degree of spatial multiplicity, gradually increases from Fig. 3 to Fig. 6 and it is only in the latter that all the signs are expressed solely and exclusively through perpendicular relations.

A symmetrical order governing the entire composition can be seen in Fig. 3, 4, 5 and 6. Rising from the bottom upward, the vertical pier (a symbolic projection of the viewer) interacts with the infinite and ever changing natural space (horizontal) giving finally birth to the central square where horizontal and vertical acquire the same value. In that square the boundless and mutable space of the sea (horizontal, i.e. the Natural) concentrates into the finite and constant space of thought (vertical, i.e. the Spiritual). Within that square the Natural and the Spiritual reach a harmonious, balanced relationship.

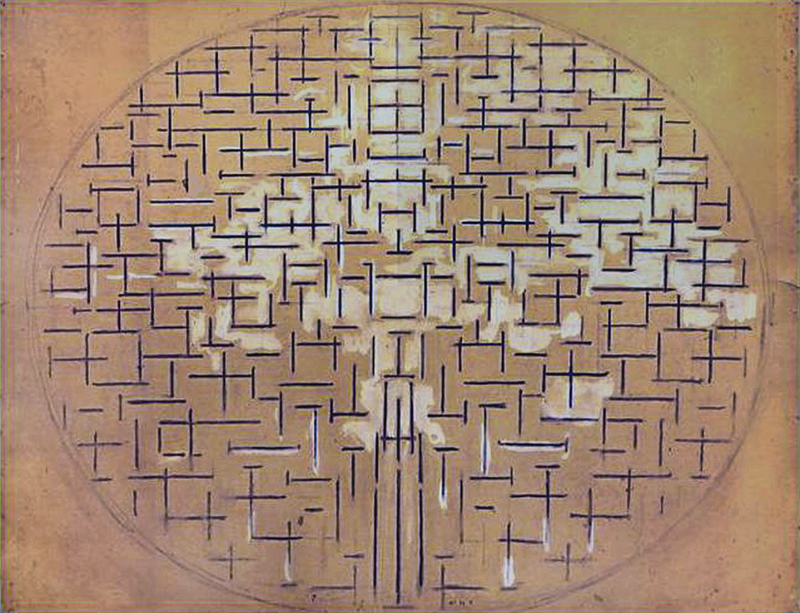

Pier and Ocean 5

Let us now examine in detail Fig. 6 and explain why I consider this composition a revolutionary milestone in western art history.

Pier and Ocean 5 with Diagram, 1915,

Charcoal, Ink (?) and Gouache on Paper,

cm. 87,9 x 111,7

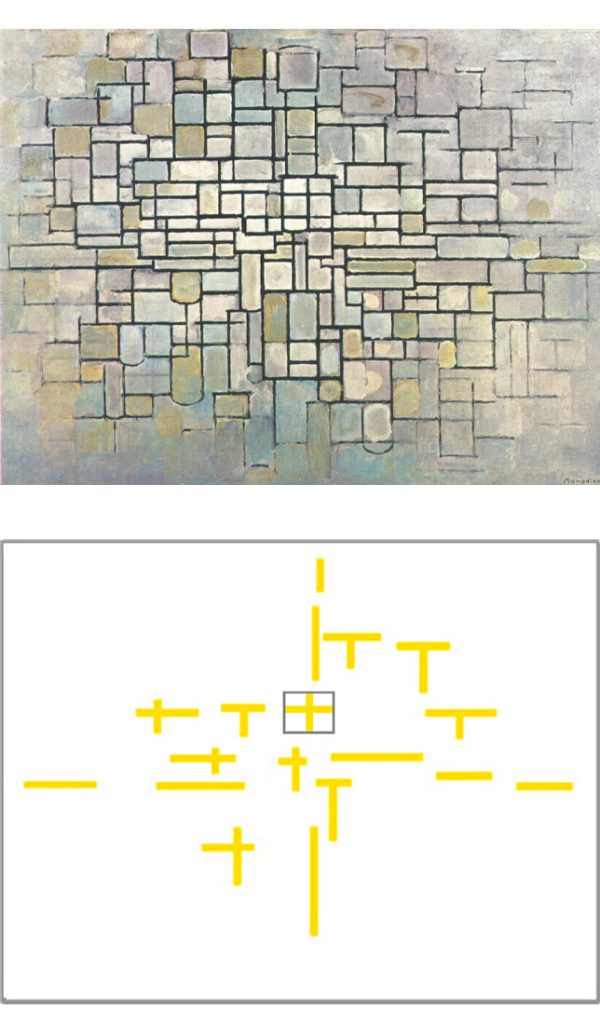

Every sign expresses something different and something changes every instant. Despite its general symmetrical layout, the composition depicts a reality in a state of becoming, the reality contemplated by the Cubist painters.

The duality expressed through the verticals opposed horizontals, which generates the manifold space as a whole, is cancelled out in the square, where horizontal and vertical reach the equivalence, i.e. assume the same value, while remaining opposite. The eye can linger on that point and contemplate in a more stable form what constantly changes in appearance in the surrounding space through alternation of the prevailing direction. The unstable multiplicity of mutable signs is transformed into a more stable and lasting situation in the central square.

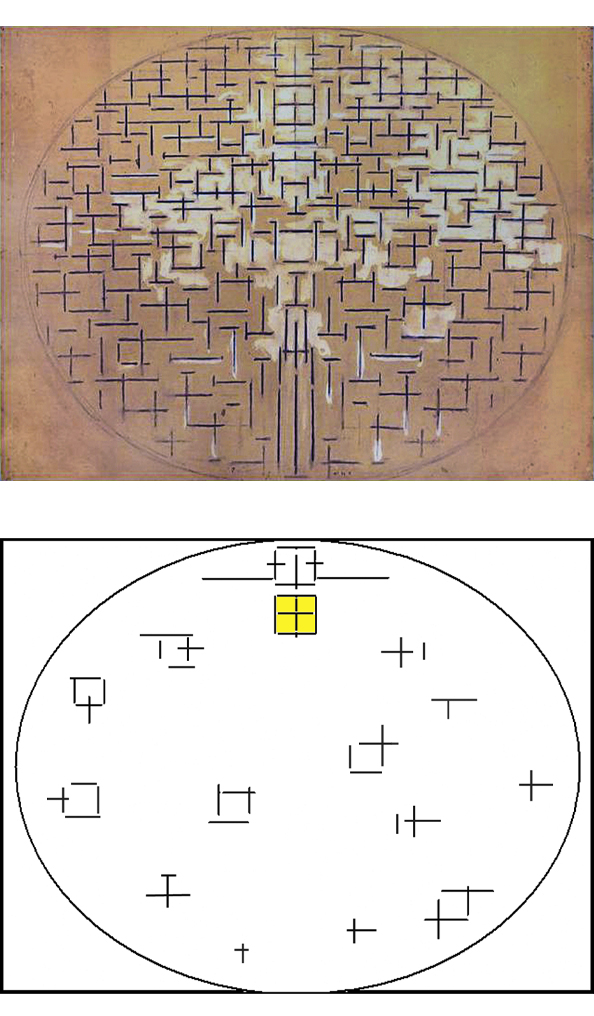

The unity manifested during the first Cubist phase as a curvilinear concentration of space toward the center (Flowering Trees, 1912) and then with a more explicit external oval (Tableau 3, 1913):

becomes an internal oval (Fig. 2) and is then gradually transformed into a square suggesting unity (Fig. 6). An external and absolute unity (Tableau 3) is transformed into an internal and relative unity that now partakes of the manifold space inside which it is born (Fig. 6):

At this regard it is worth remembering what Mondrian wrote:“the compact curved line, which does not express any plastic relationship, has been replaced by straight lines in their mutual perpendicular position which expresses the purest form of relationship“.

The sign of equivalence between opposites is born inside a square and thus suggests an inner space. This square symbolizes the space of consciousness in which the endless imbalances of real life are recomposed for a moment into a balanced ideal synthesis. Examination of Pier and Ocean 5 reveals in fact that other areas of the composition suggest potential squares, which do not, however, attain the balance of the one in the center:

Unlike the central square, the not fully achieved square forms appear unable to hold the dynamic external space and transform it into a more constant and permanent internal equilibrium. The incomplete attempts to internalize external reality evoke the moments in life when something escapes us and we cannot make the rationale of becoming our own. The central square instead expresses one of those rare moments in which we understand (internalize) the fact that everything is connected and that each thing depends on its opposite.

On examining Pier and Ocean 5 in the original, we can see erasures and constant adjustment of the different parts. This creates no disturbance and indeed contributes to the dynamic effect of the whole:

Pier and Ocean 5, 1915

Illusionistic space turns into real space

Same as the vertical trunk of a tree (1912) unified the multifarious horizontal expansion of the branches, a rectangle (1913) and now a square (1915) unify an endless variety of relationships between horizontals and verticals:

The metaphorical unifying function assigned to the trunk of a tree with respect to the multiplicity of branches (1912) is manifested first with a rectangle (1913) and now in clear and direct form with a square that unites horizontal and vertical duality (1915). Duality which generates a multiplicity of different signs all around that square. A so called “realistic” painting, built on the illusion of a third, non existing dimension (1912), turns into a concrete space consisting of the two real dimensions of painting (1915).

Unity of space in itself

The nature of the “landscape” that Mondrian was aiming at now appears evident. Starting from the most immediate reality, the painter no longer stopped at the particular and contingent appearance of a church façade, the sea or a starry sky but extracted the essence of all those fleeting appearances to transform them into an ideal representation of the relationship between observer and all possible landscapes, in other words, between subject and object , that is, between horizontal and vertical:

It is, however, obvious human consciousness cannot contain within itself the totality of the world and will never be able to comprehend reality as a whole (the all-embracing space of the oval). Every synthesis generated by thought is necessarily partial and temporary, and must therefore open up again to the multiform and ever-changing aspect of physical reality and to the changes that life always brings with it. This is what all sensible people do when they call their certainties into question in the light of experience. This is what philosophy has been doing for centuries, as have the arts and above all the experimental sciences.

A second square can be seen in Pier and Ocean 5 above the square that has been already identified:

Inside the second square we see a vertical segment, like the one we have in the square below, while the horizontal segment is now split into two shorter sections that extend beyond the boundary of the square to the right and left. The two small horizontal segments form two cross-shaped marks with the two vertical sides of the square. These two cross-shaped marks tell us that unity is opening up to duality.

The unitary synthesis achieved for an instant in the lower square in the form of an equivalence of horizontal and vertical is broken up into a duality that then flows back toward the variety of different situations marked again by the alternating predominance of one direction or the other. The unity generated with the first square opens up to manifold space with the second square. I see the two squares as one and the same square, that is, the lower one evolving into the upper one.

A dynamic unity

For Mondrian the unitary synthesis is therefore a plastic symbol of the multifarious and controversial space of reality, which can attain measure and a harmonious condition in the space of consciousness before opening up again to the outer world and the unforeseeable evolution of life. This is another reason why modern painting turns abstract: how can you simultaneously represent the outer and inner world if you just look at the external appearance of things, i.e., through the so-called realistic or figurative painting?

The equivalence generated in the square suggests the possibility of establishing balance and harmony between opposites. And this holds both for the subject’s relationship with the object (the external world) and for the subject’s relationship with itself: finding equilibrium between the contradictory drives within oneself, e.g. between the uncontrollable urges of the instincts (evoked by Mondrian by means of the horizontal) and the action of controlling and guiding the instincts performed by the mind or spirit (the vertical).

The spatial development observed in Pier and Ocean 5 tells us that while equilibrium can be attained, it is a dynamic equilibrium that does not necessarily last for long once achieved. The vertical rises, interpenetrates with the horizontal, and produces a balanced unitary synthesis which then opens up again to the horizontal higher up. Multiplicity transforms into unity before reverting to multiplicity. The variable becomes constant and then reverts to the mutable.

The human search for unity (be it the idea of a God or the unifying theories of science) is always counterbalanced by the multifarious and changing aspect of reality. The infinite variety of our world may find a temporary synthesis under the unifying action of the Spiritual (in this case the vertical pier) which then must always necessarily open up again to the Natural (the horizontal sea).

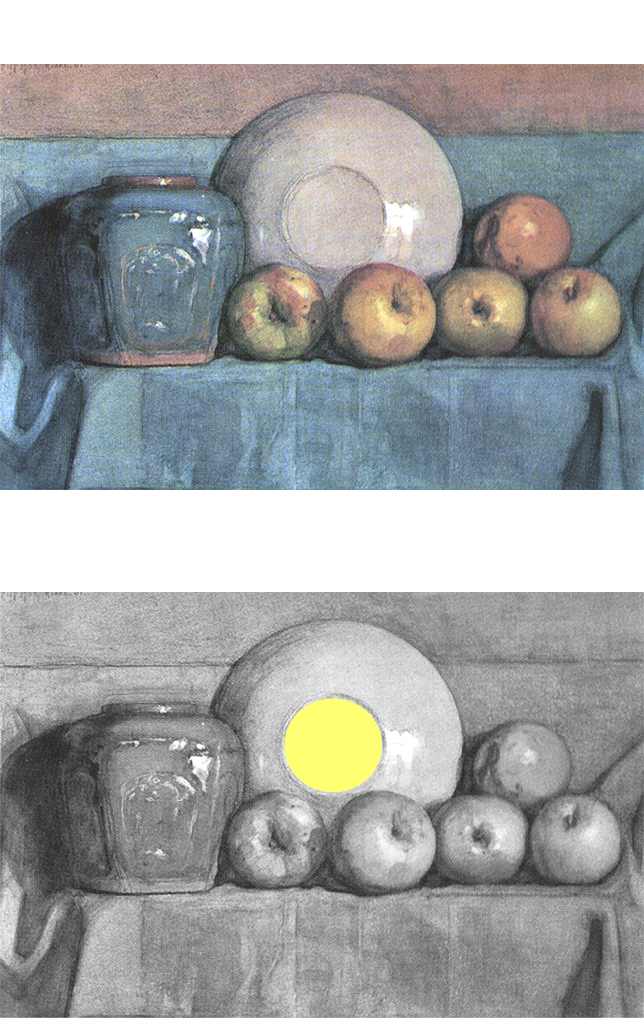

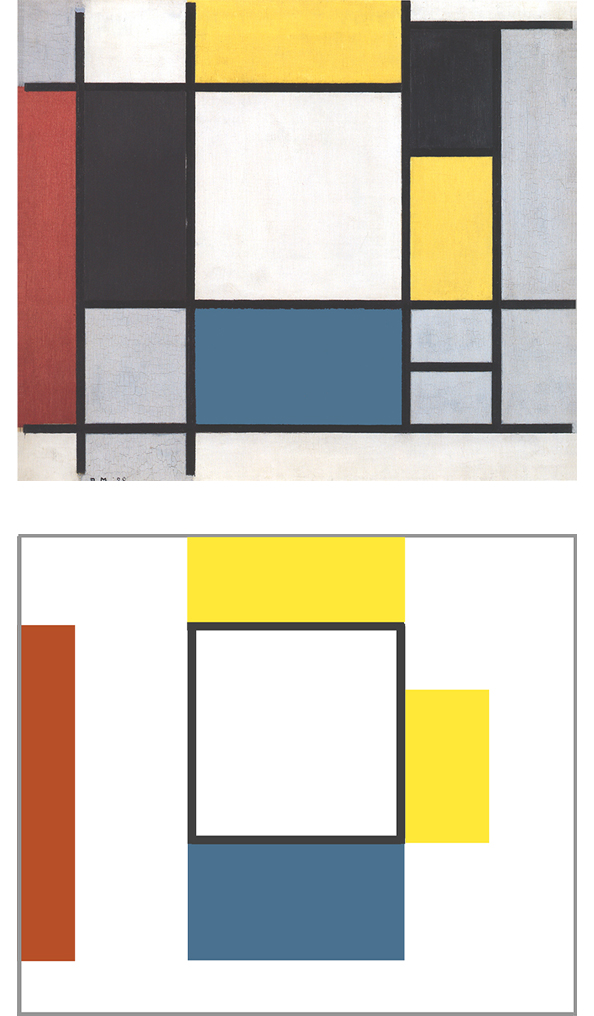

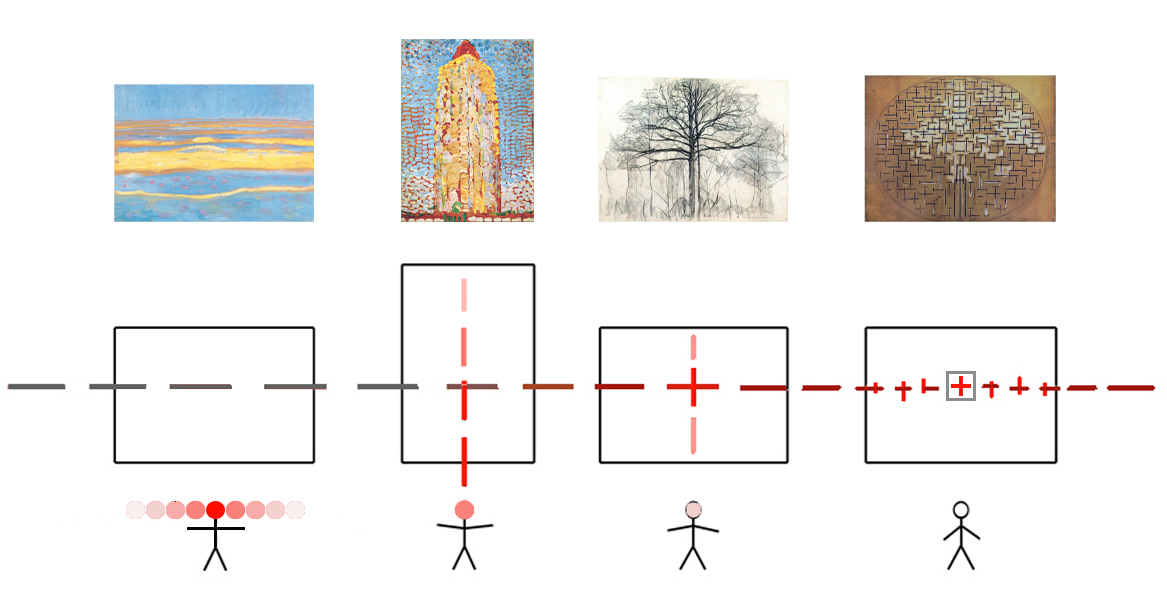

On comparing Pier and Ocean 5 (Fig. IV) with previous works we can see how the unity generated in 1915 is of a dynamic nature and no longer the static unity exemplified by the perfect circle of a plate (Fig. I – Apples, Ginger Pot and Plate on a Ledge), the trunk of a tree (Fig. II – Study of Trees 1) or a central rectangle (Fig. III – Composition II).

The unity that Mondrian strove to express is a temporary synthesis generated momentarily by the consciousness in its changing relationship with the outer and the inner worlds, not something to be attained once and for all. Establishing equilibrium between the manifold appearance of nature or the often conflicting inner impulses on the one hand and the synthesis invoked by the consciousness on the other does not mean attaining fixed points and immutable truths.

The square of Pier and Ocean 5 is not a potentially static and all-inclusive unity like the oval but a dynamic unity intrinsically linked to the manifold space in which it is born and toward which it returns a moment later:

The one becomes multiple and multiplicity reverts to unity. As mentioned, every synthesis generated by thought is necessarily partial and temporary, and must therefore open up again to the multiform and ever-changing aspect of physical reality. Moreover, Mondrian thinks of a unity which is intrinsically multiple and multiplicity which is in truth one because everything is at the same time one and multiple.

To give a concrete example: a tree looks like a small patch of green when seen from a great distance but then grows larger and reveals an increasing number of parts as we draw closer before finally displaying an enormous degree of complexity when we consider the microscopic structure of each individual leaf which becomes a small universe.

The initial green spot (we perceived as one) has become very complexed (multiple); the initial finite reality appears now infinite. If the process is reversed, the tree loses its complexity and reverts to a simple patch of green.

Depending on the positional relationship established in each case with the object observed, every single thing becomes multiple and then multiplicity concentrates again into a unity.

What is the “true” nature and reality of a tree? Does it still make sense to paint a tree from a single viewpoint (the so-called realistic view) and claim that this is reality? How can we paint things that change so quickly today in accordance with the changing positional relationship we establish with them? And how can we define realistic a way of considering the finite outer appearance of things only if every single thing unveils an intrinsic endless reality? How can we simultaneously show the manifold and unitary aspect of each individual thing if not in an abstract form?

The painting under consideration succeeds in expressing the intimate structure of one thing and at the same time of all possible things that appear different at first sight. The immense variety visible in nature is the result of an infinite combination of the same basic elements that Pier and Ocean 5 brings into focus.

Precisely because it is abstract, the painting can suggest the inner complexity of every single thing and at the same time the changing plurality of all things without forgetting that sense of unity invoked by the human spirit.

The above series of paintings inspired by the sea and a pier can be considered a sort of conspectus of Mondrian’s work between 1908 and 1915, as though the Cubist space developed at length in his studio in Paris had finally found an outlet in contact with the Dutch countryside from which it originated. When Mondrian returned to these subjects in 1915, he drew them more from within himself than from the landscape in front of him. He addressed them again in order to tie up some loose ends left in the Cubist canvases painted in Paris. In doing so, he provided a de facto summary of the work carried out between 1912 and 1914.

Objective and subjective unity

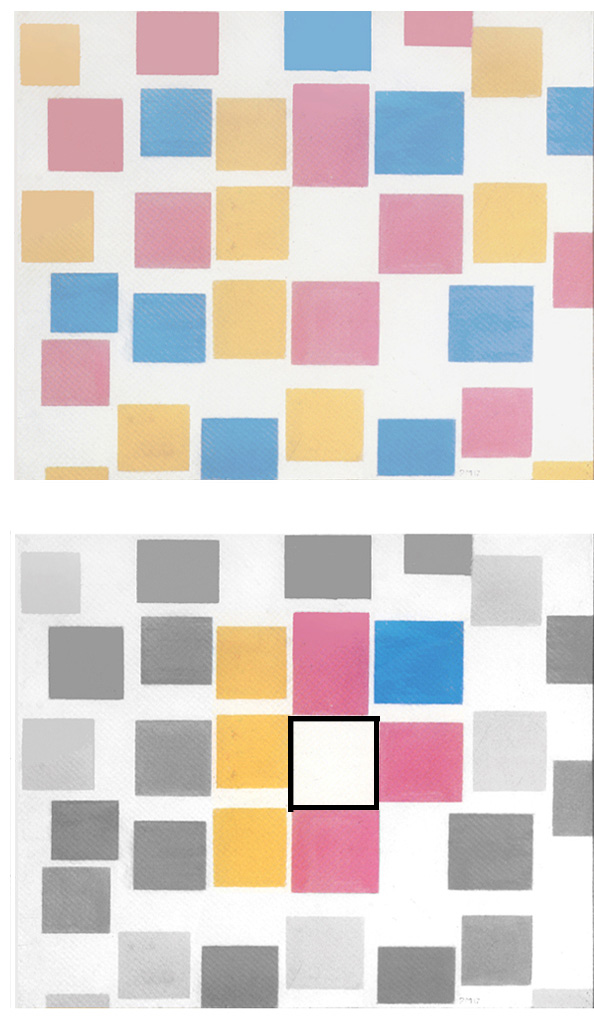

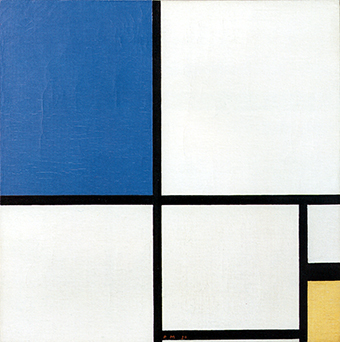

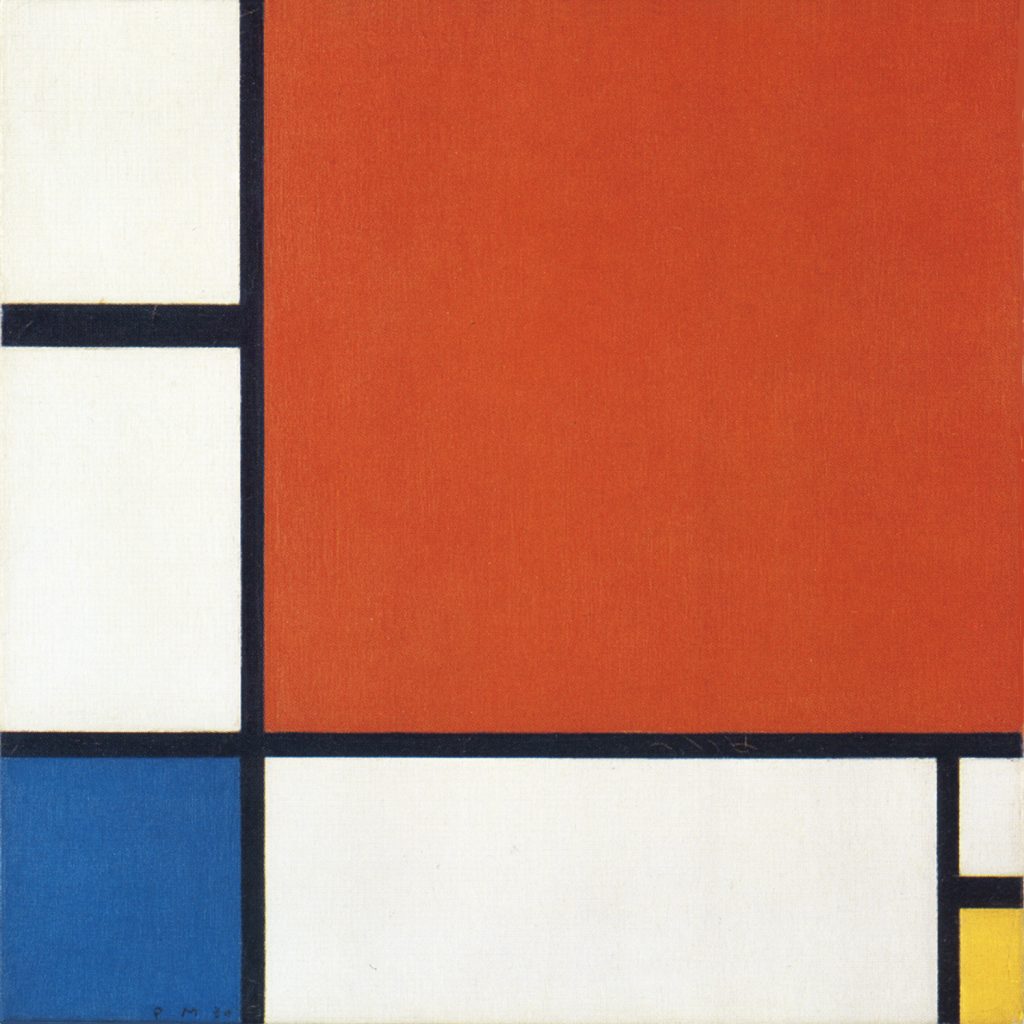

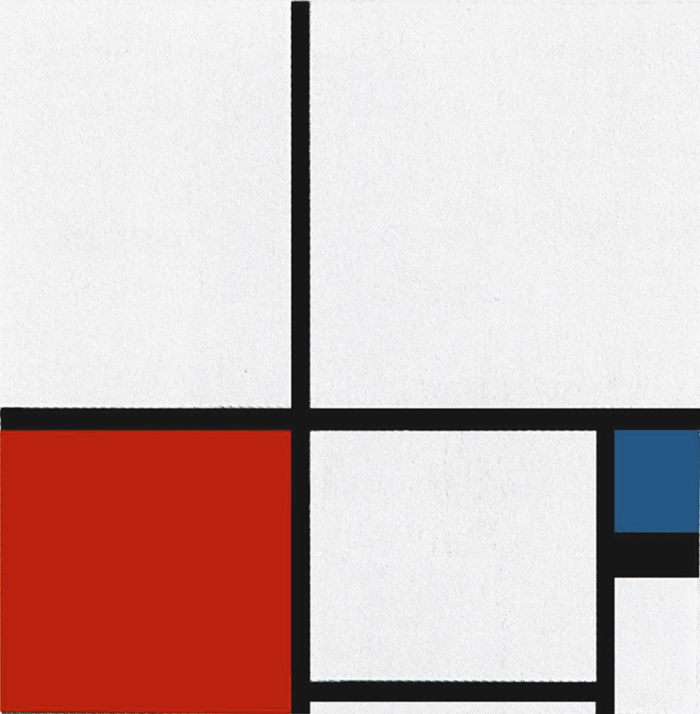

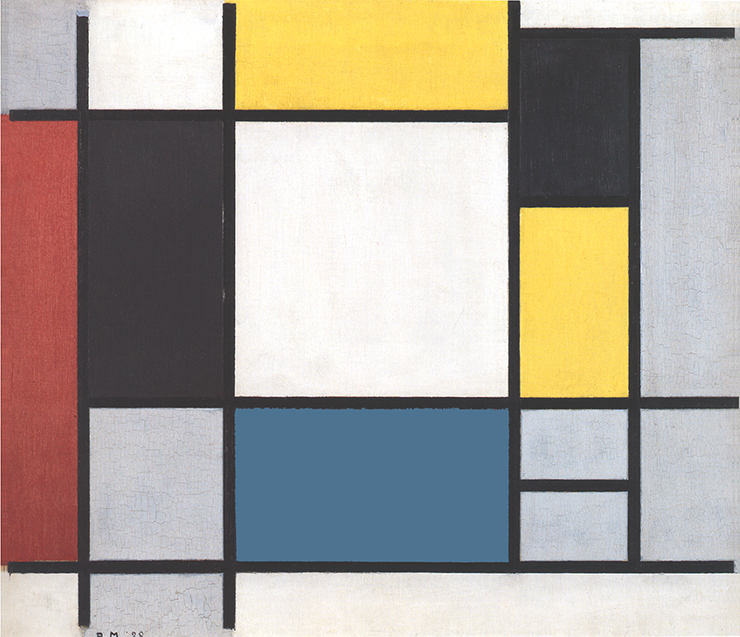

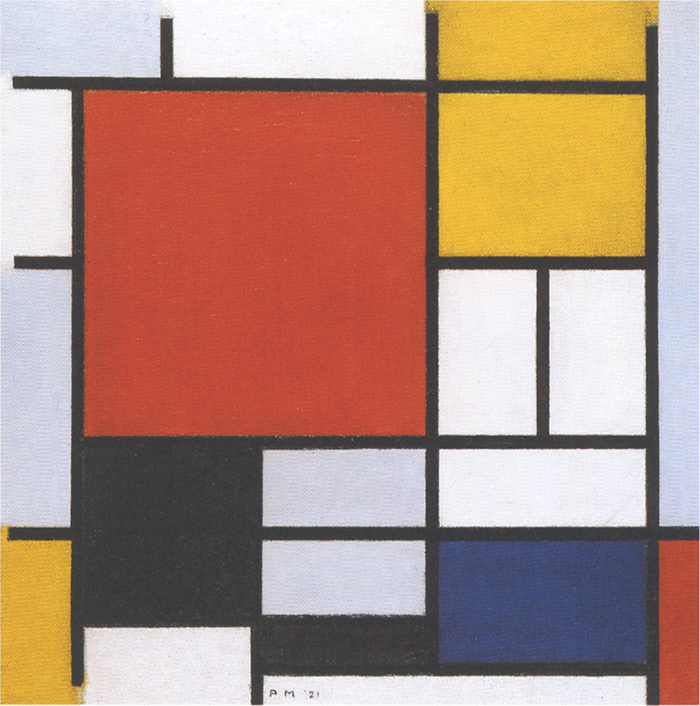

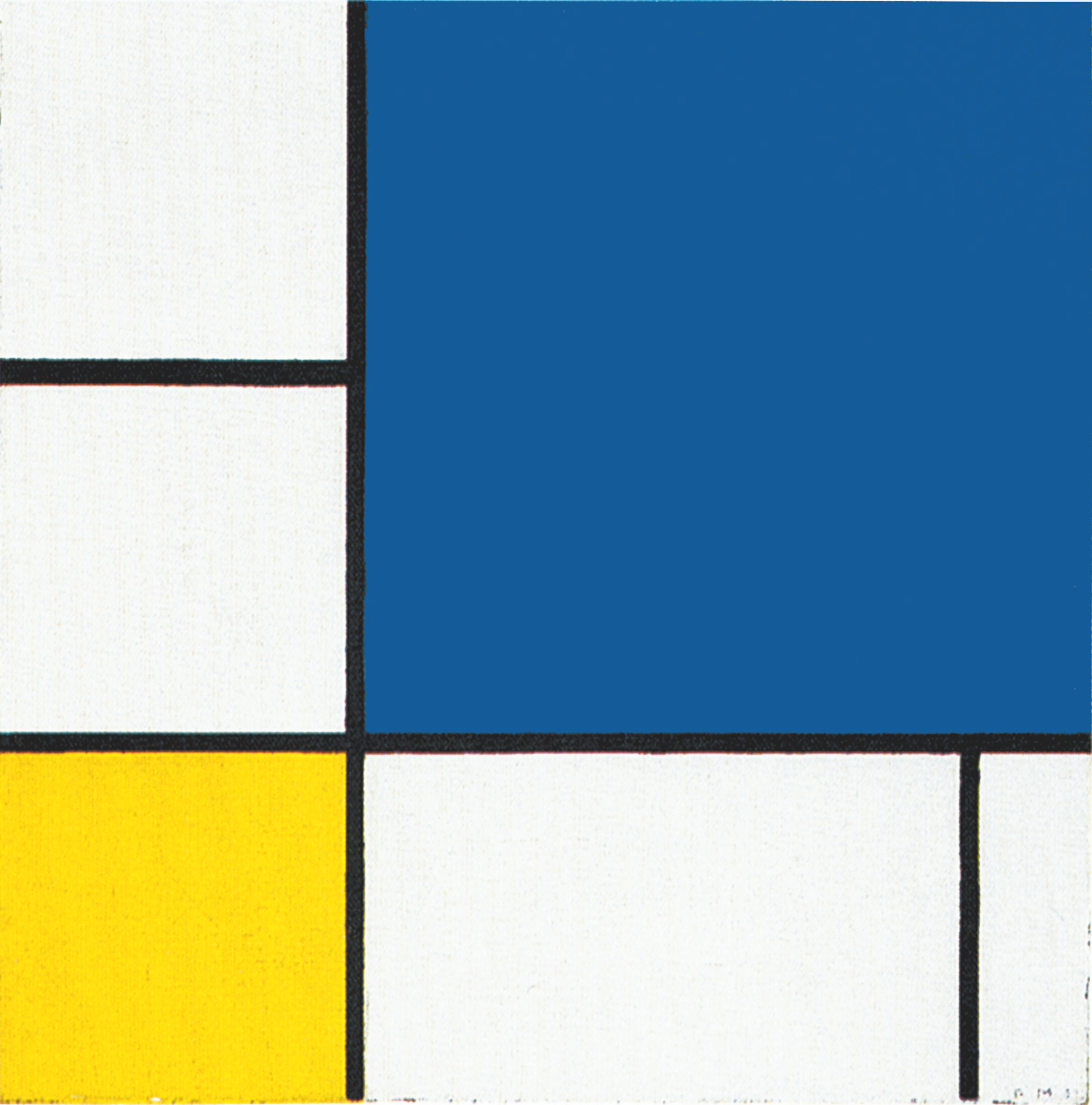

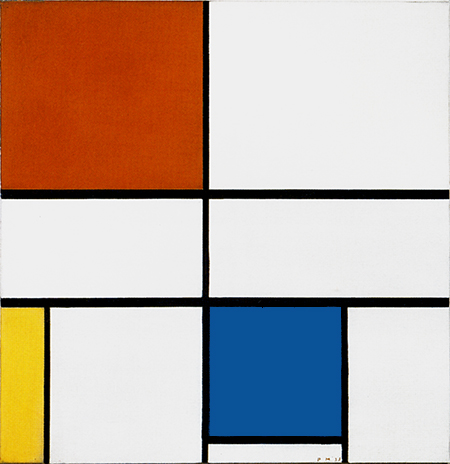

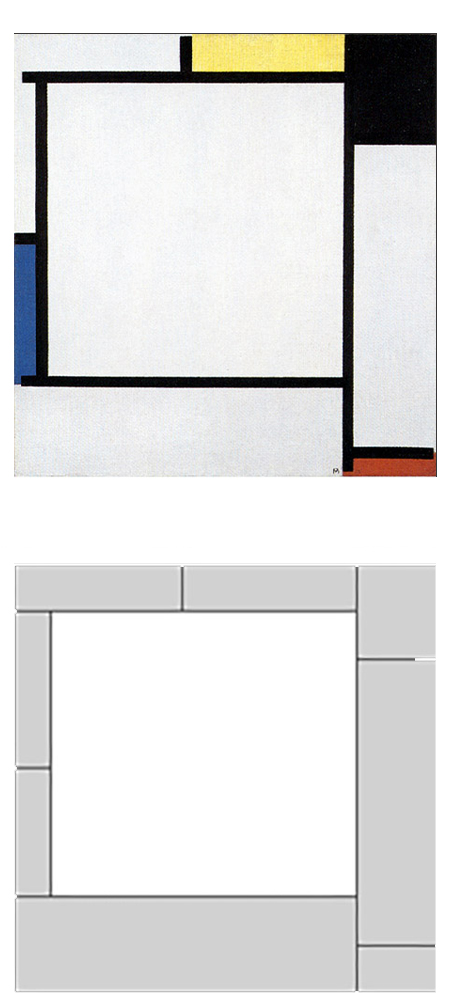

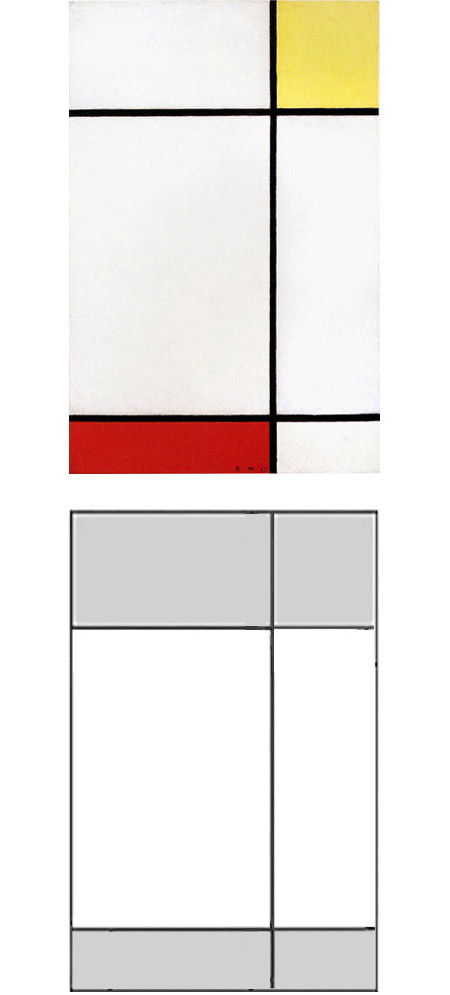

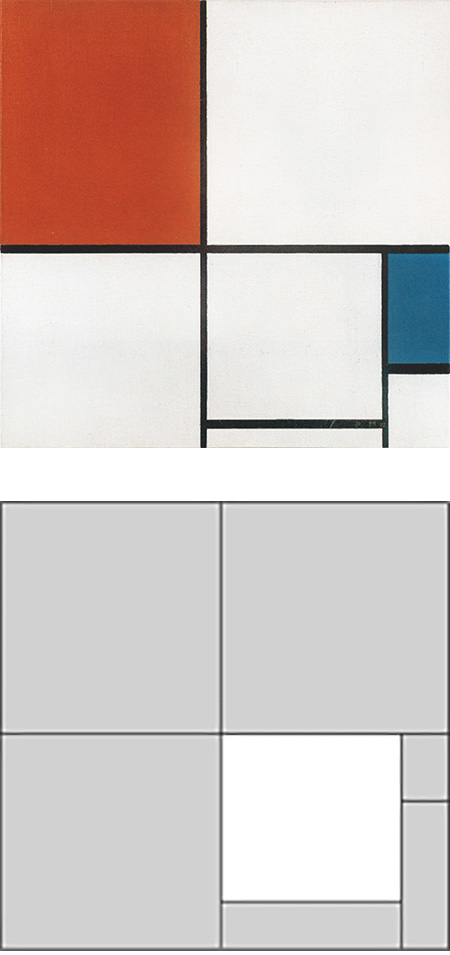

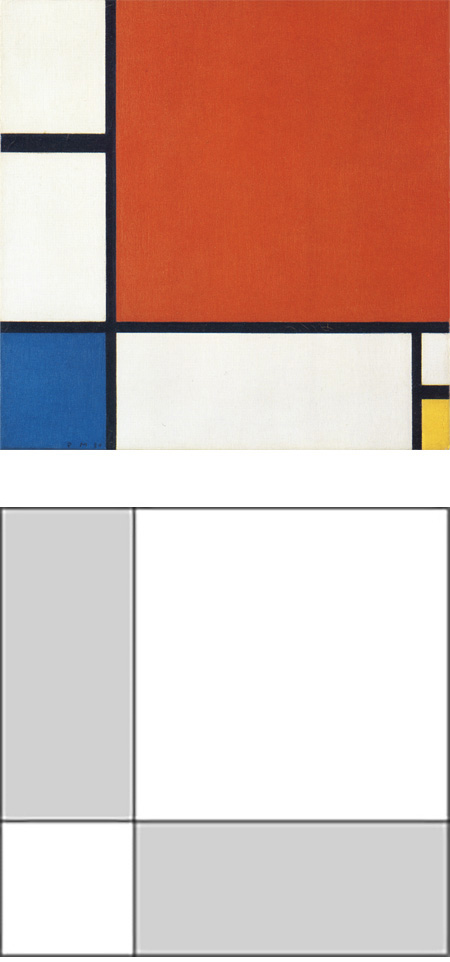

In Pier and Ocean 5 an external unity (the oval) is visually translated for the first time into an internal unity (the central square). Objective unity (the oval) and subjective unity (the square) coexist in Pier and Ocean 5 and, from that moment on, all of Mondrian’s plastic space was to rest on this idea of unity (the square) as the subjective symbol of an assumed and no longer visible objective unity (the oval). On examining the three compositions below, we see how the oval dissolves and a white squared field form emerges from inside the composition:

The square proportion that the painter devised in 1915 would become a constant but constantly transforming element of all subsequent work:

As mentioned, examination of Pier and Ocean 5 reveals that other areas of the composition suggest potential squares, which do not, however, attain the balance of the one in the center. The central square suggests a fully attained equivalence of opposites in a sea of unbalanced situations where other potential squares do not reach the balanced relationship between opposites of the square in the center:

The composition tells us that the balance between opposing drives to which we aspire in order to achieve harmony with ourselves and the outside world is possible (a fully achieved square proportion) but it is always subject to new and unforeseeable imbalances (the unachieved squares and the scattered signs where any possible balanced relationship between opposites is lost) as it is often the case during our lives.

This dialectic between certain and uncertain, multiplicity and a tendency towards unity will guide the artist throughout his life with compositions that present a variety of square proportions intermixed with horizontal and vertical rectangles of different size, proportions and colors where the square proportion suggests a certain tendency toward balance and unity while the mutable rectangles reopen to unforeseeable, imbalanced multiplicity:

Between 1920 and 1936 a dynamic interaction between the one and the multiple will follow four basic compositional layouts.

Layout A: A square proportion is placed in unstable balance by a surrounding asymmetrical set of different measurements, proportions, and colors.

Layout B: An open square area, crossed by a vertical line, emerges from the relationship between two horizontal lines and the vertical sides of the canvas:

In layout C the square is reduced in size, leaving room for three large areas nearing the proportions of squares which, however remain open and therefore appear undefined; same as in Pier and Ocean 5, we are confronted with a fully achieved square and a number of uncertain squares.

In layout D, the square duplicates and remains open appearing once small in blue and once larger in red.

In all these works the square, symbol of unity, opens up to a multiplicity of mutable situations varying in size, proportions and colors.

The relationship between a relatively stable equivalence of opposites and a variety of imbalanced and ever changing situations sketched out in Pier and Ocean 5 will be the guiding thread of Mondrian’s subsequent work.

Reflections on existential meanings of Pier and Ocean 5

Let us return for a moment to Pier and Ocean 5 and consider some aspects of a general character:

Unity of nature and mankind

An infinite physical disproportion exists between the human dimension and that of the natural universe. In certain situations, however, they can assume equivalent value for human awareness and reach an ideal equilibrium taking into account the rationale both of mankind and of nature without, of course, forgetting that human beings are a part of nature.

Mondrian saw the equivalence of opposites as the attainment of equilibrium and harmony between the vertical, symbolizing the Spiritual – which uniquely characterizes the human being – and the horizontal symbolizing the Natural understood both as the outward natural universe as well as the inner nature of human beings. In this perspective, the Spiritual appears to be Natural as well. We shall return on this.

Considering now only the outward nature, what is the the environmental question if not the search for a better balance between the “artificial nature” (concrete, metal, plastic etc.) humans generate and Nature as such? Since human beings are part of the natural universe, this essentially means trying to reach a balanced relationship with the environment reconnecting a part of Nature (mankind) with the whole of Nature.

Environmental issue

There is talk today of the Earth as one unique organism of complexity and of biological diversity to be protected. It is not only the scientific community but also religions that seek to act as interpreters of the environmental question. As I have already noted, ecology is a concrete example of the attempt to redress the balance between mankind and nature, subject and object, what manifests itself in the two-dimensional space of a canvas through the relationship between vertical and horizontal.

Body and mind

This holds both for the subject’s relationship with the object (the external world) and for the subject’s relationship with itself: finding equilibrium between the contradictory drives within oneself, e.g. between the uncontrollable urges of the instinctual life, i.e., human Nature (the horizontal) and the action of controlling and guiding the instincts performed by the mind or spirit (the vertical). In some cases, reason and moral rules oppress and limit the vital impulse; in others, life turns common sense and reason upside down. How are we to get by?

The human search for unity

The human search for unity (be it the idea of a God or the unifying theories of science) is always counterbalanced by the multifarious aspect of Nature. The infinite variety of our world may find a temporary synthesis under the unifying action of the spiritual mind which then must always necessarily open up again to the multiform and ever-changing aspect of physical reality and life evolution. This is what science constantly does. This is what every human being does when, based upon the experience, he changes his ideas of reality.

Emotional drives and ethical rules

As mentioned, when we talk about nature we talk about the outer nature and the inner nature of mankind. For consciousness these are two virtually infinite spaces because our inner world is no less complex and elusive than the immense variety of the outer world.

The sign of equivalence between opposites (the square form) suggests to attribute one and the same value to our nature and to what instead characterizes us as the human species, namely intellect and reason in order to avoid or minimize conflicts between emotional drives and ethical rules; internal imbalances that end up being projected onto the external world to create friction and conflicts between individuals and between individuals and their environment.

Mondrian’s aesthetic space therefore also contains an ethical message calling upon us to balance the opposites and neutralize the imbalances within us before thinking about others and the world as a whole.

How rare and precious are instead those moments in which we see and understand the reasons of both parts of ourselves, when we manage to expand the space of our consciousness to such an extent as to contemplate all the diversity present within us as a dynamic unity.

Duality disappears for an instant. We feel that we are all one and everything outside appears to be in a state of harmony because there is harmony within. Contemplating that synthesis, reveling in the instant of an eternal joy that seems to unite us with the whole (the unity symbolized by the square in Pier and Ocean 5), then opening up again to see things separate and clash with one another in the multifarious disintegrative rhythms of everyday life (the controversial space around the square unit in Pier and Ocean 5).

That idea of unity remains in the heart, a taste of universal life that is no longer revealed in the particular but of which our fleeting emotions and our constant pursuit of equilibrium are a component – albeit infinitesimal – capable of making an essential contribution to the whole.

A masterly use of form transforms an abstract composition made of small perpendicular dashes into a statement of wisdom inviting us to understand that one thing depends on the other in a dynamic equivalence of contrary aspects that, in a static vision of rigid content, work instead to divide consciousness, separating us from ourselves and from the world.

The sky above us and the moral law within

Immanuel Kant spoke of the starry sky above and moral law within. The moral law consists in the rule that accommodates the instincts but keeps them under control. For Mondrian it is a balanced relationship between the natural urges and the control exercised by the spirit, as expressed in the sign of equivalence inside the square. The starry sky is for Kant the whole world, external reality, everything that can influence our inner balance, i.e. all the space around the square in Mondrian’s composition.

The equivalence of opposites means that morality must not be bigoted but also that the freedom is not the unbridled satisfaction of every desire. Kant defined freedom as being able to set oneself rules, i.e. being free to choose rules that are in any case necessary, both in coping with one’s inner contradictions (individual life) and in the relationship between oneself and others (social life).

Form becomes content

In interpreting the formal relations of Mondrian’s compositions, we can develop contents that speak to us about life, not in its fleeting appearances, however, but in its most intimate and authentic ways of being. Mondrian’s talent and intellectual honesty ensure that form acquires depth and reveals his intimate vision of things. With Mondrian form becomes content and aesthetics acquires an ethical value.

Pier and Ocean 5 depicts in a graphic manner ideas which will be expressed twenty-seven years later in the clearest and brightest form with Broadway Boogie Woogie, the last painting Mondrian was able to complete and a marvelous synthesis of his entire oeuvre. The Museum of Modern Art in New York City are very lucky to have both paintings in their permanent collection.

About Cubism

After Paul Cézanne, who died in 1906, George Braque and Pablo Picasso gave strong impetus to the birth of Cubism between 1907 and 1911. In 1915, however, when Mondrian with Pier and Ocean 5 achieved a synthesis of Cubist space, they instead went back looking for unity of composition in the apparent forms of objects.

Mondrian was to say later that they failed to develop the premises inherent in their initial analysis. Braque and Picasso went in fact from Analytical Cubism to what has been erroneously called Synthetic Cubism without pinpointing the precise moment in which the Cubist vision began to live in its own right, becoming space in itself with no longer any need to refer to the limiting form of aa few particular objects. The Dutch painter sought in Cubism the way to express a universal space.

Mondrian replaced an illusionistic use of the pictorial surface (the supposed third dimension) imitating the transitory appearances of the world with a concrete use of the canvas that, without resorting to optical illusions, presents itself as a possible interpretive model of reality, which was for him constituted at the same time by an external space and an internal space in their inseparable dynamic interaction.

The label of Synthetic Cubism attached by critics to the work of Braque and Picasso strikes me as incorrect. In my view, it is not in fact a synthesis but a hasty aggregate of elements as yet unresolved at the level of vision.

So-called Synthetic Cubism was a clumsy attempt to amalgamate the multiplicity generated by the Cubist analysis of reality without subjecting it to a common yardstick capable of uniting the fragments no longer under the apparent form of the individual objects from which they originated but in terms of intrinsic spatial qualities which, in the end, is what really matters in the art of painting. The synthesis was effected without taking into account the data resulting from the analysis.

Synthetic Cubism thus left the fundamental issue of the dichotomy between objects and space unresolved. This contradiction was to become in the hands of Picasso a particular form of Surrealism that consists in seeking a synthesis between different objects without succeeding in breaking away from their apparent form, i.e. without accomplishing a real process of abstraction. As such alchemy obviously cannot work, things become deformed and take on a surrealistic appearance. Picasso’s Surrealism can be described as a sort of rusty Cubism. This is not to detract from works such as Guernica, which remains a masterpiece of painting, but rather to scale down the role of inventing genius attributed to Pablo Picasso in the development of modern plastic space.

next page: toward Neoplasticism

back to overview

Copyright 1989 – 2025 Michael (Michele) Sciam All Rights Reserved More