Please note: If on devices you click on links to images and/or text that do not open if they should, just slightly scroll the screen to re-enable the function. Strange behavior of WordPress.

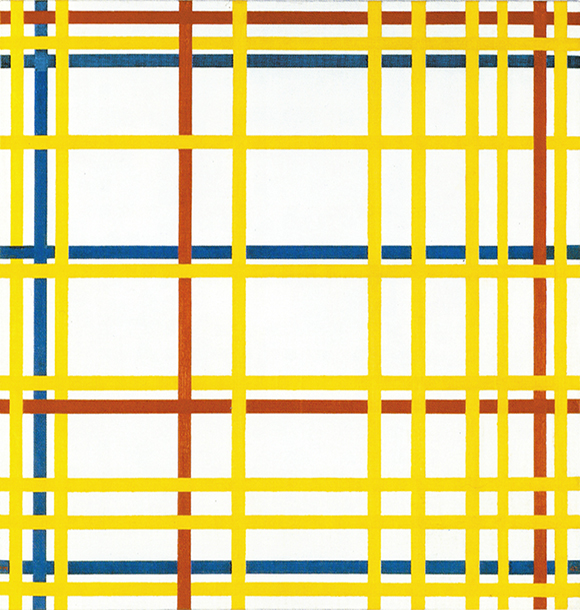

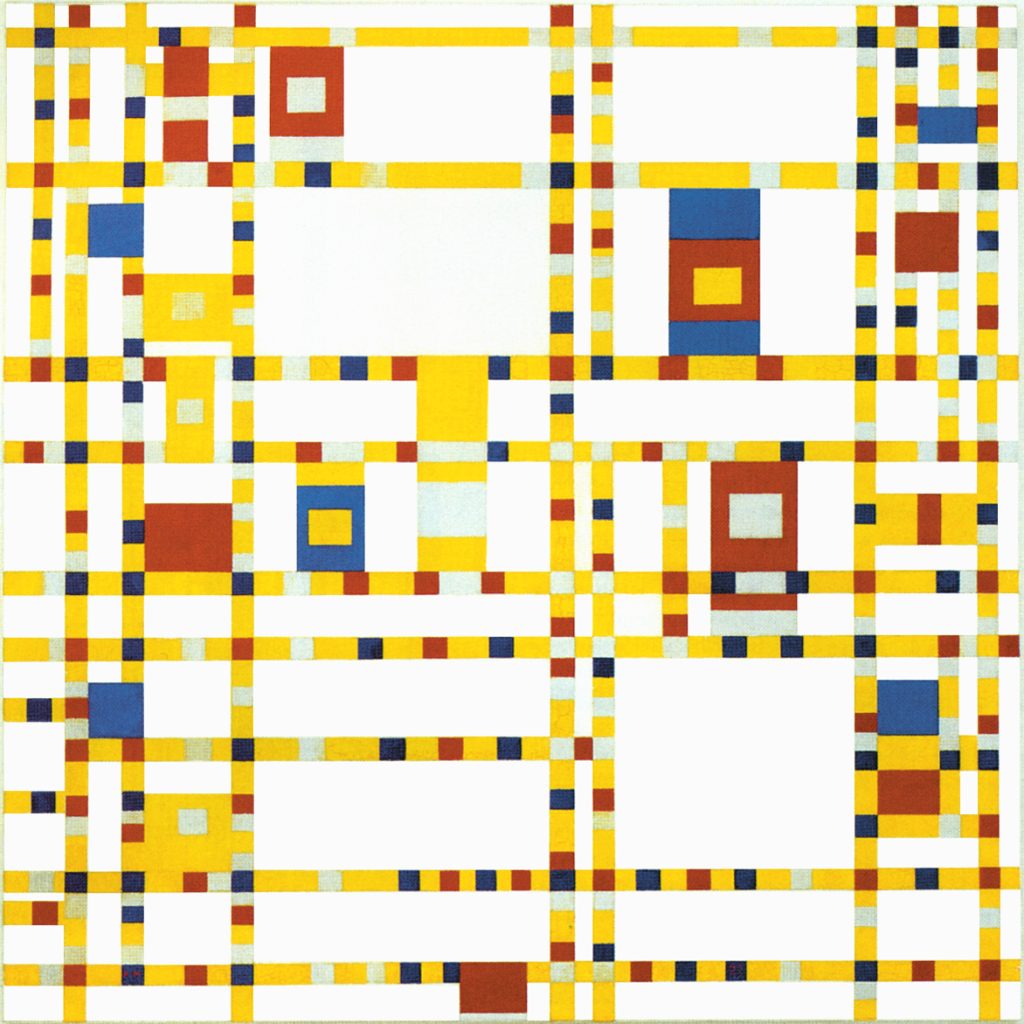

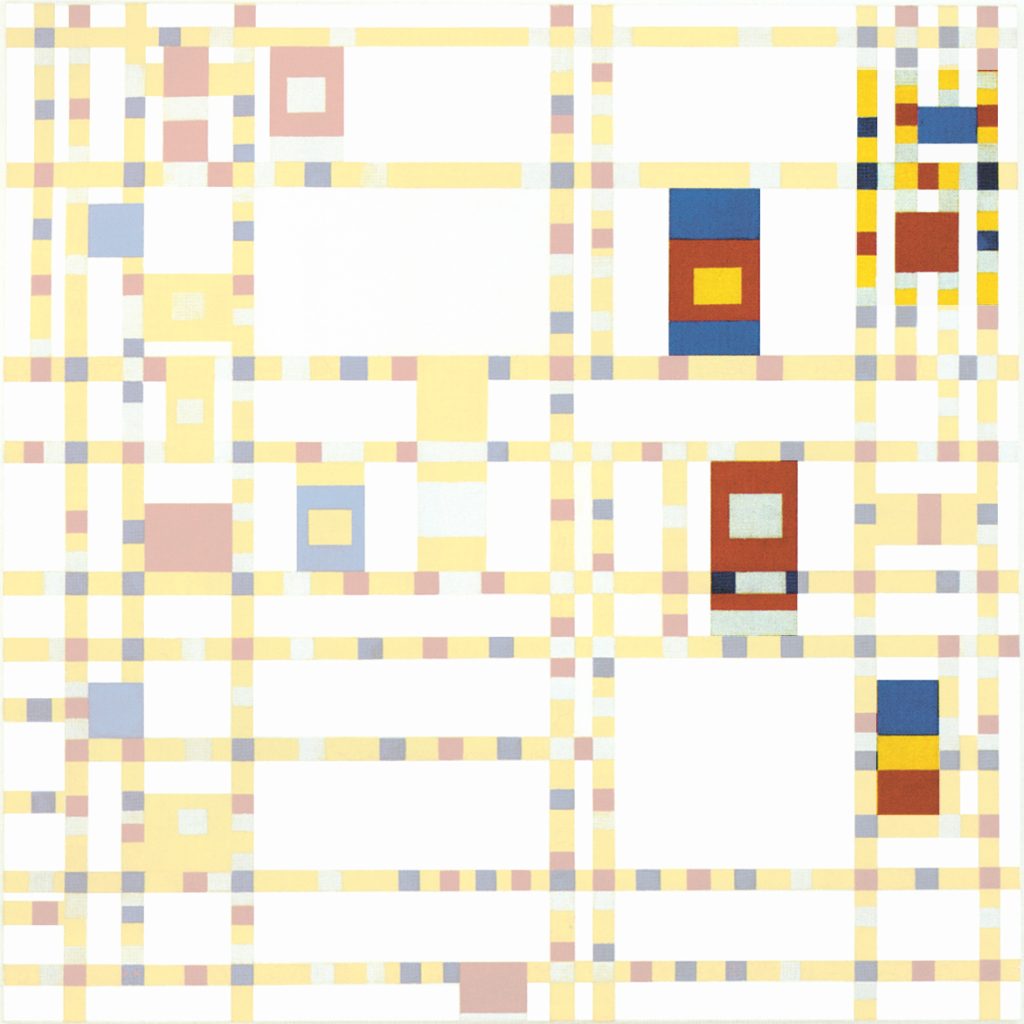

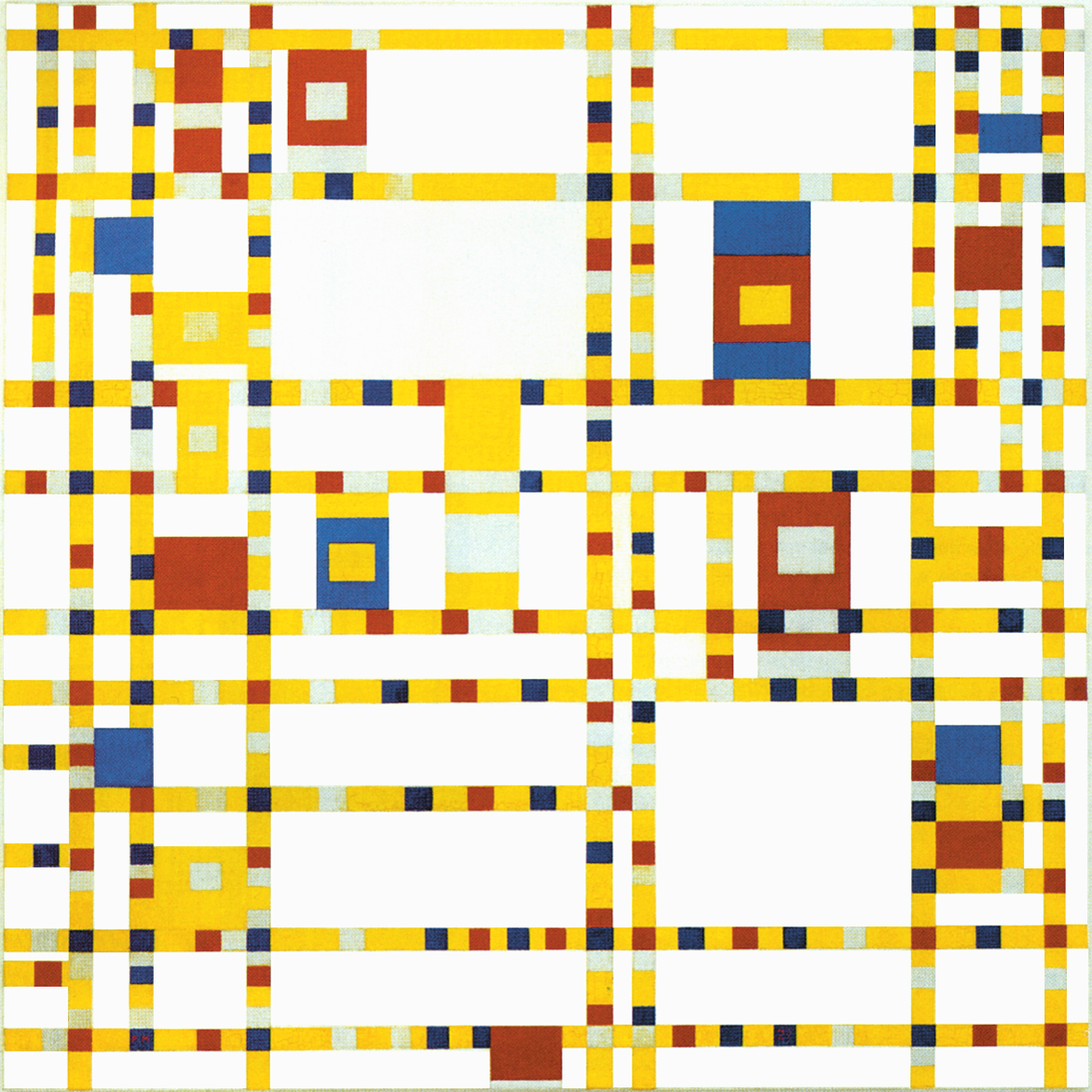

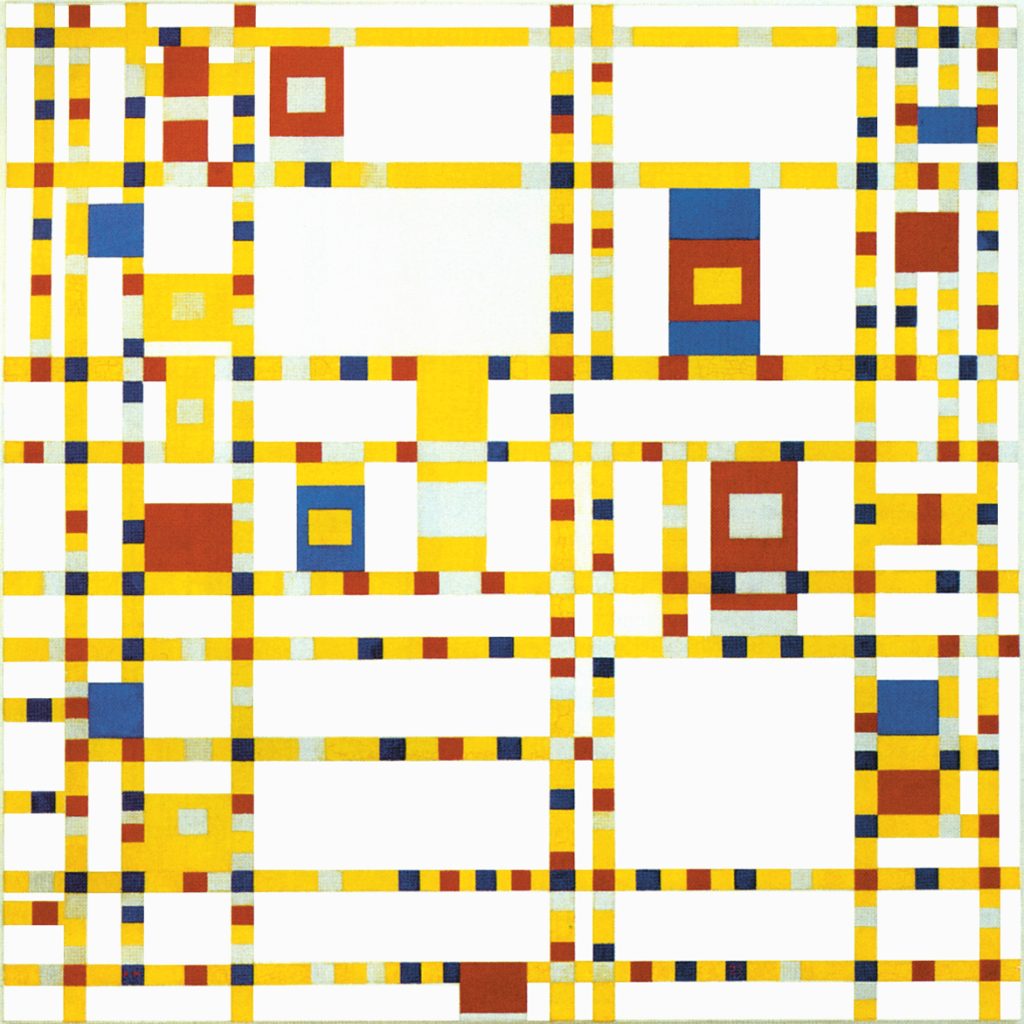

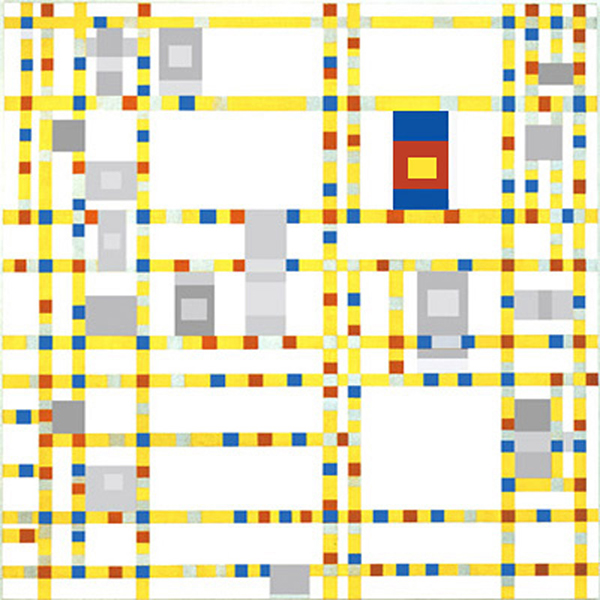

This page offers an in-depth examination of Mondrian’s last accomplished work Broadway Boogie Woogie. This painting represents a compendium of the entire oeuvre the painter produced between 1899 and 1943 and offers a magnificent synthesis of the artist’s new vision of reality.

Oil on Canvas, cm. 127 x 127

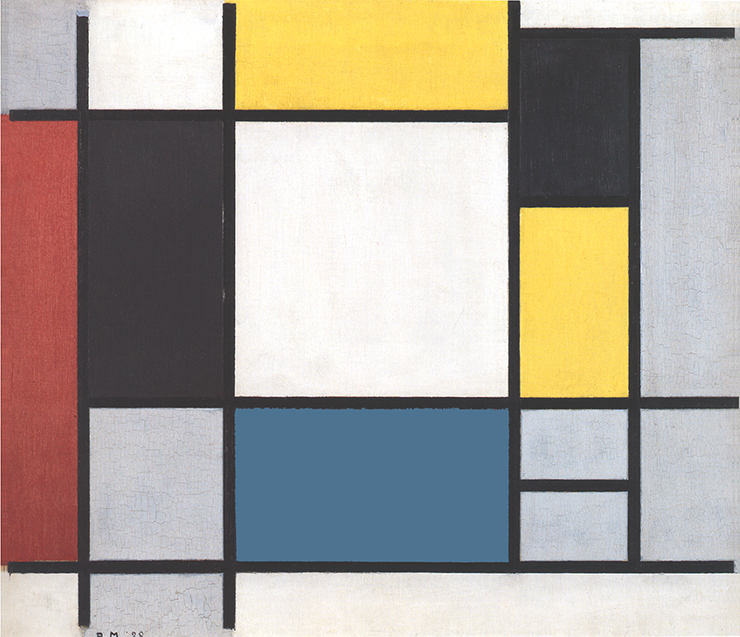

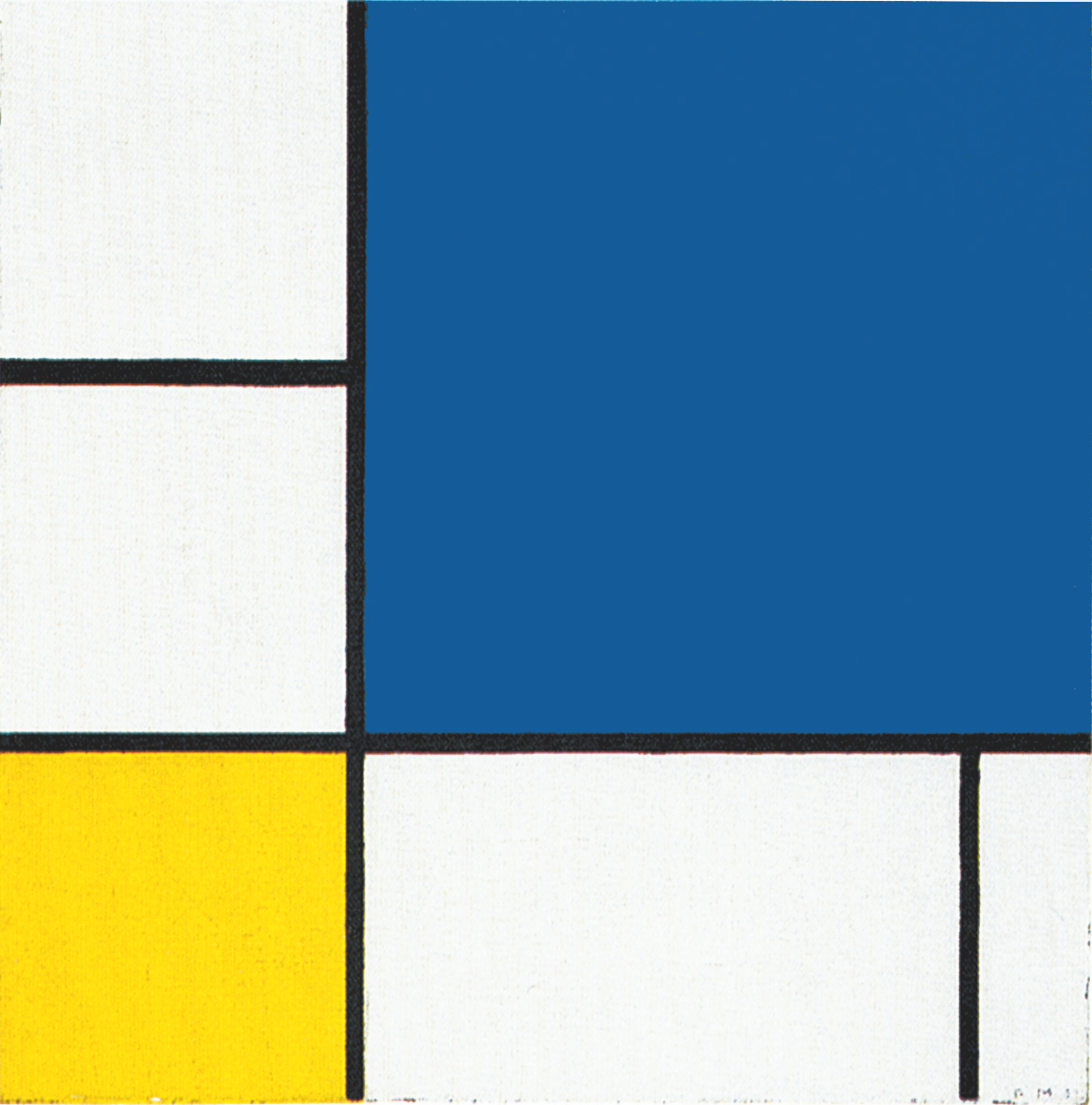

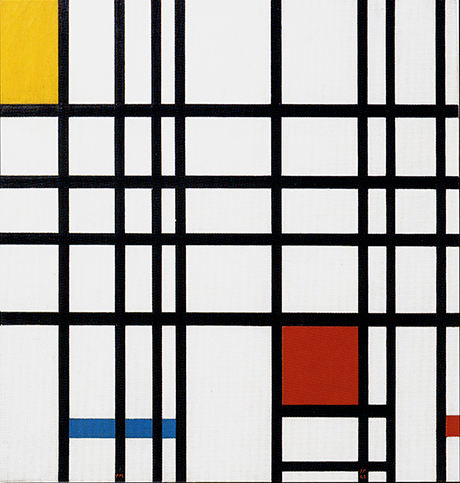

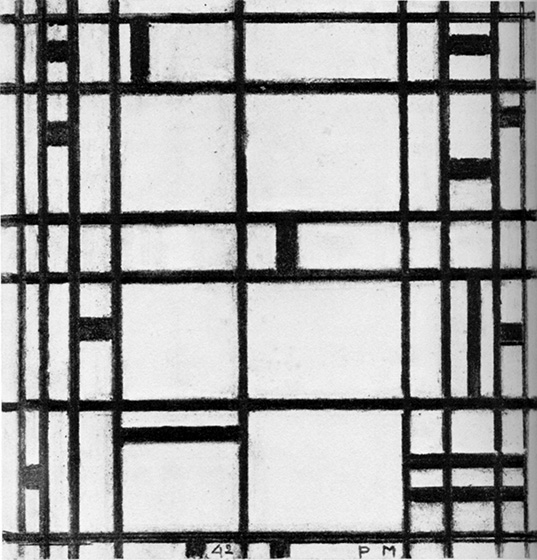

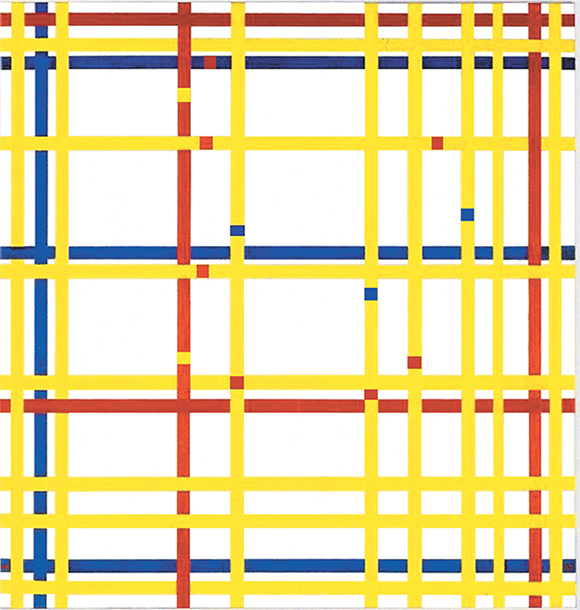

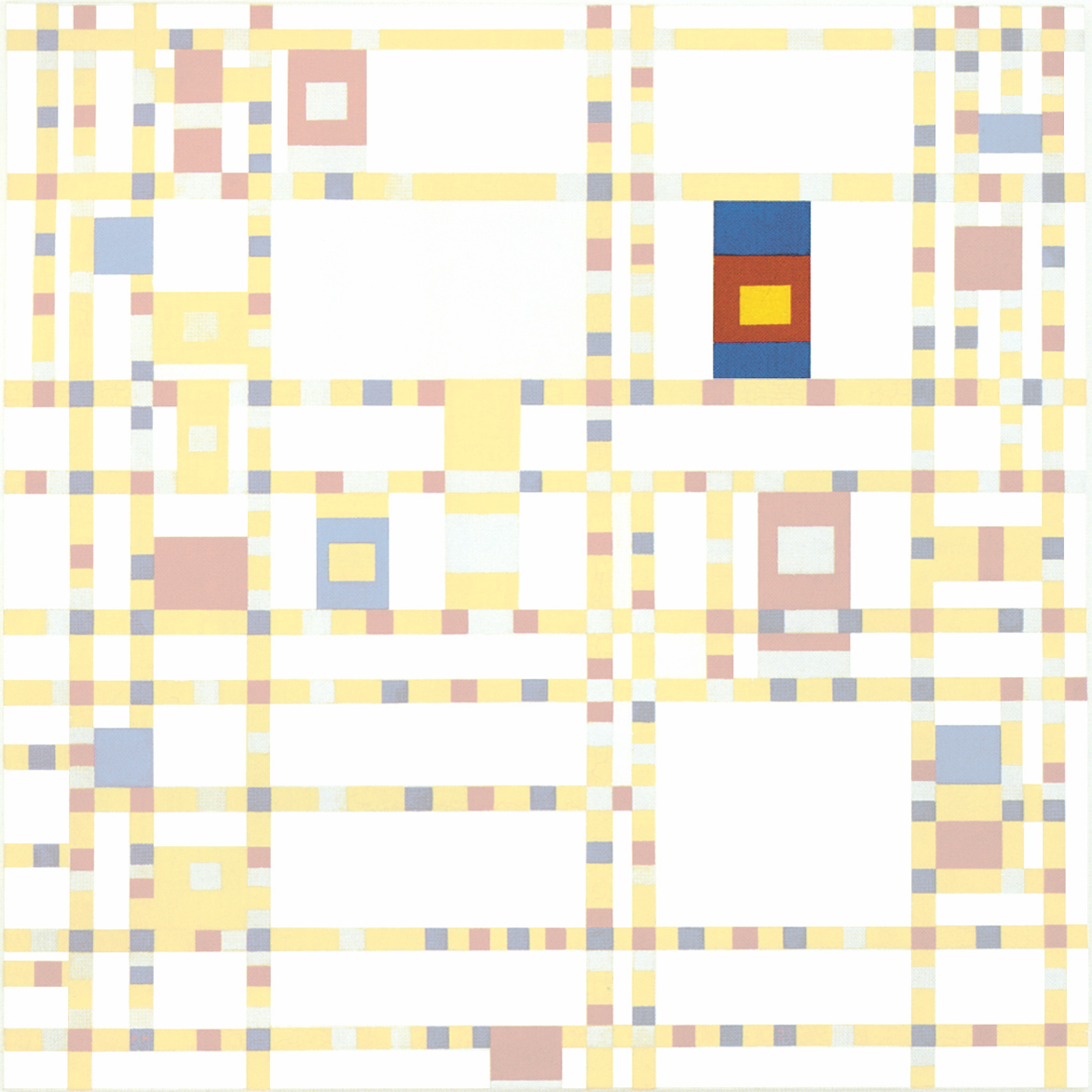

In order to understand the genesis of the composition, it is necessary to start from the preceding canvas New York City.

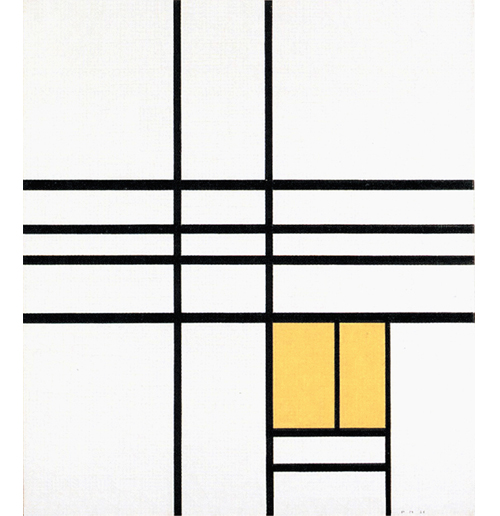

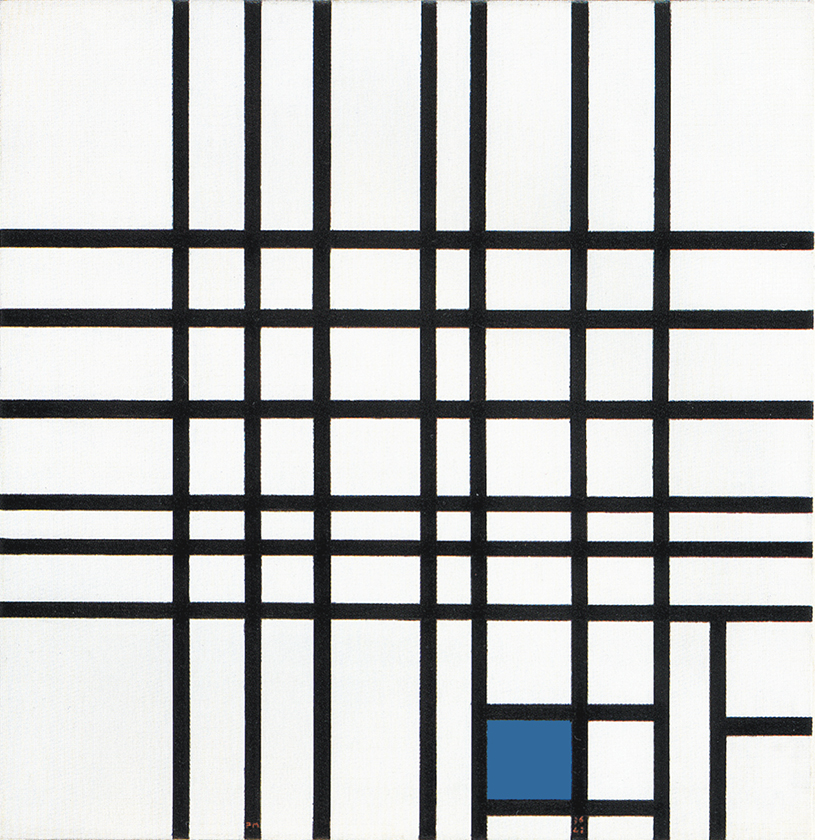

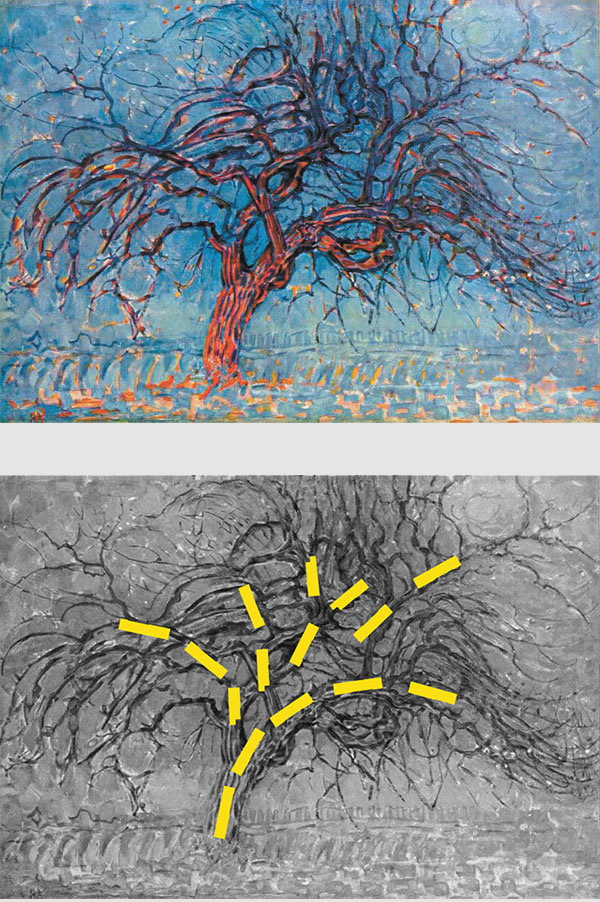

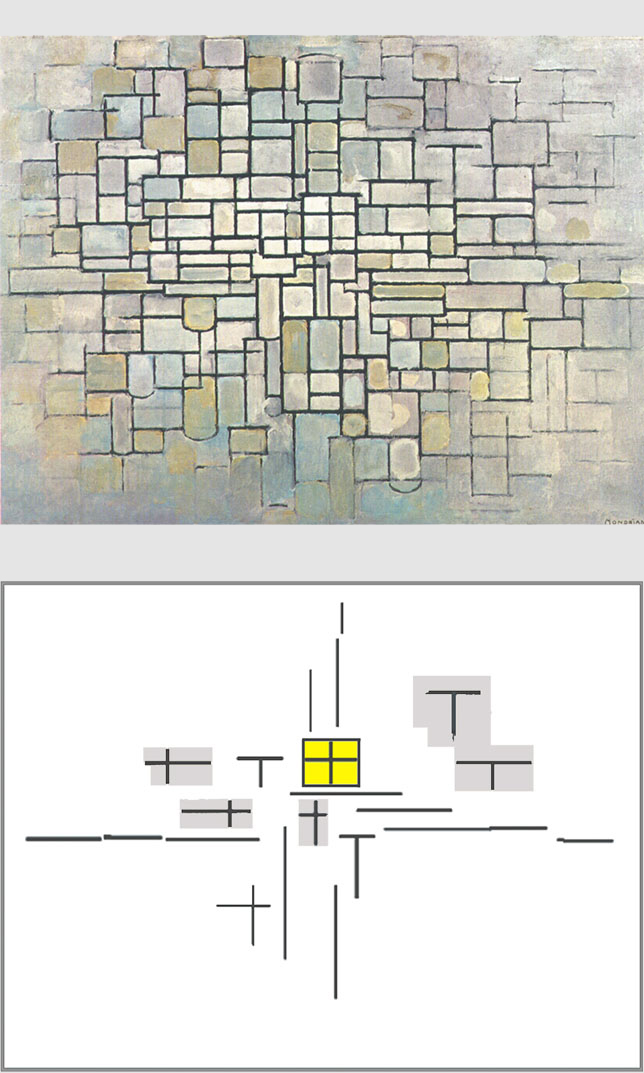

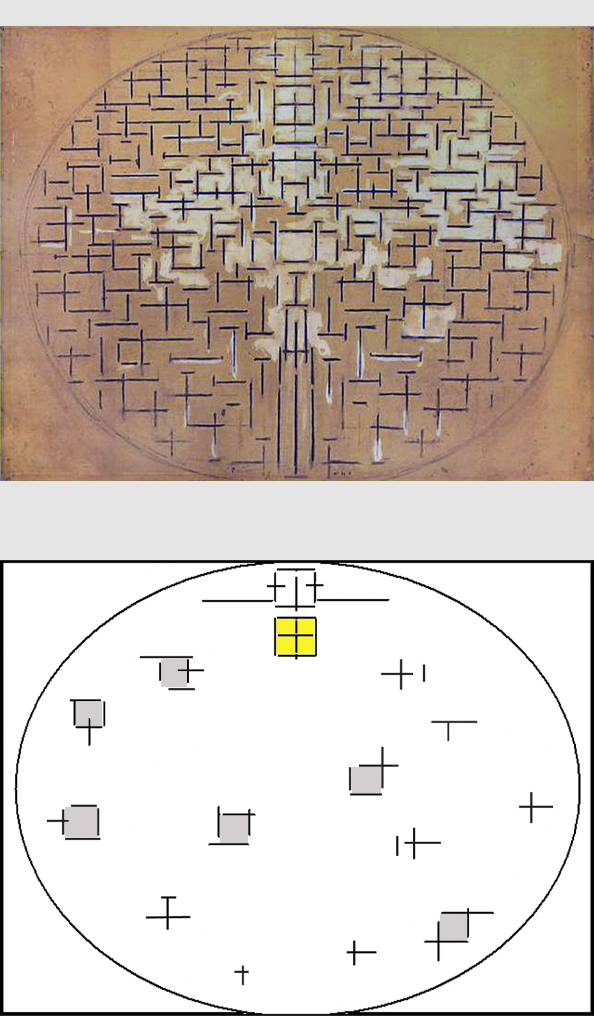

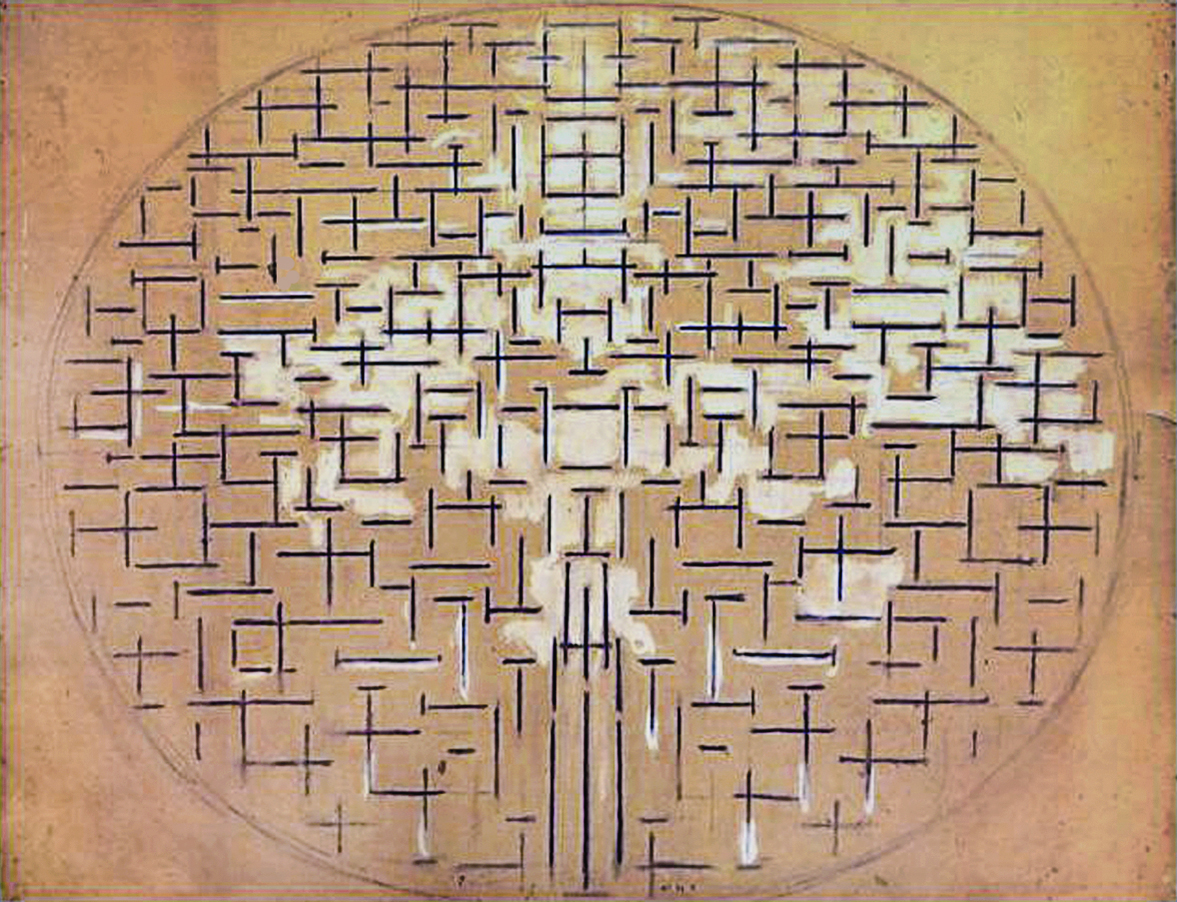

As seen in the previous page, the guiding thread of the evolution process which took place between 1915 and 1942 was a continuous interaction between a multiplicity consisting of mutable relationships between opposites (horizontal and vertical, lightest and darkest colors) and a square proportion which represents the moment when horizontal and vertical reach the equivalence and a changing overbalancing duality is transformed into a balanced unity.

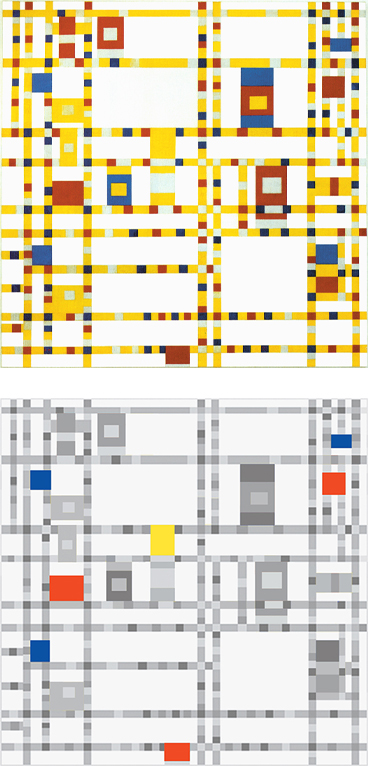

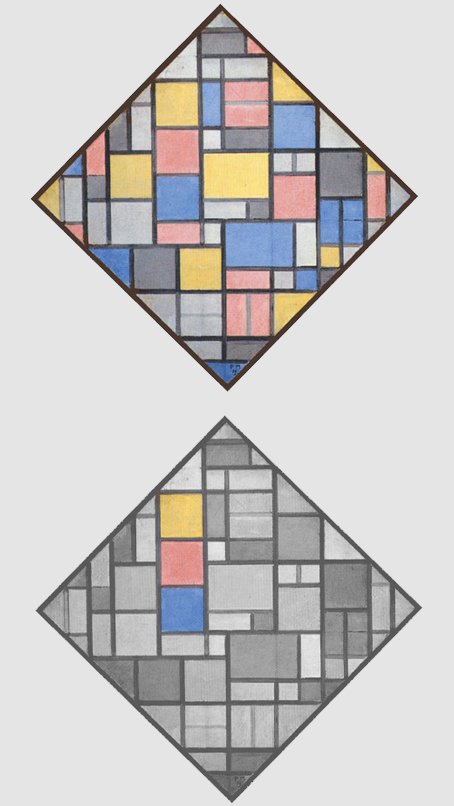

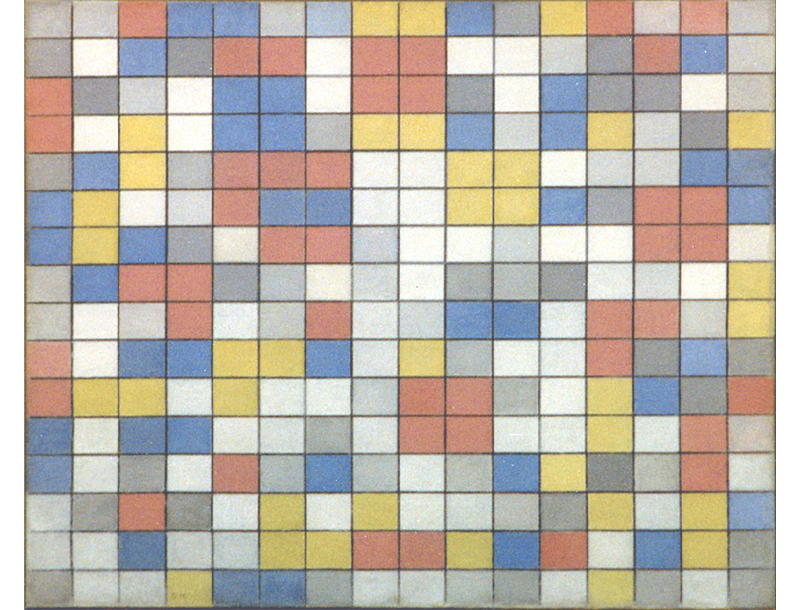

Between 1915 and 1942 we have seen a continuous interpenetration between unity (the square proportion) and multiplicity (planes and lines of different size, proportion and color):

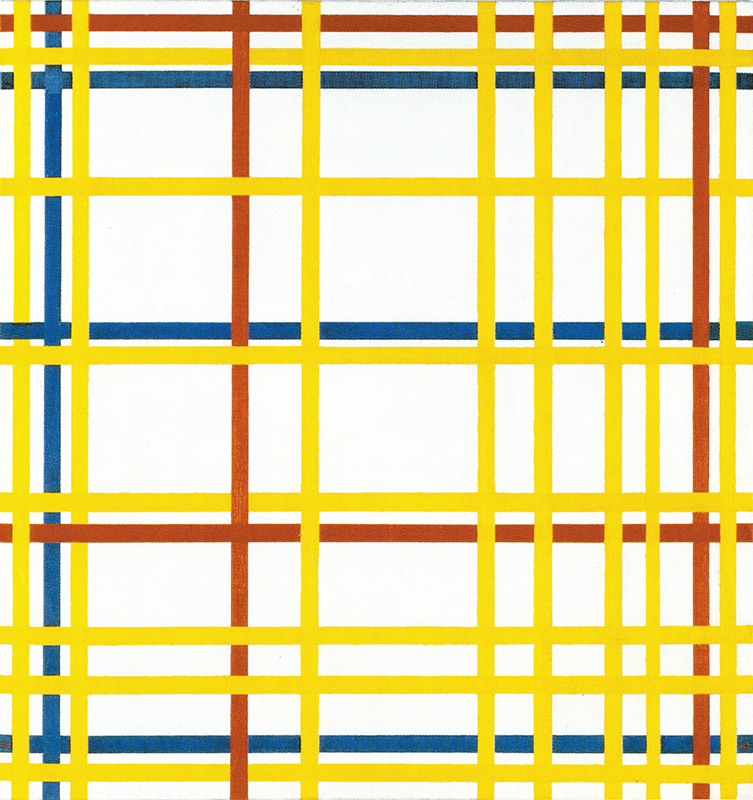

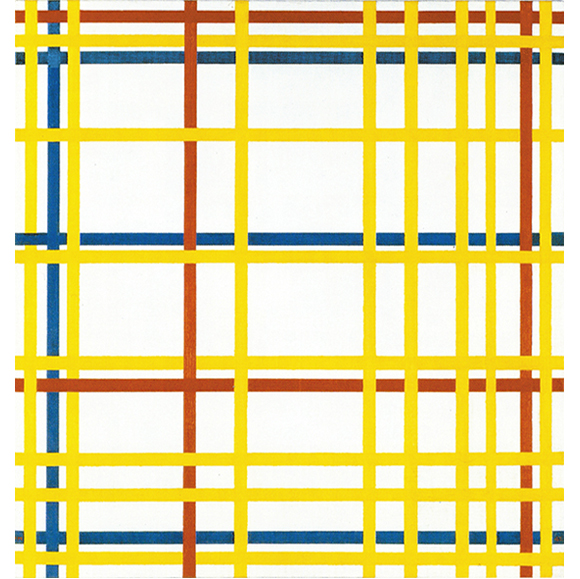

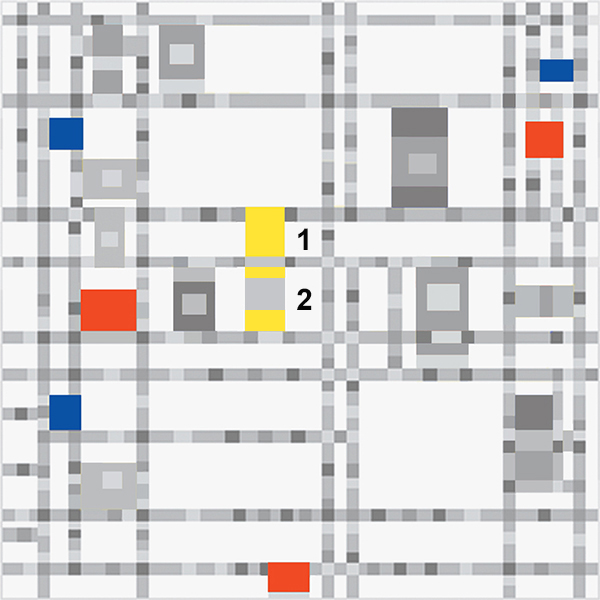

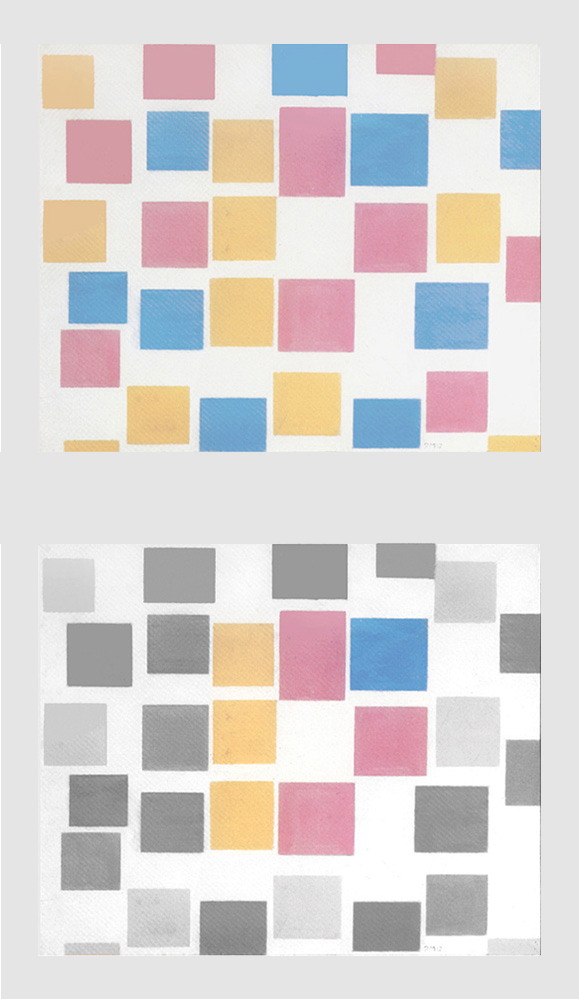

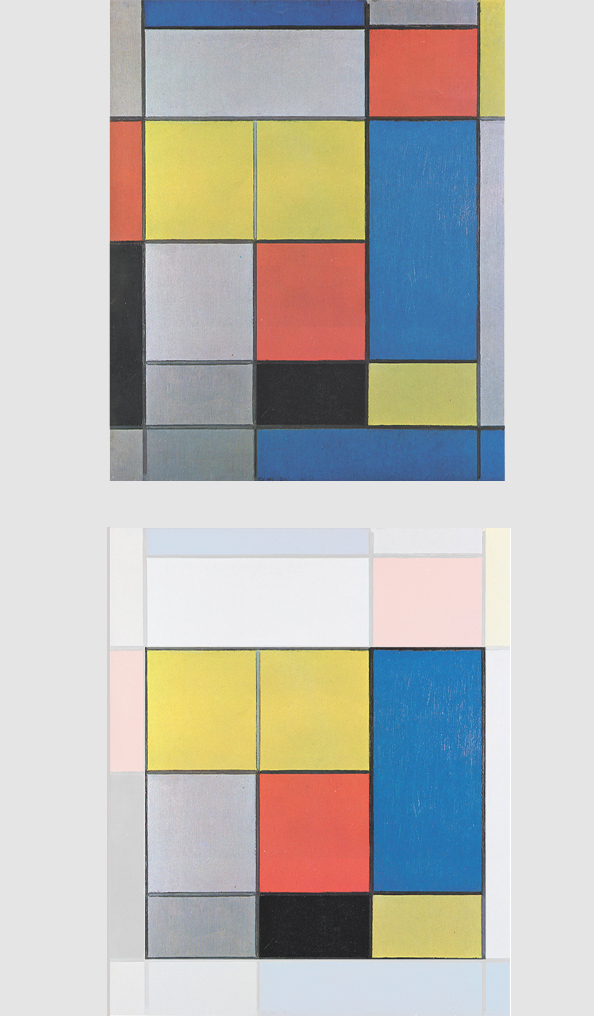

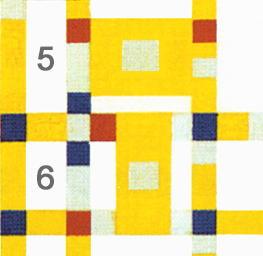

On observing the four paintings above, we can see how over a span of twenty years a white square field (1920) absorbed color and multiplied all over the surface of the canvas (1942) changing in terms of position, proportions and colors. The single black and white unity of 1920 has undergone interpenetration with manifold space and is in 1942 wholly imbued with color and dynamism. Seven square forms generate and dissolve in a variety of combinations between yellow, red and blue lines:

The permanent black and white square unit of the 1920’s has now become dynamic and multiple. Even perhaps too much.

In Fig. 4 the eye scarcely has time to identify a more stable relationship between opposites (a square) before finding itself immersed in the dynamic and continuous flux of the lines. This happens because when color was applied to the lines, the former colored planes disappeared and the painter found himself grappling with compositions in never-ending development:

In all previous Neoplastic works planes expressed finite space and straight lines virtually infinite space. Between the planes and the straight lines we had linear segments that are finite sections of the straight lines.

In Fig. 4 the dynamic space conveyed by the straight lines seems to overwhelm the more measured and constant aspect previously expressed with segments and planes; infinite space prevails over finite space and multiplicity over unity. Fig. 4 lacks a stable and more durable component to counterbalance the dynamic, never-ending continuity of the lines and thus suggest a certain degree of spatial permanence.

While the need felt as from 1936 had been to open up unity (the square) to multiplicity:

it was now necessary to re-establish a greater degree of synthesis and constancy in a space that had undergone considerable multiplication in the meantime and continued uninterruptedly with the lines alone (1942).

Avoiding illusionistic space

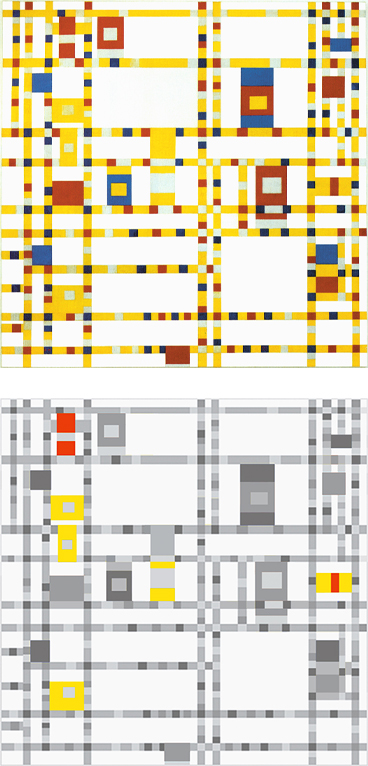

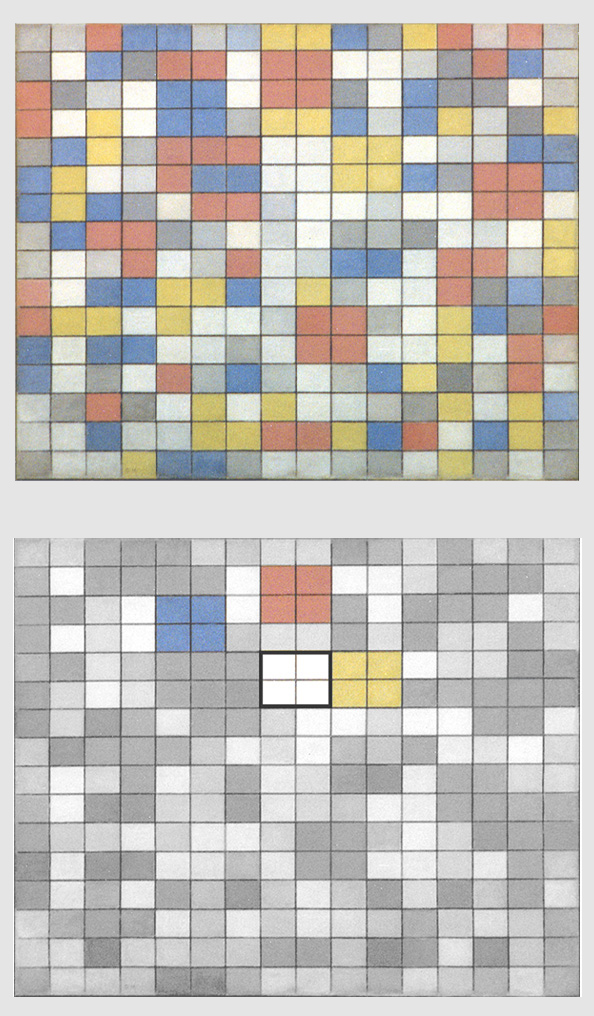

Another aspect that appears unsatisfactory in Fig. 4 is the fact that the points where lines of different color intersect are no longer marked by a single homogeneous plane, as happened with the black lines, but instead by the predominance of one color over the other. The colors seem to be on three different planes, with yellow, red, and blue appearing respectively on the first, second, and third plane:

This superimposition creates a sort of three-dimensional effect with which Mondrian could hardly be satisfied, since one of his aims had been precisely the elimination of any perspective-based illusion of supposed and nonexistent third dimensions in order to express reality in the two real and concrete dimensions of painting. The problem arising as from this moment was to bring the three different planes of the yellow, red, and blue back onto a single plane.

Re-establishing an homogeneous plane

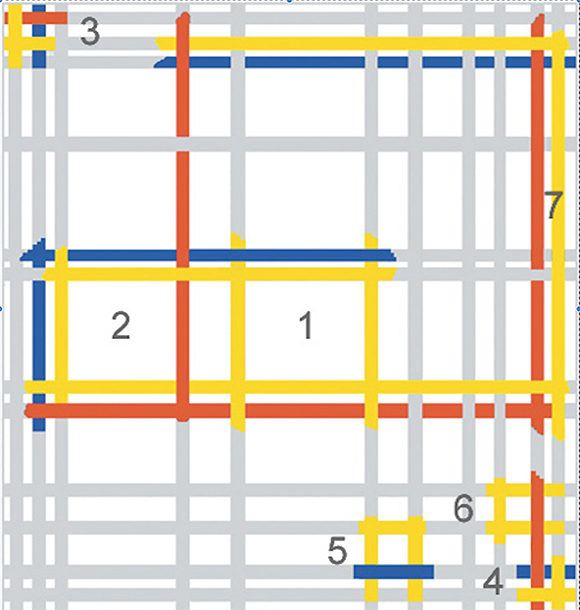

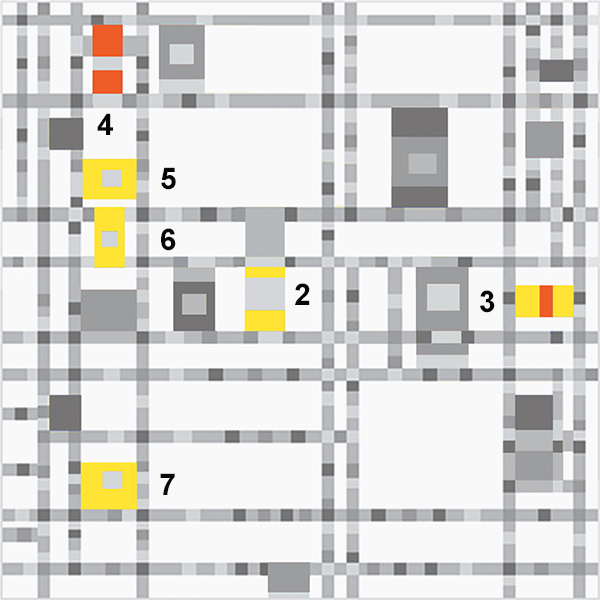

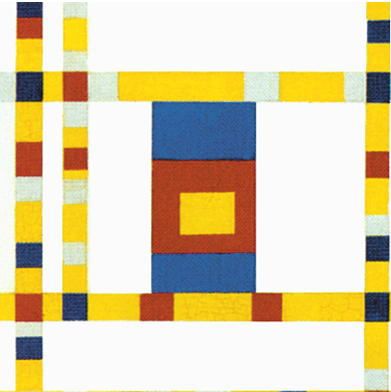

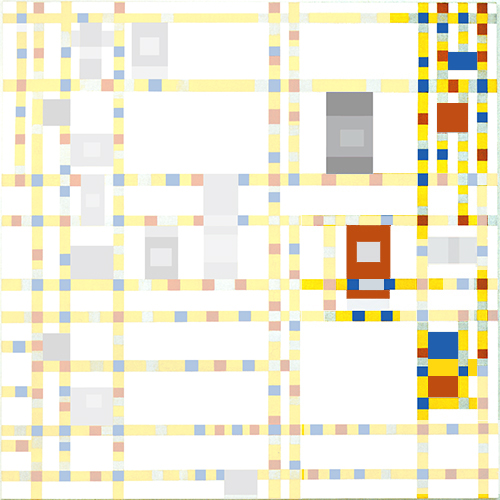

Fig. 4 – Diagram C shows how the predominance of one color over the other cen be resolved by ensuring that each line allows the section covered over to reappear shortly after:

Diagram C

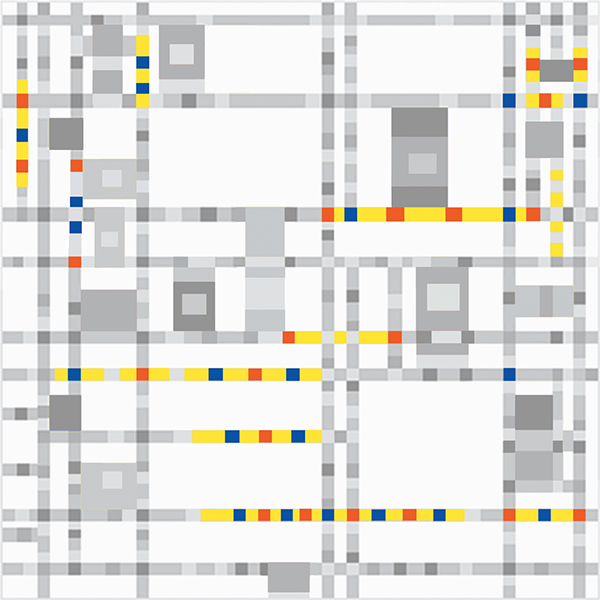

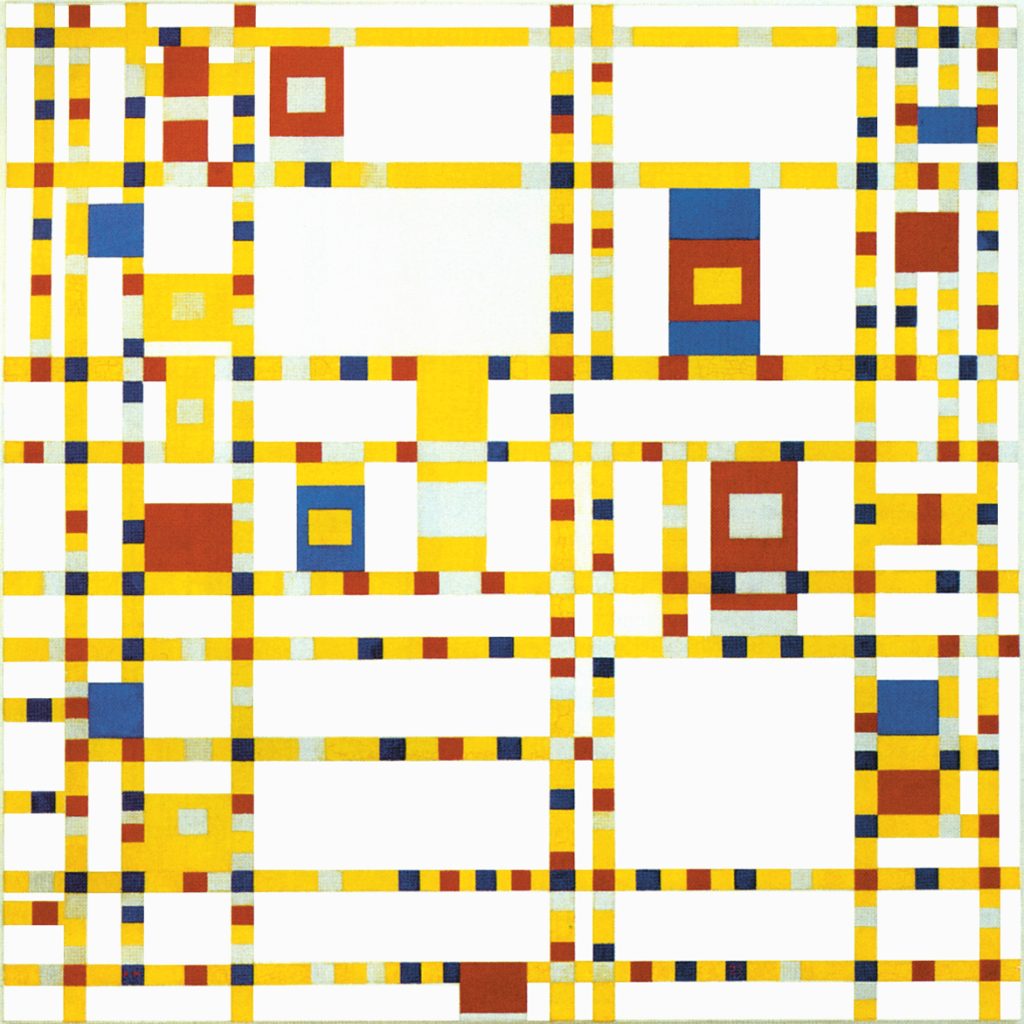

A single plane is re-established and the three colors are brought together while preserving their specific qualities: sections of yellow, red, and blue begin to interpenetrate within every line in the shape of small squares and this gives birth to Broadway Boogie Woogie:

Broadway Boogie Woogie, 1942-43,

Oil on Canvas, cm. 127 x 127

Studies for Broadway Boogie Woogie

From now now I will refer to New York City as NYC and to Broadway Boogie Woogie as BBW.

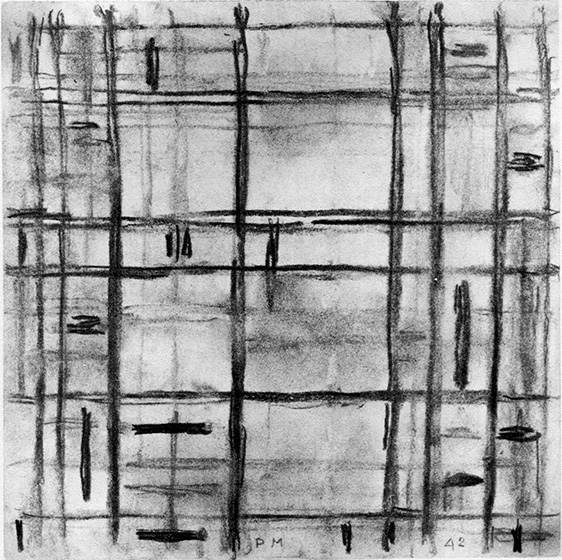

The existing bibliography indicates two certain studies for BBW: Study I and Study II. The first sketch seems to have been made in one go and the second, which is more sharply defined, to clarify the ideas of the first:

In the two studies Mondrian drew a series of perpendicular lines that run uninterruptedly all the way through the visual field, as in Fig. 4. He then inserted between the lines some short segments that, by virtue of their proportions, look like small planes in the second study.

In the two studies Mondrian focuses precisely on this transition from lines to planes, from virtually infinite space to finite space, and expresses it by means of small segments that are, however, no longer black delimiting fields of color as throughout the European Neoplastic phase. As from 1941 the lines are colored and thus the small segments in Fig. 7 become small planes of color when they increase in thickness.

It should be recalled in this connection that lines of increased thickness seemed on some occasions to suggest planes back in 1925, 1930, and 1933.

The second study clearly shows the artist’s intention to channel the dynamic and continuous space of the lines toward finite and more constant relations. Some segments are clearly vertical, some markedly horizontal, and some display an equivalence in which horizontal and vertical are reciprocally neutralized. Originating in the line and tending toward the plane, the segments provided Mondrian with the way to express a finite and more constant dimension inside a space based exclusively on lines as it is the case with NYC:

This was to mark the point of transition from NYC to BBW, where areas of color are generated in the form of slices of finite space suggesting concentration and greater constancy that counterbalance the unbridled movement of the lines. Hereinafter we can see in summary how this transition took place.

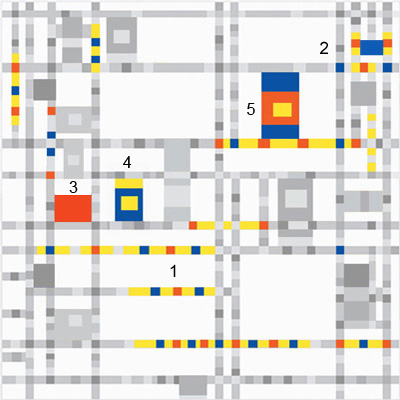

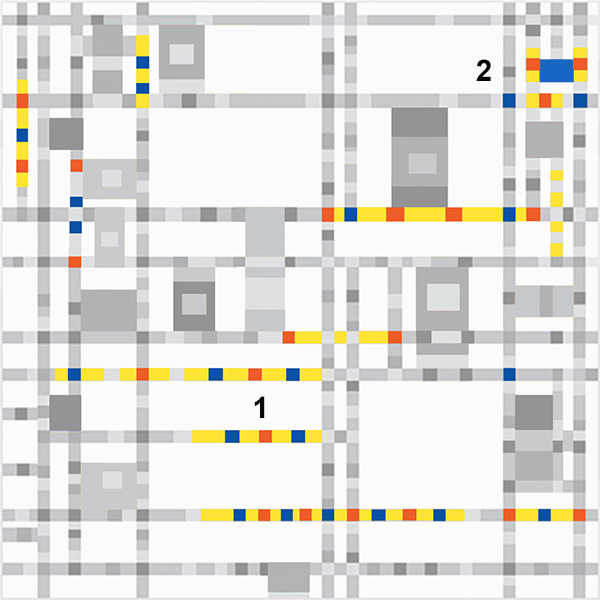

An imagined interpenetration of the NYC lines (Diagram C) generates a multiplicity of small fragments in BBW:

Some fragments join up with others to generate symmetrical configurations along the lines (Diagram X – Section 1 and elsewhere).

An horizontal correspondence between two vertical symmetries with a red center can be seen in section 2. Through the act of contemplating a horizontal relationship between two vertical symmetries, we actually generate a field of greater extension, i.e. a plane. In that very point, we see the birth of a small blue plane and then of other planes of one or two different colors distributed over the entire surface of the painting (Sections 3, 4 and elsewhere).

Section 5 highlights one plane where all three primary colors reach a stable synthesis. The multiplicity of small fragments colored yellow, red, and blue, which disrupted our visual field at the beginning of the process by keeping the eye in constant motion, reach a unified configuration with the plane highlighted in section 5.

BBW shows a process through which a space of virtually infinite expansion (NYC) concentrates into a finite dimension:

This is the finite and more durable component that was missing in NYC to counterbalance the dynamic, endless flow of individual lines.

We shall now re-examine in detail the process we have just observed in synthesis. In order to do this, I have drawn up diagrams in which I have broken down and analyzed the composition. The diagrams should not be intended as an indication of how Mondrian did progressively paint the canvas, rather as a visual aid to understand its meanings.

Broadway Boogie Woogie in detail

In one of his essays Mondrian has written: “The straight lines intersect and touch one another tangentially but continue uninterruptedly.”

In the eyes of the artist the lines are never ending entities. The Neoplastic lines serve to connect the limited space of the canvas with the virtually infinite space of reality of which the work of art constitutes a part; a part which aims at ideally representing the whole in its essence. “Art must express the universal” said Mondrian.

The opposite straight lines are a plastic symbol of the endless physical extension of the outer world and, at the same time, of the controversial inner space of human beings which indeed evokes infinite extension and complexity as well. Human inner space is subject to the duality of instinct and reason or, as Mondrian put it, of the Natural and the Spiritual of which the opposite straight lines are a plastic symbol.

The uniform lines of NYC come into direct communication in BBW with fragments of the horizontal entering the vertical and vice versa. The univocal space of each single line of NYC, i.e., either horizontal or vertical, becomes a relational space where both opposite directions simultaneously coexist (BBW). The small square is the point in which an infinite and absolute space (the straight line) becomes for a moment finite and relative space:

We see in BBW a multiplicity of gray, yellow, red and blue little squares. To be precise, there are no yellow squares but only larger intervals of space between the gray, red, and blue squares. Yellow appears very rarely in the form of a small square and more frequently as a linear segment. This is why the lines of BBW appear mostly yellow.

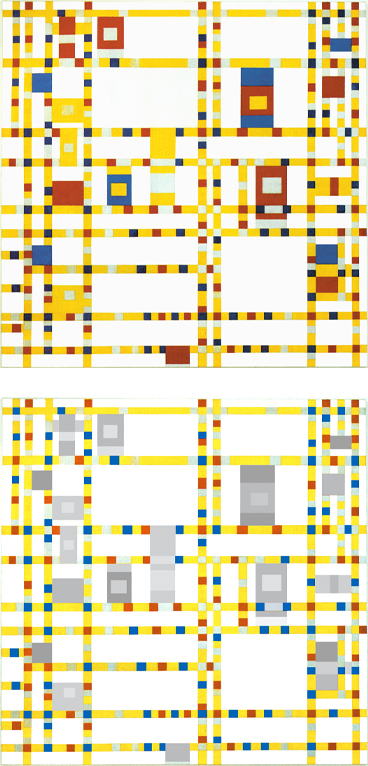

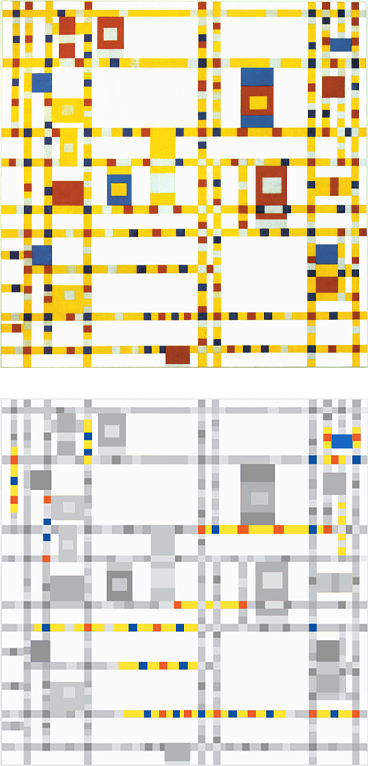

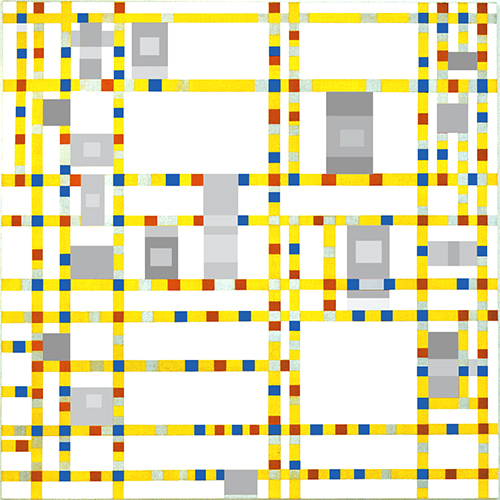

Diagram A

Everything seems to change incessantly in diagram A, where every point and every moment appear unique and unrepeatable, changing slightly in form when repeated in color and vice versa.

Closer examination shows indeed that the small squares present variable proportions, with some developing a slight horizontal predominance, some a vertical predominance, and some apparently attaining actual square proportions:

Diagram A

Every point lasts for just an instant before changing into the next point-instant. A space of this sort is well capable of representing both the changing variety of shapes that follow one another in the space of physical reality as well as a succession of impulses lasting only a few seconds within ourselves.

The dual and relative nature of the small square (split between horizontal and vertical), contrasts with the absolute nature of the single line (either horizontal or vertical) in which the small square finds itself here and there.

Moreover, the small square (a finite space) is placed under constant pressure by the dynamic and infinite nature of the line. It should be noted that these are two opposing tendencies of one and the same space.

The small squares are in a constant state of unstable equilibrium, continuously moving along the lines in the attempt to balance the momentary opposition between their horizontal part and the vertical line they become part of and vice versa.

Human beings too are part of an infinite space as the natural universe (evoked here by endless straight lines) and live a condition of inner duality always contended between instincts and thought or the Natural and the Spiritual, symbolized here, respectively, by the horizontal and the vertical.

It often occurs during our lives that internal imbalance generates external movement (action) and the attainment of a new internal equilibrium is then challenged by a new external situation in a constant dialectic between internal and external worlds.

What we shall observe from now on is an interaction between the tendency of the small squares to concentrate the infinite space of the lines towards a finite dimension, i.e., towards their own nature and a contrary tendency of the lines to expand boundlessly towards an absolute space (only one direction or the other). The small square strives to concentrate space upon itself so as to maintain balance between the two opposing directions it consists of. Think of the situations in our daily life when we try to achieve balance between the obstacles and the temptations of the external world and the integrity of our consciousness.

Diagram B

Observation of the frenzied succession of fragments reveals some that join up with others to generate some symmetrical configurations along the lines (Diagram B). The frenzied and ephemeral progression of different small squares along the lines is endowed with some constancy through the symmetrical sequences which present an orderly rhythm generated by a repeated alternation of same colors:

The symmetrical sequences highlighted in diagram B can be seen as portions of a regularly ordered and hence measurable space generated inside a virtually infinite and therefore immeasurable space like that of the straight lines, as though the space of the lines contracted for a moment into a finite segment (the symmetrical sequence) before reverting to infinite expansion.

The changing space of the lines – i.e. the ephemeral progression of different small squares – is endowed with greater constancy through symmetries. Human beings also endeavor during their lives to transform the variable flow of existence as far as possible into a more orderly and constant rhythm of foreseeable events.

The symmetrical configurations generate a dialectic between the tendency of the small squares to concentrate the infinite space of the opposite lines toward a finite dimension (i.e. toward their own nature) and a contrary tendency of the lines to expand boundlessly toward an absolute space (only one direction or the other). As mentioned, these are two opposing tendencies of one and the same space.

Careful observation of the symmetries formed on the lines shows that these are not wholly regular and precise geometric structures. While the alternation of colors is symmetrical, both the size of every small square and the space between them vary. We are thus faced with flexible symmetries under constant pressure from the dynamism of the lines. The symmetrical sequences should be seen in an elastic way as they seek to restrain and articulate the infinite space of the lines, which instead subject the concentration triggered by the symmetries to an expansive momentum.

An almost vertical relationship between two horizontal symmetries can be seen in the section of diagram B labeled 1. The relationship appears to be slightly staggered by the movement of the lines:

An analogous situation can be seen between two vertical symmetries at point 2, where a correspondence is now fully attained. Two vertical symmetries with a red center establish a horizontal symmetrical relationship between them.

Through the act of contemplating a horizontal relationship between two vertical symmetries (2), we actually generate a field of greater extension, i.e. a plane, which covers the space between the two vertical lines.

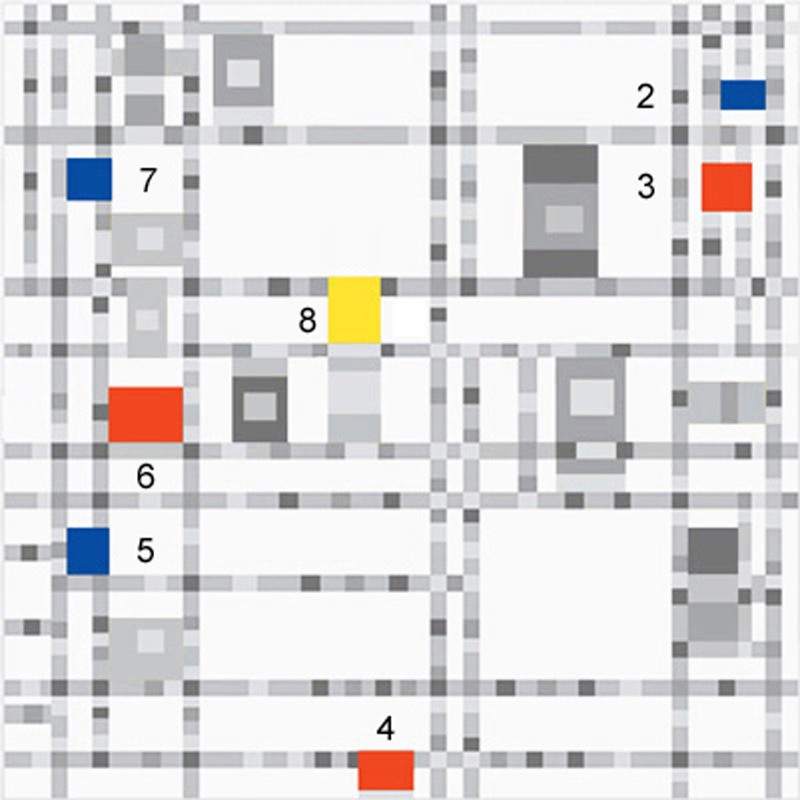

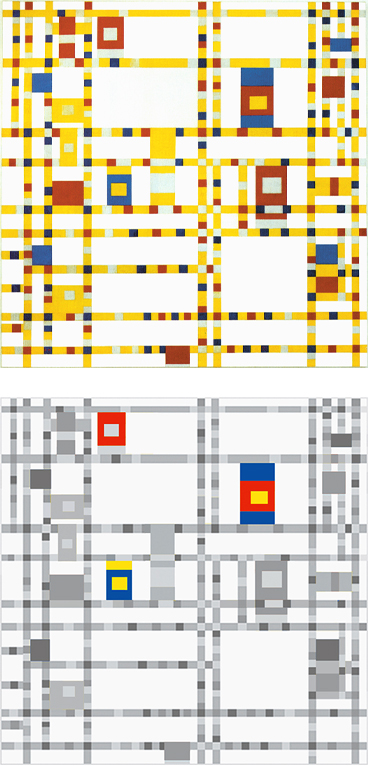

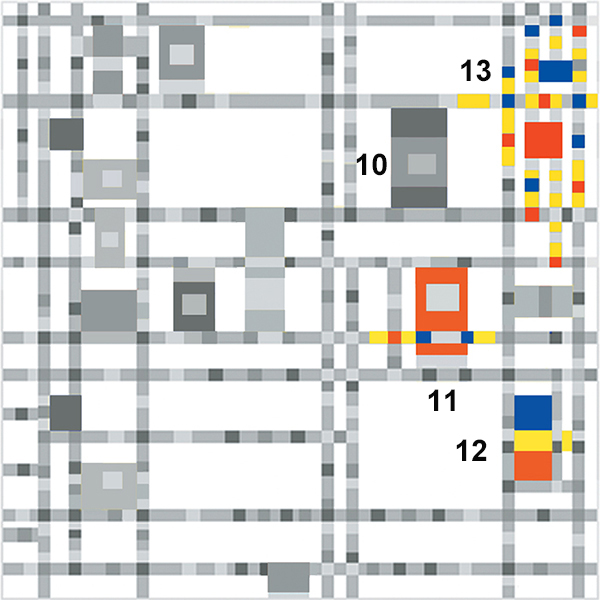

In that very point, we see the birth of a small blue plane and then of other planes which are being shown in diagram C:

Diagram C

Diagram C

Some planes undergo greater horizontal influence, some vertical predominance, and some appear to attain a relative condition of equilibrium between the two opposite directions. The relationship between horizontal and vertical lasts for a longer period of time in the more extended space of a plane than in the small squares inside the lines.

The contrast between the virtually infinite straight lines (exclusively horizontal or vertical) and the finite small squares (simultaneous presence of horizontal and vertical) ends up generating through the extended color planes a more stable balance between opposites.

Every instance of opposition can subsequently work in a broader context to generate a new and more stable balance. What appears negative today can become positive tomorrow. Our plans are sometimes obstructed by random and apparently extraneous factors that can, however, perform a useful function in prompting us to reformulate a project during its execution and ultimately improve it. The opposition of events should always be welcomed as an opportunity to adjust and develop the initial idea. In this way can equilibrium and dynamic unity be attained between the individual and the universal, subject and object, thought and nature. In everyday life, this presupposes a certain amount of patience, mental openness, and wisdom.

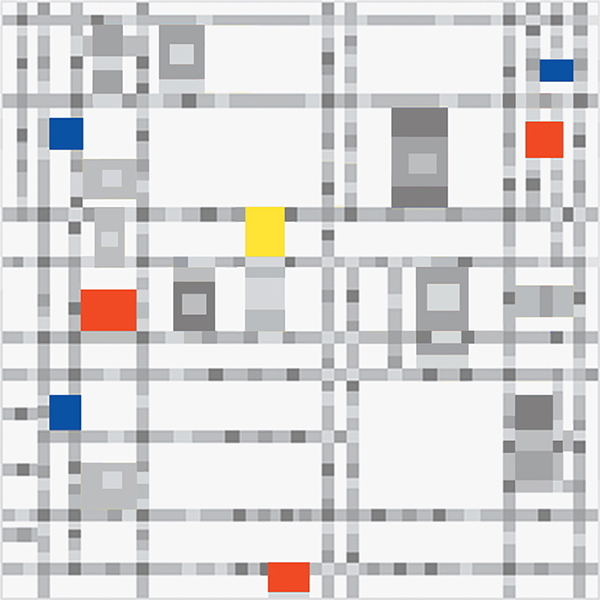

Diagram C: Some planes are still partially combined with the space of the lines (3), some are partially isolated (4, 5, 7) and some appear to be totally self-contained (6). The two planes 5 and 7 appear to be equal on first sight but closer observation shows that 5 has slightly greater vertical development:

As a whole, the planes indicated in diagram C represent a variety of different situations in a state of unstable equilibrium between horizontal and vertical, between yellow, red, and blue; a space of change but tending toward greater synthesis than its counterpart in diagram A.

Diagram D

To explain diagram D we start from diagram C: Plane 1 extends downward and drags with it a gray fragment of a horizontal line, which is transposed into the vertical and becomes a gray rectangular field inside plane 2:

Planes 1 and 2 should be seen as two successive moments in a dynamic sequence transforming a yellow plane into one made up of two colors (yellow and gray). If the painting is observed in a static way, the two planes are seen as a single vertical band. When viewed in dynamic terms, which is what Neoplastic painting demands, this band is nothing other than the transformation of plane 1 into plane 2.

New planes are thus born, as shown by diagram D, that differ from those observed in diagram C by presenting an inner space marked with a different color:

Due to the vertical predominance in plane 2, the internal gray band displays slightly greater horizontal development. Analogously, but in the opposite sense, the horizontal plane 3 is counterbalanced by a red vertical segment just as the red vertical predominance of plane 4 is offset by a gray horizontal segment. BBW displays continuous contrasting interactions between different parts.

If we see BBW as an abstract representation of our inner space, we can interpret the opposite lines, the small squares and the planes of different colors as symbolizing the multifarious and contradictory sides existing within us; the apparently irreconcilable aspects, just as apparently irreconcilable are horizontal and vertical in Neoplastic space.

Diagram D: Observation of the sequence 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 shows that the process of spatial internalization (beginning with 2) continues in other planes where the gray field, which is still open on the sides in 2, is concentrated and stabilized in the form of a small square within the respective yellow planes (5, 6, 7). A sign of linearity opposing the layout of planes 2, 3, 4 gives way to a more balanced configuration that reduces the opposition to the interior of planes 5, 6, 7.

Let us consider plane 5 in relation to plane 6. The former undergoes greater horizontal influence while the latter develops a marked vertical predominance.

The two internal quadrangles seem to reduce the imbalance manifested so obviously with the respective yellow parts of the planes. The internal quadrangles are the first timid sign (gray is the most tenuous chromatic value) of a shared inner nature that is more constant and detached from the frenzied and contradictory movement produced on the lines.

The lines can be regarded from now on as an external situation and the planes as the genesis and development of an internal condition of one and the same space that proceeds uninterruptedly from the outside to the inside.

We can interpret the transition from the frenetic and precarious space of the small squares to the more constant space of the planes (from an external to an internal space) as a plastic symbol of the gradual consolidation of our inner world through resistance to the conflicting pressures of the external world (symbolized in BBW by the opposite lines) and reinforcement of the equilibrium within by reaching a balanced synthesis of opposite drives.

Internalizing the exterior means opening up, going beyond the narrow boundaries of the conscious self and allowing this to be enriched as far as possible by the unpredictable development of life, not only in terms of outward reality but, at the same time, of inner life; the almost infinite reality that we bear within us and often find it difficult to decipher.

It means taking cognizance of the duality existing within us; understanding that our every act (thought or action) is the result of opposing drives, just as every small square or plane of BBW is born out of impulses that unavoidably undergo a vertical shift while intent on developing horizontally and vice versa.

Indian wisdom says that “the self is the friend of the self for those who overcome the self through the self.” Those who resist initial impulses and overcome situations of duality transform conflict with the oneself into synthesis and unity of being. At the same time, however, the process of growth and enrichment would not be possible without conflict and opposition.

Diagram E

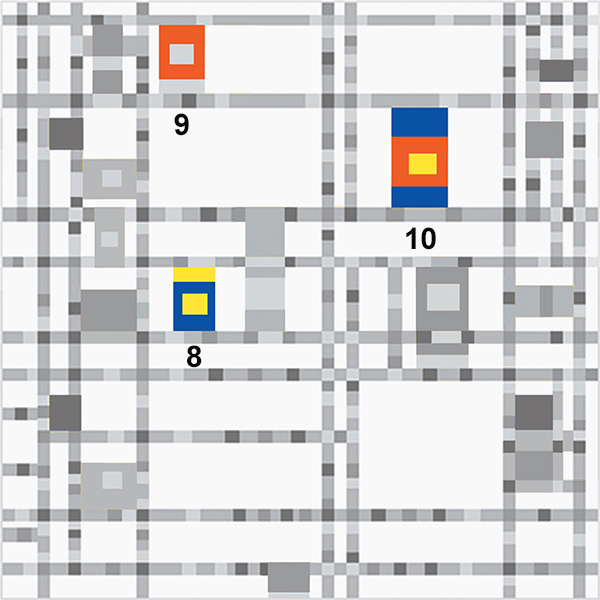

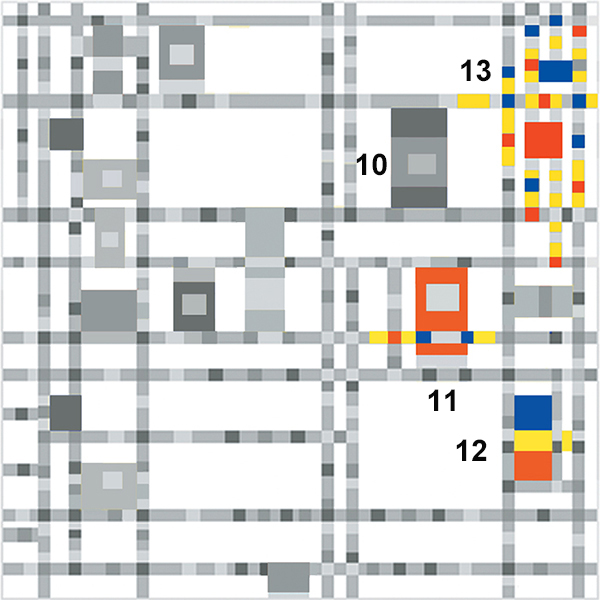

Diagram E shows how the self-internalization of space continues and there are now four colors concentrated in the area of just two planes: blue and yellow (8), red and gray (9) while a single plane expressing a synthesis of the three primary colors is finally reached at point 10.

The opposite directions colored yellow, red, and blue, which disrupted our visual field at the beginning of the process by keeping the eye in constant motion, attain unitary synthesis with plane 10:

Diagram E

Note how a quadrangle expresses equilibrium and synthesis of the opposing directions in the two planes 8 and 9 while a linear segment still opposes the field containing it. The segments inside the two planes 8 and 9 tell us that they are still influenced by the dynamism of the external lines in comparison with plane 10, which instead attains a self-contained and more balanced relationship between horizontal and vertical, external and internal space.

Though partaking of the interaction between opposites, this “vertical-horizontal” unity seems to resolve the opposition and contrast in felicitous equilibrium. The space of this plane expresses a comparative state of calm, albeit in an asymmetric and dynamic way, by comparison with the surrounding space.

It would, however, be a mistake to see this as calm in the sense of a total absence of inner tension. The unitary synthesis of BBW should rather be seen as a temporary equivalence of opposing thrusts that neutralize one another.

Any slight horizontal expansion of the yellow would produce an imbalance and set the mechanism of oppositions back in motion, as would even the slightest vertical increase in the blue.

While each color remains such, its size and proportions – and hence its value – depend on the proportions, and size of the other color. It is necessary to see the respective measures and positions of yellow, red, and blue give birth to a free interplay of reciprocal tensions. Every proportion depends on another in an unpredictable development of form that now depends directly on color, unlike the works produced between 1915 and 1940, where the colored planes were established a priori by form (the black lines).

In BBW the lines become planes and these concentrate into one plane. In the unitary plane the dynamic and virtually infinite space of the lines is transformed into a finite and lasting space. As mentioned, It would, however, be a mistake to see an absence of inner tension in the unitary synthesis of BBW. The dynamic nature of the unity is confirmed by diagram F.

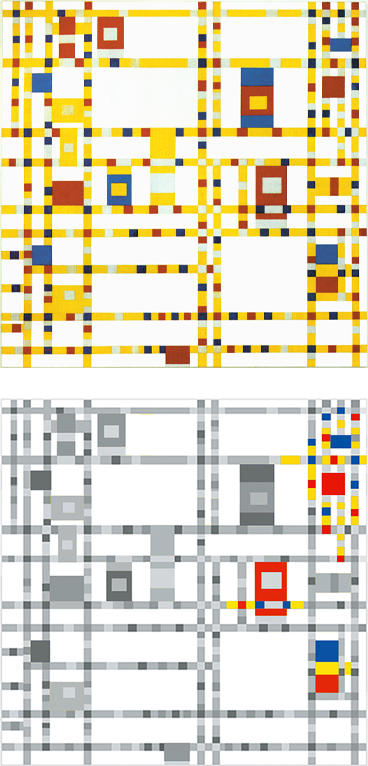

Diagram F

Plane 11 is the same size as plane 10 but consists solely of red and gray rather than the three primary colors. Moreover, the horizontal line running through the vertical plane tends to fragment the compactness of the unitary synthesis previously attained with 10:

Diagram F

After the equivalence of horizontal, vertical, blue, red and yellow attained in plane 10, the colors are again reduced in plane 11 and the external dynamism of the lines reappears to generate new contrast between opposites.

After the degree of comparative calm and unity achieved in plane 10, spatial movement seems to reappear in plane 11 which opens up to external space (the horizontal line crossing the plane), the colors are separated and flow back towards the more dynamic and variable space of the lines (12, 13).

The indication provided by plane 11 finds further confirmation in plane 12, where blue, yellow, and red are juxtaposed but no longer interpenetrate as they did in plane 10. The juxtaposition produces the impression of three separate planes, whereas the interpenetration combines the three colors in a single structure of greater stability. Note how the yellow on the right of 12 already seeks to cross the perimeter of the plane and flow into the yellow of the surrounding lines. Plane 12 can therefore be seen as plane 10 in the process of dissolution.

Diagram F

Configuration 13 possibly represents the conclusion of the process of reopening 10 in that it can be seen as a continuation of the disintegration of 12.

Space proceeds from a comparatively static and wholly internal condition (10) toward one of growing instability (11) that is gradually transformed into a more dynamic and variable external space (12, 13).

BBW shows a process where an expanded manifold space of yellow, red and blue fragments concentrate in one compact plane (Diagram E) which then reopens to a multiplicity of small colored fragments (Diagram F). From expansion toward increasing concentration and then from concentration back to expansion: this is the way BBW breathes:

Diagram E

Diagram F

The process which dynamically transforms multiplicity into unity is at the same time one of progressive internalization of external space (the lines, the small squares etc.) into several different planes and finally into one plane which unifies yellow, red and blue within itself and then reopens to the expanded external space of the lines. The color of the lines (external space) is yellow and yellow is also the color that is most internalized within the unitary plane.

“Through the internalization of what is known as matter and through externalization of what is known as spirit – until now too separate! – matter-spirit becomes a unity.” (Mondrian)

The artist identifies here the outer world as matter and the inner world as spirit.

Internalizing the outer means learning from one’s experience of the world. Externalizing the inner means taking cognizance of oneself and becoming aware of one’s real nature.

It is necessary to observe BBW in a state of dynamic equilibrium between one stage and another of the process highlighted above. We need to see the geometry in a state of becoming; to see the planes as they develop out of symmetries, and these while they are generated by the small squares, which arise in turn out of the interaction of opposing lines, each of which, taken in itself, expresses an absolute and infinite entity that eliminates any possible relationship, i.e. any possibility of space-time as we commonly understand it.

While we observe the finite fields of the planes, the lines continue uninterruptedly and the eye therefore finds itself in a state of unstable equilibrium between an extended space (symbolizing the incommensurable extension of the physical world) and the same space undergoing inward concentration (the relational and measurable space of thought evoked by the finite space of the planes).

Only through a dynamic process, multiplicity and unity become one and the same “thing” seen from opposite points of view. In this light, we can regard the unitary plane and the entire painting respectively as synthetic and as complex versions of one and the same thing.

I am thinking once again of the tree that looks like a condensed point when seen from a distance but reveals increasing complexity on closer observation. Each single thing and every aspect of life can unveil the one and the many. How to achieve this if not in abstract terms?

This way of seeing calls into question the position of the observer with respect to the thing observed and thus the movement of the subject with respect to the object. Movement should be understood here not only as moving through physical space but also in mental space, that is, as reflection and deepening of a specific aspects of reality. This was precisely what Mondrian reproached the Cubist painters for, namely, not having drawn the consequences of their first approach to the question of a dynamical representation of reality.

Nature and life still remain the primary source of inspiration for abstract art. The enchanting fragrance and the incredible wealth of forms that nature offers to our gaze. The ten thousand different things that we see around us prove on closer examination to be a single interminable line, because in nature everything is different, manifold, infinite, and at the same time one.

Everything is one just as every individual thing is a complex set of parts. Modern technology reveals that the apparent simplicity of a leaf is a small universe and that the immensity of earthly nature is a bluish-white spot in the infinite space of the macrocosm. The immensity of earthly nature is as simple as a leaf, which is as complex as the entire planet. Multiplicity becomes unity and unity reveals multiplicity. This is what Broadway Boogie Woogie shows us.

Though aware that the reality is far more complex, we often tend to make narrow, summary judgments. The reality before us is always more complex than our descriptions but we cannot always concentrate on it and investigate every single aspect in depth, not least because every single aspect is in fact an infinite reality in itself. This has always been true and is even more so today given the level of complexity attained by modern societies.

I therefore believe that the question of the one and the many is one of the most relevant to the present day. Nor is this something purely intellectual. We often experience a drive for concentration when rational explanations give way to an urge that transforms all the complexity and fragmentation of a vision thought into the almost absolute synthesis of a vision felt. When we fall in love, for example, the whole of our fragmented daily life seems to come together in a concentrated form of energy that makes us feel in harmony with the world.

Recap

From a multiplicity of small squares (Diagram A) come symmetrical sequences (Diagram B) which in turn give birth to various planes (Diagram C and D) that finally become one single plane which expresses a synthesis of the whole composition (Diagram E) and then reopens to a multiplicity of small squares (Diagram F):

Space undergoes gradual transformation from the condition of lines, an infinite and absolute space (either horizontal or vertical), to the condition of planes (a finite and relative space).

As mentioned, the lines can be regarded as an external situation and the planes as the genesis and development of an internal condition of the same space that proceeds uninterruptedly from an outer (Diagram A) to an inner space (Diagram E) and from the inner to the outer (Diagram F):

A multiplicity (Diagram A) turns into unity (Diagram E) which then reopens to multiplicity (Diagram F). It is a philosophical issue: Multiple and one, particular and universal, traditionally considered opposite terms, become the same “thing” seen from different points of view. We shall return to this.

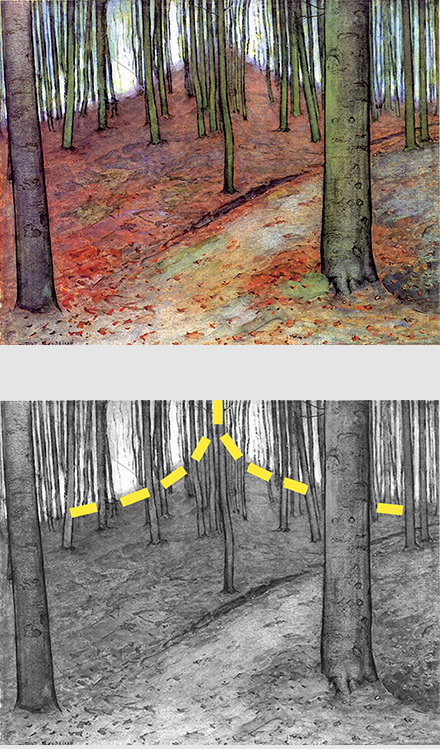

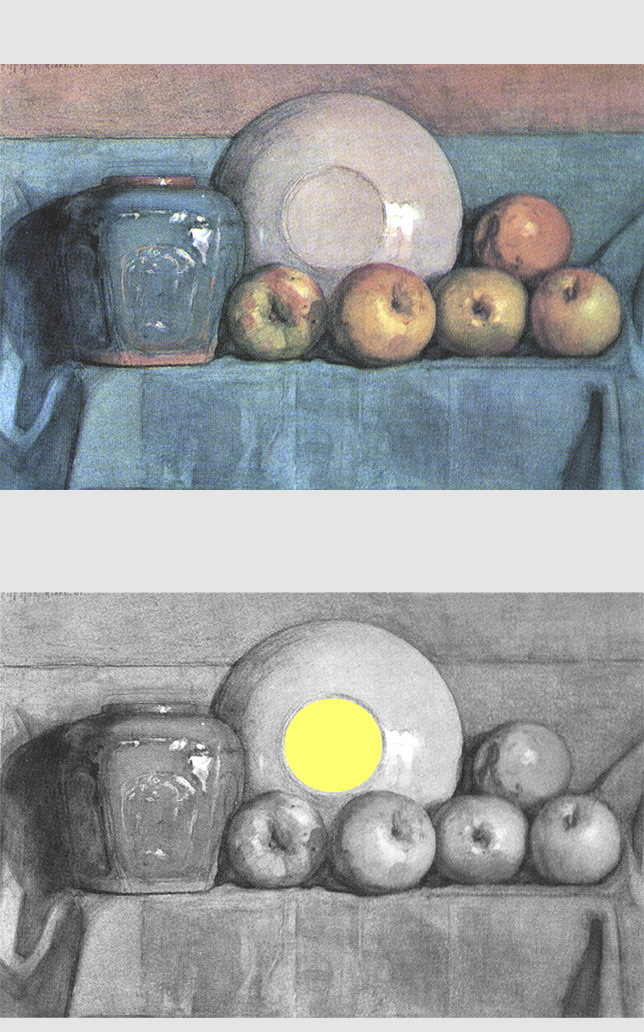

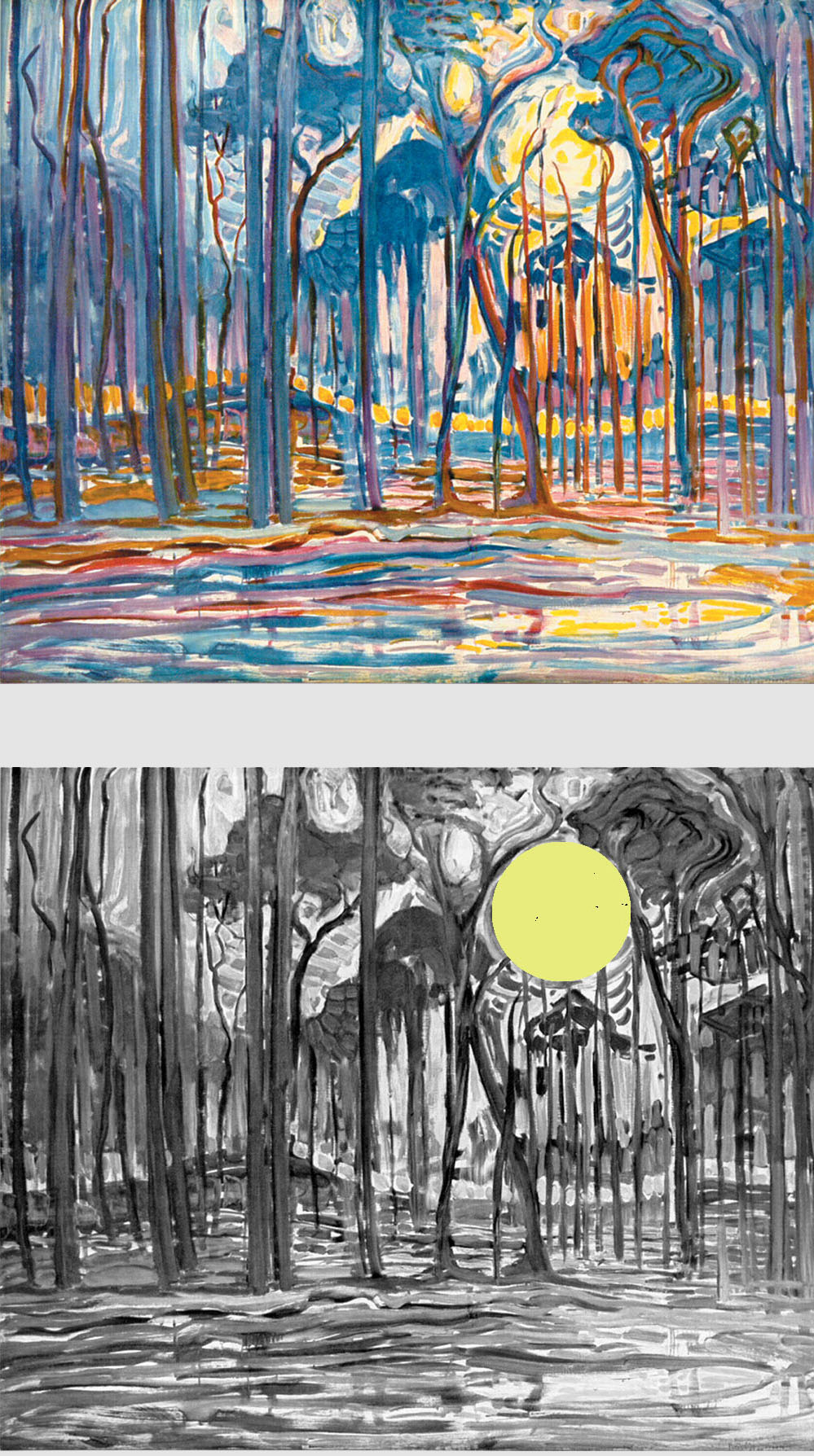

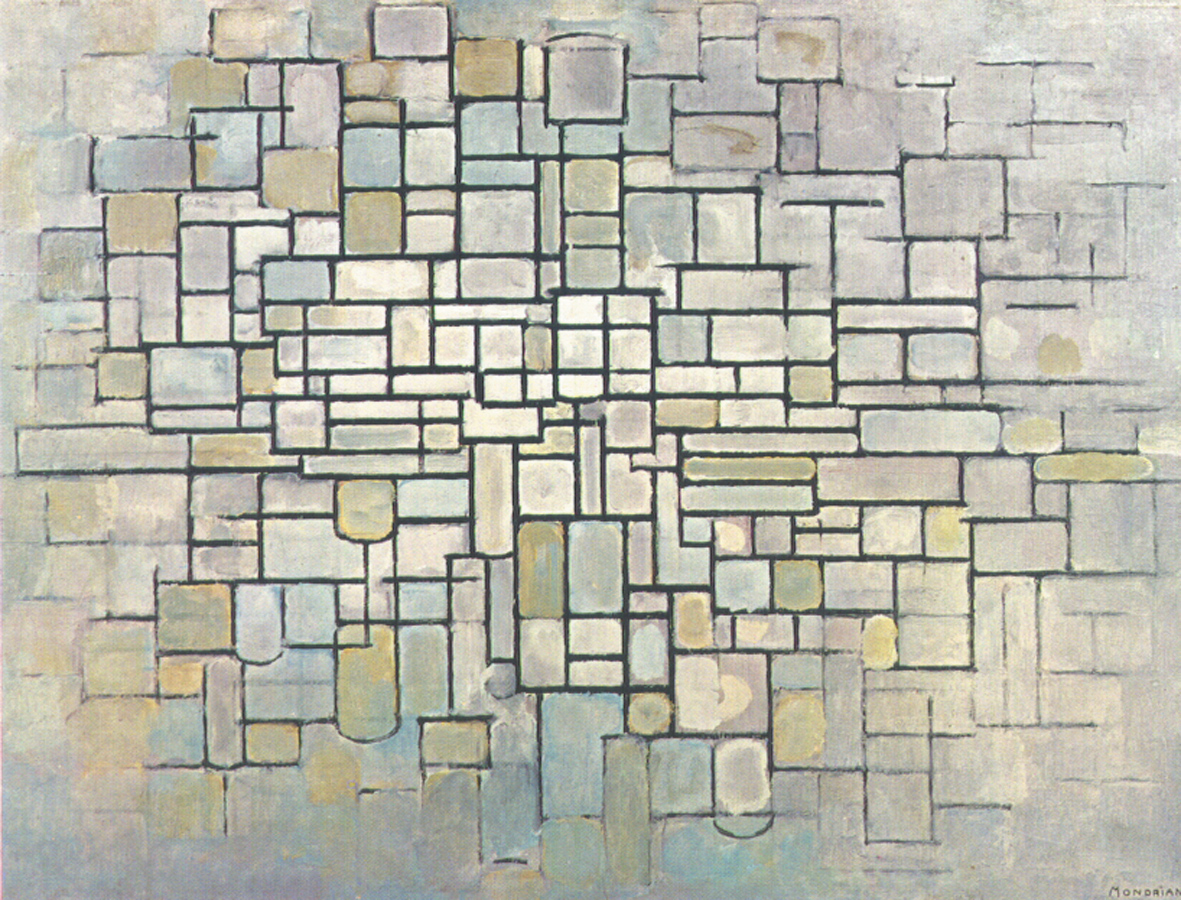

The relationship between multiplicity and unity has been the guiding thread of Mondrian’s entire oeuvre since the first naturalistic works:

throughout the Expressionistic phase (1907-1910):

and the Cubist compositions (1911-1915):

up to the whole Neoplastic works (1919-1942):

I am reminded of the scattered rectangles lacking unity of (Fig. 7) which try to reach a synthesis in terms of color by means of three superimposed squares (Fig. 8).

I as well think of a white rectangle in the center of Fig. 9 suggesting an ideal synthesis of three surrounding colored rectangles and the attempt to attain unitary interpenetration of the white rectangle and the colored rectangles in one large colored square form (Fig. 10):

A synthesis of horizontal, vertical, yellow, red and blue is then finally achieved with great visibility twenty-two years later in Broadway Boogie Woogie:

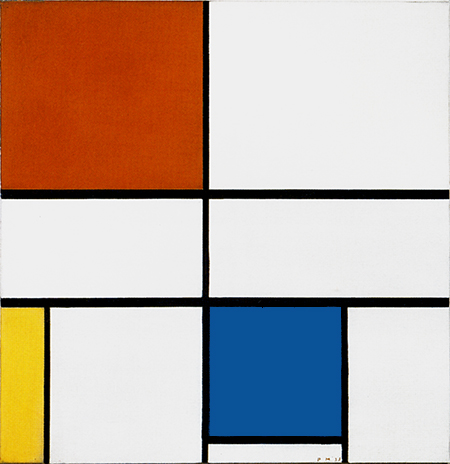

Diagram E

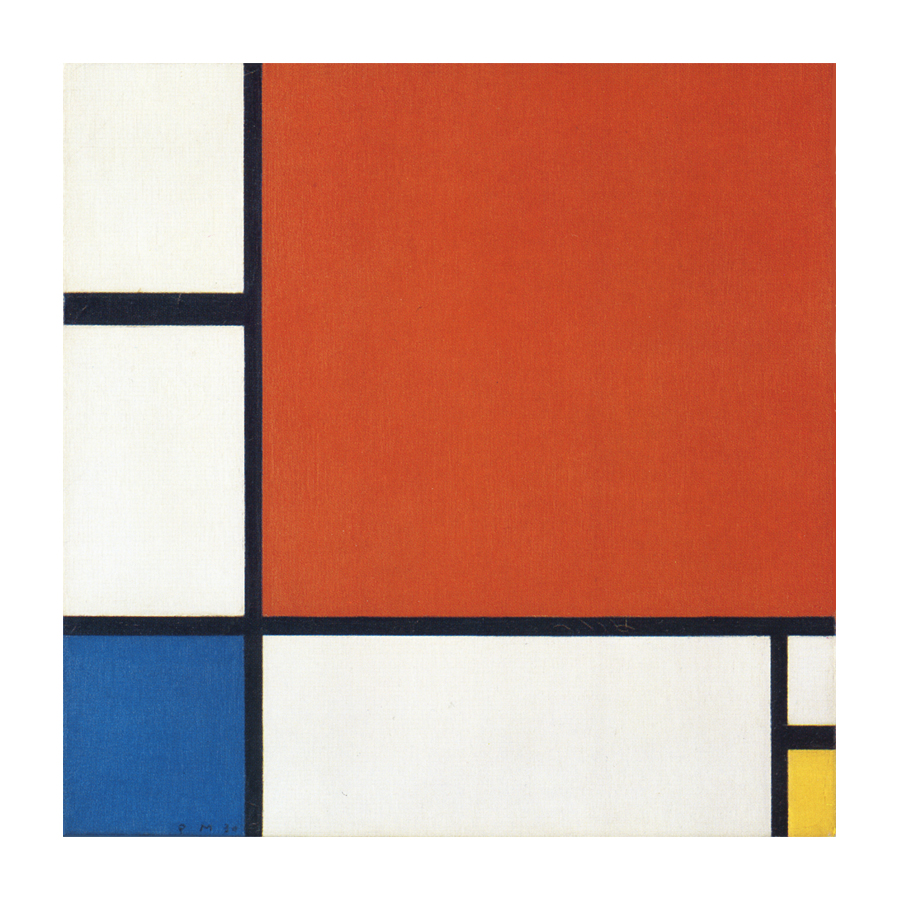

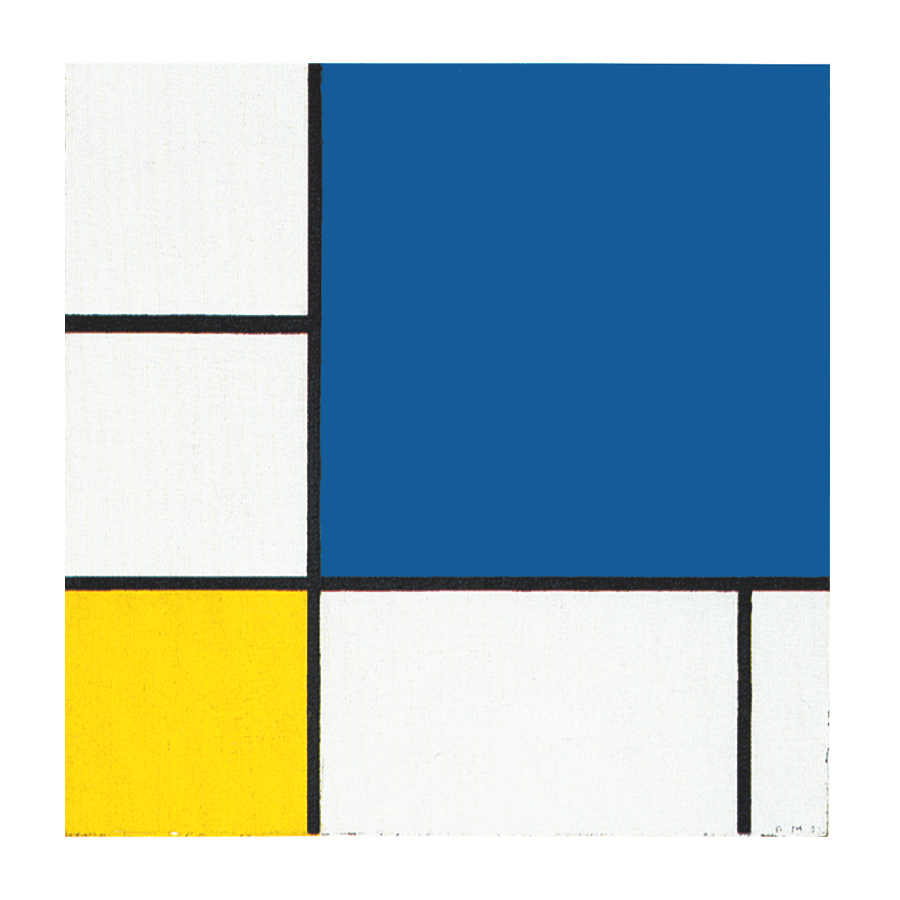

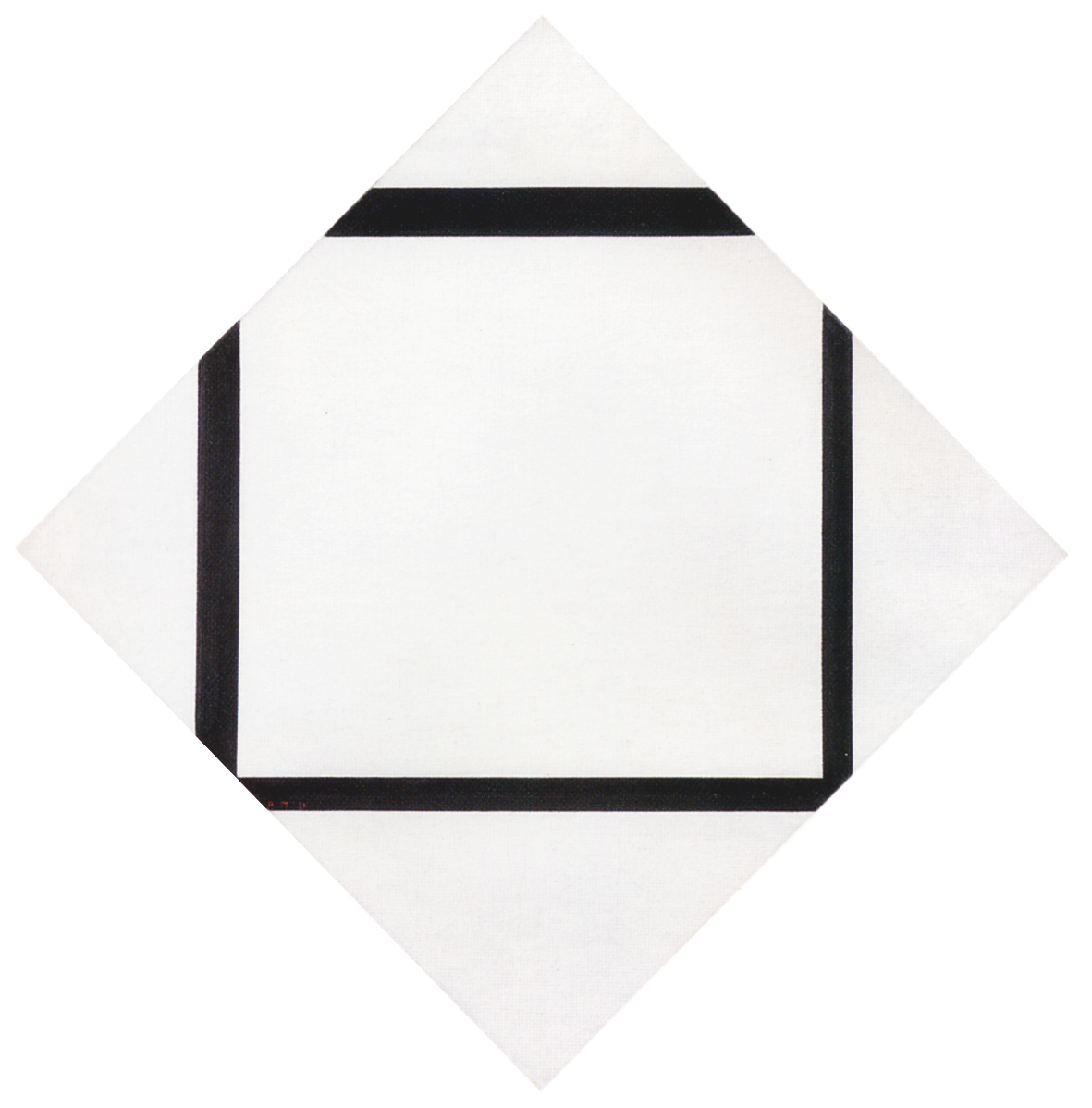

In Mondrian’s last accomplished painting, for the first time, the unitary synthesis is no longer suggested by a blue, a yellow or a red square (Fig. 11 and Fig. 12) or by a white square marked out with black lines (Fig. VII) or yellow lines (Fig. 13), but with a simultaneous concentration of yellow, red, and blue; a free and unpredictable interplay of form that depends directly on the respective qualities and quantities of the colors.

Composition en Rouge, Bleu et Jaune

1930

Composition with Blue and Yellow

1932,

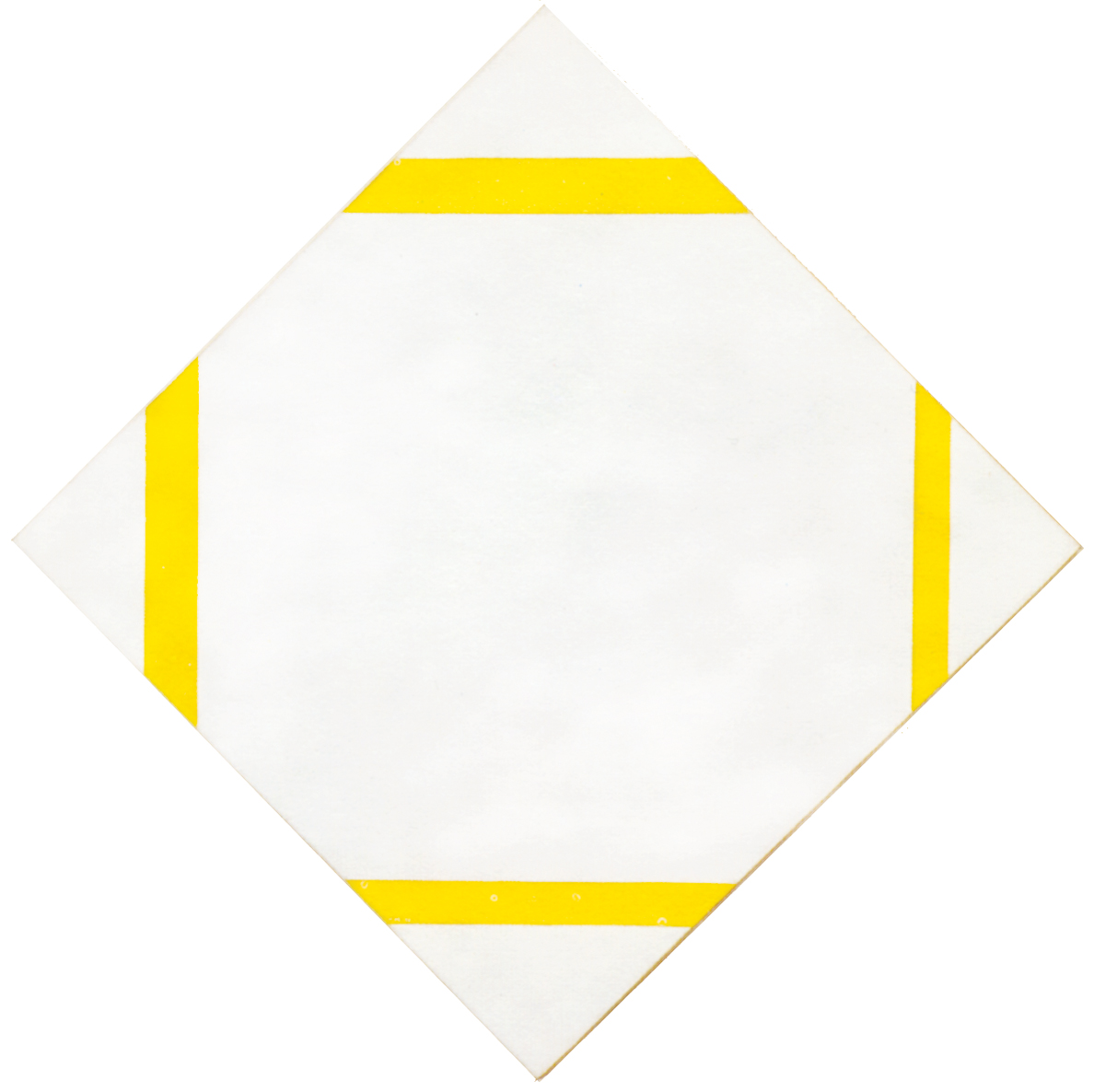

Lozenge with Black Lines

1930

Lozenge with Yellow Lines

1933

The equilibrium attained in the unitary plane of Broadway Boogie Woogie is dynamic in nature and not the result of an approximate equal amount of horizontal and vertical represented by the square module we have seen from 1915 on. While it is true that the artist had always made flexible and dynamic use of the square form, it is equally true that the square dominated the evolution of Neoplastic space in certain phases, at least up to 1933 (Fig. 14).

The square form served Mondrian from 1915 to the mid-1930s as a sort of cornerstone or starting point to open his compositions up to change. At the end of this process, his space was asymmetric and colored all the way through, simultaneously multiple and unitary (Broadway Boogie Woogie).

No premeditated design

The process I have pointed out in Broadway Boogie Woogie might make one think of it as the result of a premeditated design. After reading the explanations provided above, some will indeed wonder whether Mondrian actually thought of the image in the way described here while painting it. We would have to ask the artist himself, but I think I can safely say that the answer would be: No.

The process observed in Broadway Boogie Woogie is not the result of a plan of the moment. This is a work constituting the compendium of an entire life, an image in which the artist finally succeeds in adequately expressing the immense variety of the world along with the synthesis he had always sought within himself. A world which was rapidly changing and therefore demanding new ways of visual representation. Reconnecting the outer world with the inner world was the purpose of the Dutch artist’s entire life.

I believe that Mondrian gave shape to the composition in a spontaneous and intuitive way, adding, removing, and modifying the parts in no precise order. I do not believe that the artist ever consciously visualized the process showed in Broadway Boogie Woogie even after finishing the work. In his interview with J.J. Sweeney in 1943, he declared his inability to express what he was doing with sufficient clarity.

Mondrian did not conceive Broadway Boogie Woogie in the way it is explained here. He painted it, and for a painter, for a true artist, painting is equivalent to thinking. The reflections and explanations come only later, if at all, when it is all over and done with. A true artist is wholly involved in the intuitive interplay dictated by the eye and not in reflective reasoning.

Consider a yellow line that continues uninterruptedly and a red small square inside it. When the painter adds one and then another small gray square that work with the red to form a symmetrical configuration, he is not thinking about its conceptual meanings. His eye delights in seeing the brighter contrasting colors take on a measured form and an appropriate proportional relationship. Mondrian sees the line expand and the small square give birth to a movement of concentration. There is no need to think. The painter sees and what he sees goes straight to the heart. This is how I believe he worked, the way a true artist works.

Cézanne: “If one feels in the right way, one will think in the right way. Painting is first of all a way of looking. The subject matter of our art is there, in what our eyes think.”

Processes such as the one observed in Broadway Boogie Woogie can certainly not be thought out but only carried through, step by step, following our intuition. If your intuition reaches such depths and succeeds in seeing so far, the results acquire all the astonishing and organic coherence that, it should be recalled, is displayed only upon completion. It is easier for us today to see the entire work as a whole.

It was certainly impossible for the painter to take full cognizance of everything he was creating when he let himself be guided by his eye in addressing the canvas with his brushes. At the end of his life Paul Cézanne wrote, “I think in the end we will be of no use.” This is the spirit of the great ones, never really aware and satisfied with their achievements.

A flexible geometry

Mondrian’s pictorial evolution shows that, contrary to common belief, the artist had no intention whatsoever of forcing nature and human existence into rigid geometric schemata but rather of making his geometry as open and flexible as possible. In Broadway Boogie Woogie every form is born, grows and develops as every natural form does. As in natural space, nothing lasts forever; no entity is pre-established but becomes such in that particular situation, in that particular positional relationship with respect to the other forms undergoing reciprocal determination.

Every point of Broadway Boogie Woogie is unique and unforeseeable but, at the same time, part of a process that brings all of the elements together into a universal rhythm. A fluid space that gives concrete form to becoming more than being, to relations more than the individual things; a geometry that is anything but rigid, cold, or exclusively rational; a space that strikes me instead as very similar to life.

I believe that Neoplastic geometry has very little to do with the rather aseptic geometry of certain form of abstract concrete art in the second half of the 20th century.

Dancing was Mondrian’s favorite pastime. The Dutch visitors knew it well. To really please him, after a good meal, he had to be taken to a “distinguished” dance hall. I must confess that, not being a dancer myself, it took me years to understand that he took dancing very seriously. Even in 1930, the dance exhibitions that he sometimes made in his studio, in front of a small gramophone painted in red, were for me derisory spectacles. When some Dutch people wanted to invite me to one of these “urf” clubs, I suffered all evening to see Mondrian dancing.

It seemed to me (I was certainly wrong) that he danced very badly and I felt sorry for the women he invited. In 1932 he told me that he couldn’t go to a group meeting because he had a dance class that night. I thought he was finally learning to dance. He was sixty years old! I was to learn much later that already in Laren, in 1916, he went dancing every Sunday. He chose the prettiest girl,” a witness of the time, Mr. van Tussenbroeck, told me, “and danced as stiff as a candle, with his head in the air, without saying a word to his partner.

Michel Seuphor, Piet Mondrian, Sa Vie, son Oeuvre, 1956)

A misleading title

I think it necessary to say a few words also about the title Mondrian gave this painting. It may have been as a tribute to the place that offered him a home, as he had already paid tribute to Paris with a work entitled Place de la Concorde and to London with Trafalgar Square. The title has, however, given rise to no small number of misunderstandings by suggesting superficial parallels with the outward appearance of New York City.

Broadway lights?

The painting obviously has very little to do with the lights of Broadway, the skyscrapers, the traffic or the street plan of Manhattan. If we really want to stick to the city where the image took shape, we could if anything think in terms of its pulsating rhythm, of the contrasts, the constant movement, the infinite variety of humanity, situations, and disparate elements that make up New York City.

An image of music?

I would attach little importance to any direct links with boogie-woogie music, which the painter certainly loved. He pointed out in his interview with Sweeney that he saw true boogie-woogie “as harmonizing in intention to his own aim in painting: the destruction of melody, which is equivalent to the destruction of natural appearances, and construction through the constant opposition of pure means: dynamic rhythm.”

Always keenly aware of the educational function of art, Mondrian used an analogy with boogie-woogie, as earlier with the fox trot and jazz, to suggest a parallel helping us to understand plastic expression at a different level from the image, with a language, i.e. that of music, which is perhaps the closest to Neoplastic painting, since music has been expressed in abstract terms from the very outset. I do not believe, however, that Mondrian ever intended with Broadway Boogie Woogie, as with other works of his, to give pictorial form to a certain type of music, or indeed that music was the primary source of inspiration for his compositions.

What the fox trot or boogie-woogie may have in common with Mondrian’s paintings is the fact that both music and images tend to create dynamic sequences. The analogy with music must, however, serve toward the full understanding and enjoyment of painting.

A true critic?

No, Broadway Boogie Woogie is not to be understood through reference to its title. The substance of things lies and remains wholly in the visual data. Those capable of seeing in the painting only what the title suggests to them, will have to wait until their vision becomes more finely honed and reveals the deeper reality, which lies always and exclusively in images and not in words, at least in the case of the visual arts.

As Mondrian observed, “A true critic can, simply by drawing upon the depths of his humanity and observing with purity, write about the new forms of art even without a knowledge of the working technique (…). But a true critic is somewhat rare.”

Where is the edge?

North American critics often describe abstract art and especially the type involving precise, clear-cut shapes by means of the term “hard-edge”, as though we were talking about the outer aspect of some object. The value of Neoplastic visual thinking lies instead precisely in the abolition of every particular form in favor of the expression of pure relationships. The measurements, proportions, and chromatic or tonal variations in Neoplastic compositions are not pre-established but generated out of one another through reciprocal influence.

The squares are never really such because it is the eye rather than mathematics that decides on their proportions; their extension can be slightly more vertical in some cases and horizontal in others depending on the spatial context in which they are developed. There are no elements in Neoplastic space endowed with absolute validity other than the perpendicular relationship and its infinite possible variations.

The synthesis of an entire life

After forty years of patient work, the one and the many – respective symbols of the Spiritual and the Natural – are now expressed in a sharp and bright form. Fundamental issues of Mondrian’s visual thinking have remained the same throughout his life while there has been a drastic change in the plastic means serving to give clear shape to a new vision of reality which has finally found a sharp and bright form with his last accomplished painting.

The process observed in Broadway Boogie Woogie condenses the whole of Mondrian’s oeuvre within one canvas. Between 1913 up to 1943 we in fact see space evolving from rich and complexed compositions:

to very synthetic compositions; that is to say from a multiple to a unitary space:

and then we see space reverting from unity back to multiplicity:

A pathway that stretched over some twenty-two years can be found encapsulated in the process observed in Broadway Boogie Woogie where the multiple space of lines and small squares concentrates into a unitary plane which then reopens to a multiplicity of small squares and lines. This canvas sums up an entire life and it is perhaps no coincidence that this was the last work completed by the artist.

Life is a continued examination of the same thing in ever-greater depth” (Mondrian)

Next page: Neoplasticism – Part 7

back to overview

Copyright 1989 – 2025 Michael (Michele) Sciam All Rights Reserved More