Please note: If on devices you click on links to images and/or text that do not open if they should, just slightly scroll the screen to re-enable the function. Strange behavior of WordPress.

The interpretation of the visible

We begin this page with some basic historical information about Impressionism, Expressionism and the work of Cézanne.

Impressionism

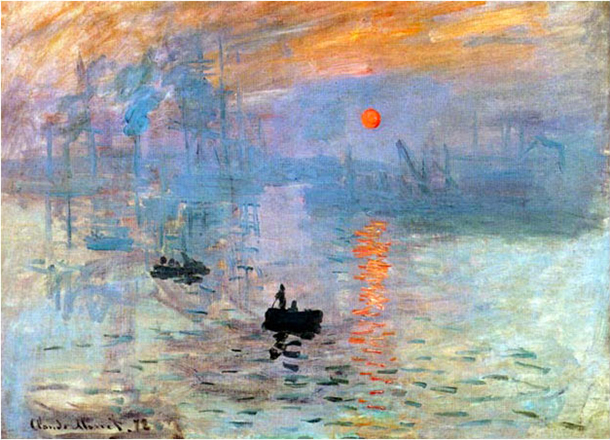

In 1872 Claude Monet painted a canvas depicting a harbor at dawn and entitled it Impression Soleil Levant.

Oil on Canvas, cm. 48 x 63

It was a landscape rendered almost instantaneously, as though the painter had been intent on capturing a reality that would soon change. The term “Impressionist painters” derives precisely from this canvas, which was the object of a hostile review accusing the artist of shortcomings in finishing, draftsmanship, and the handling of detail.

The official culture of the time preferred an art rich in academic virtuosity and designed to celebrate life in the showy aspects that appealed to the upper classes. These young painters instead dared to paint everyday life rather than the heroic deeds of established historical figures that no longer had much to do with real life.

Everything began to change in human life halfway through the 19th century with the process of industrialization and its attendant social transformations, the advent of photography, a magical device making it possible to “paint” a scene in real time, and the increase in the speed at which people traveled and perceived the world around them. The Impressionist painters shared the perception of a reality undergoing transformation and introduced this sense of the flux and change of life into their canvases. The focus was not on immanent and lasting aspects but those of a fleeting, everyday nature.

In 1893 Monet painted several versions of the façade of Rouen cathedral at different hours of the day, with the appearance of the solid and imposing edifice altering in relation to the light of the moment.

Expressionism

Few years later color and sign acquired an autonomous role designed to express the feelings of the painter beholding reality.

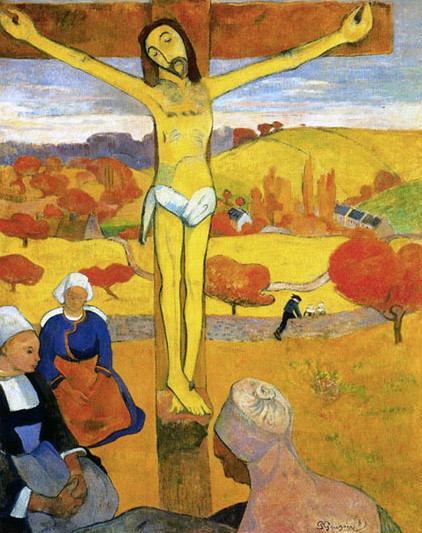

Paul Gauguin painted a crucifixion with a yellow Christ and red trees in 1889:

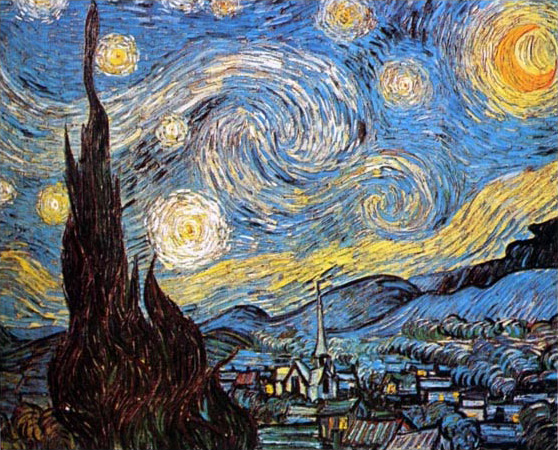

In the same year Vincent Van Gogh painted a starry night with every star as a vortex of light and energy pervading all the heavens. Landscapes were no longer painted in the way they appeared but rather as the artists saw them or indeed felt them inwardly.

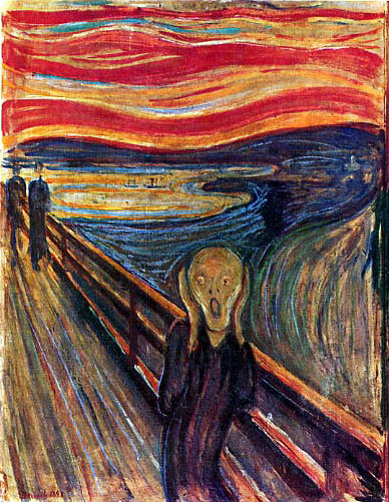

Edvard Munch painted a human figure screaming from a bridge. The external space is pervaded by that scream, which is propagated all over the surface of the painting in sinuous lines. The sky as a whole is transformed into a scream, which becomes a high-pitched shriek with the use of red. The artist’s inner world pervades and modifies the usual appearances of the outer:

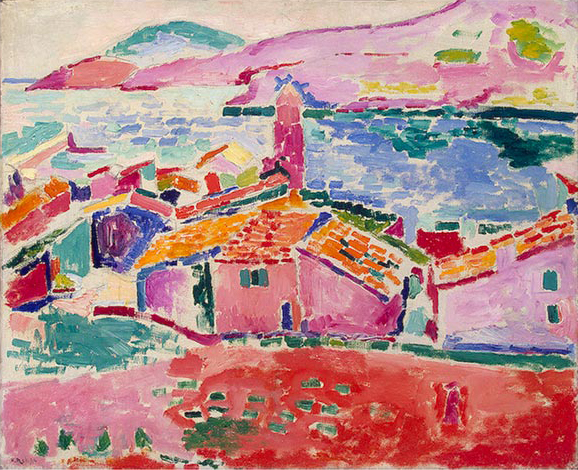

In the wake of the Impressionist painters, Seurat, Signac, Matisse, Derain, and De Vlaminck accentuated the use of color still further, again provoking indignant protests on the part of a critic, who was to describe them as “fauves” (beasts).

“I can bring together the armchair beside me in the studio, the cloud in sky, and the rustling leaves of the palm by the water’s edge with no effort to differentiate the places and without dissociating the different elements of my motif, which are all one in my spirit.” (Matisse)

Outer reality is constituted and assumes meaning in the inner space of consciousness. While this has obviously always been true and is a fact implicit in every human activity, the painters most sensitive to the new developments at that time appear to have focused on this fundamental truth.

Cézanne

While Monet’s addressed the light enveloping and molding everything, Cézanne sought a more solid structure of space capable of expressing change but also a certain sense of duration and permanence at the same time. As he put it, “Nature is always the same, but nothing remains of it, of what appears. Our art must give the shiver of its duration and enable us to appreciate its eternity.”

Cézanne wanted to find some indication of greater constancy among the changing appearances of the external world. “Everything in nature is modeled on the sphere, the cone, and the cylinder. We must learn to paint in these simple figures. Later on it will be possible to do whatever you want”.

He searched for a way to reduce the immense variety of the world to a common denominator and suggested, purely as a preliminary measure, that nature should be seen in terms of the elementary forms of the sphere, cone, and cylinder. He needed to find a solid basis from which to address the changing variety of appearances.

Faced with a reality that was multiplying its appearances at the end of the 19th century, Cézanne strove to concentrate and unify. His work endeavors to abolish the perspective illusion of the third dimension by integrating the different planes into one plane. Objects and space tend to interpenetrate; solids and voids acquire the same value.

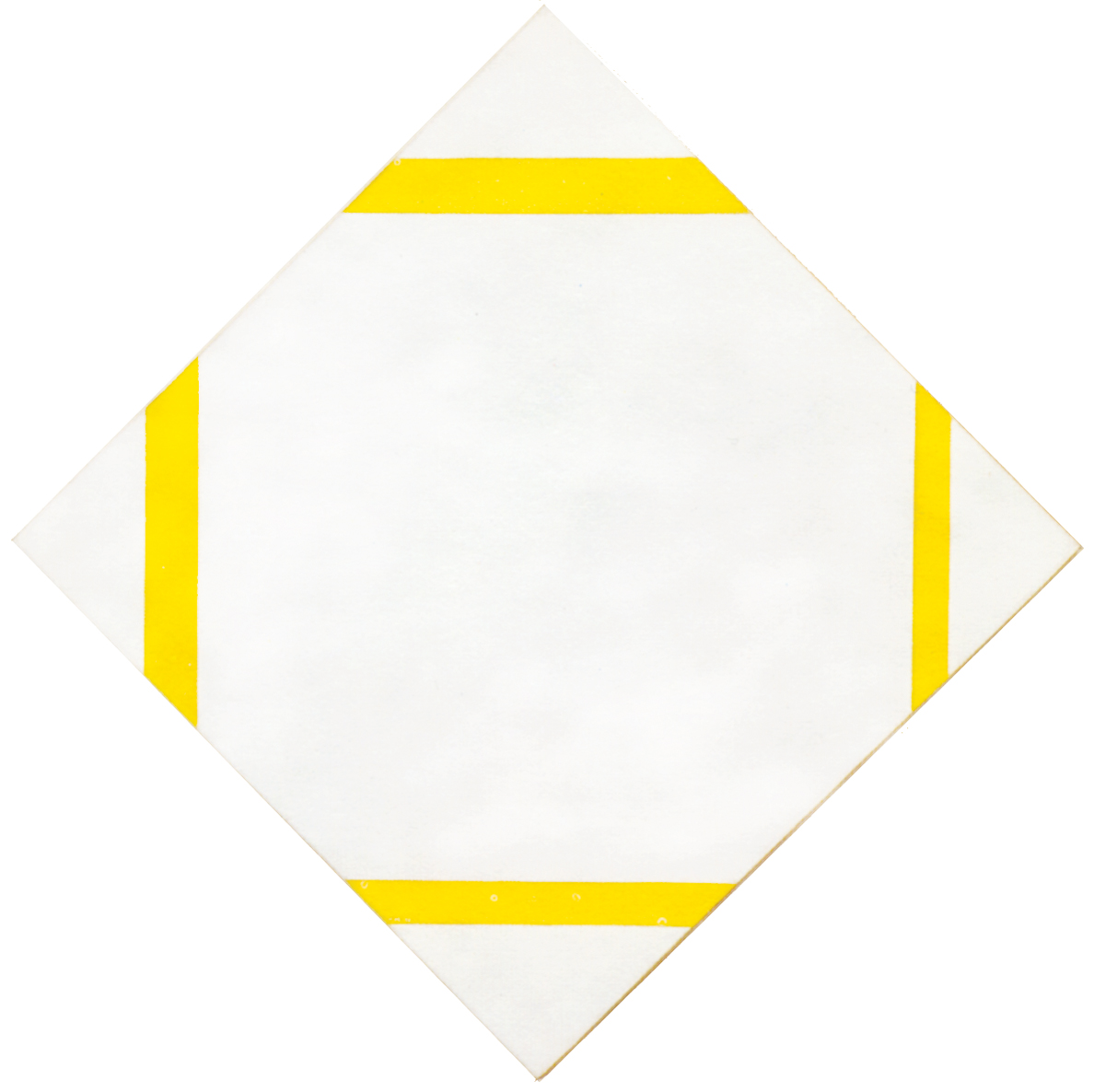

Mondrian

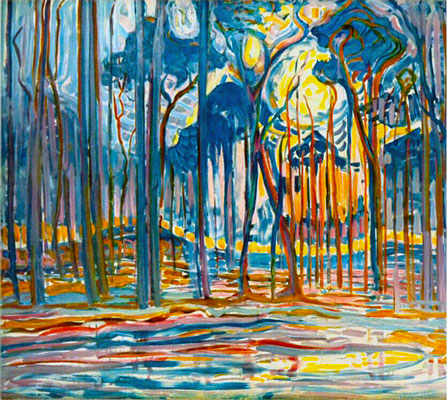

In the wake of the so-called Dutch luministic painting, as well as the work of Vincent Van Gogh and the Fauves painters, Mondrian begun around 1907 to use brighter colors corresponding more to his inner vision rather than the more immediate appearance of things. In this respect we talk about Mondrian’s Expressionism although there are significant differences between Mondrian and, for instance, the German Expressionism.

In 1908 Mondrian paints a wood at the base of which a river seems to flow. The whereabouts have been located in the vicinity of Oele. The wood has none of the colors one would expect to see in nature. Greens, browns, and shades of ocher give way to blues, reds, and yellows that generate a dynamic space evoking the intense emotions aroused in the artist by nature. The tree trunks become quick vertical lines contrasting with the horizontals of the ground and of the river:

Oil on Canvas, cm. 128 x 158

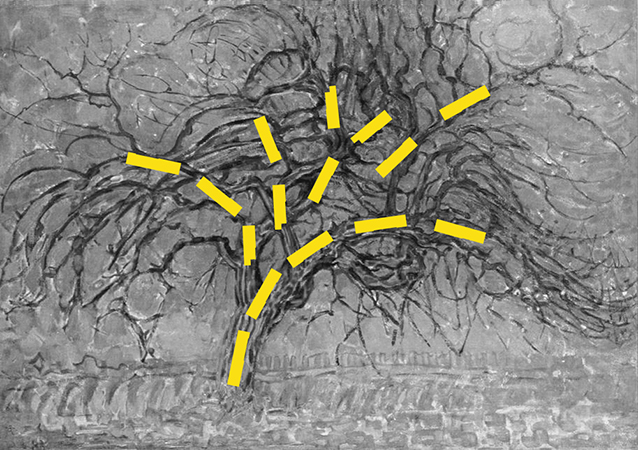

The opposition between horizontals and verticals generates in the background a sinuous horizontal line (highlighted with yellow dots) whose winding horizontal course seems to absorb the vertical thrust of the trunks. In the upper section the arched form of some trunks is concentrated in the circle of a sun, suggesting a synthesis of vertical and horizontal.

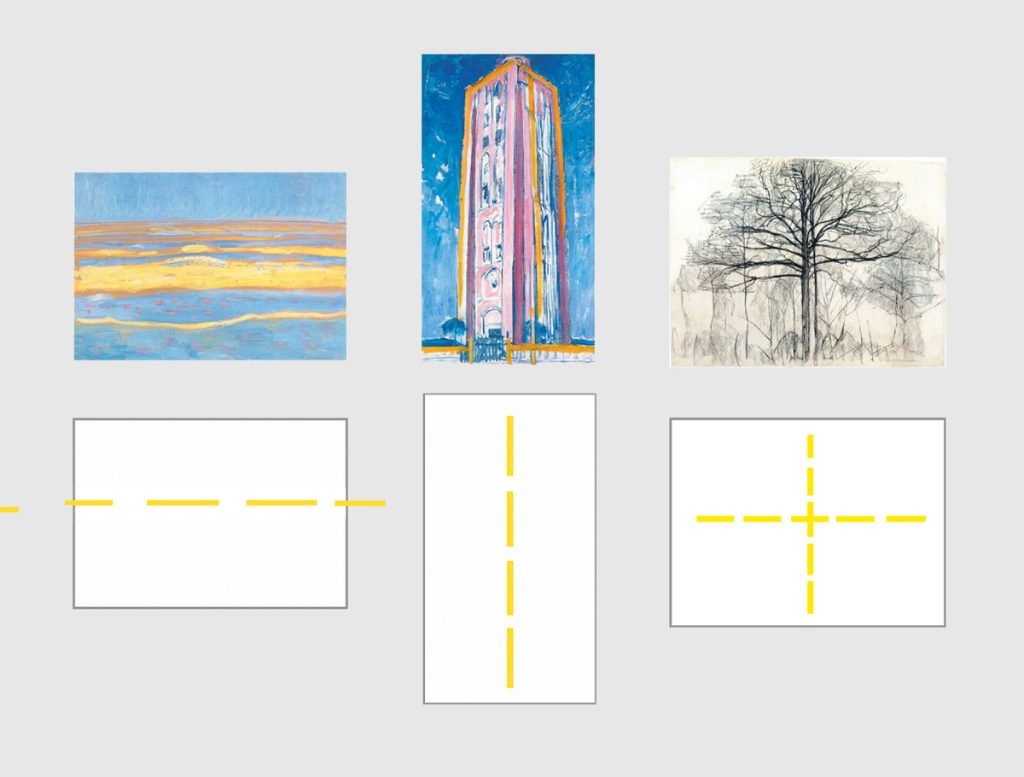

Mondrian was intent at that time on expressing strong contrasts, not only with a marked accentuation of color but also with a gradual orientation of his compositions more toward a decided opposition of horizontal and vertical lines within the same canvas or through the alternation of canvases showing a predominant horizontal an all-vertical space.

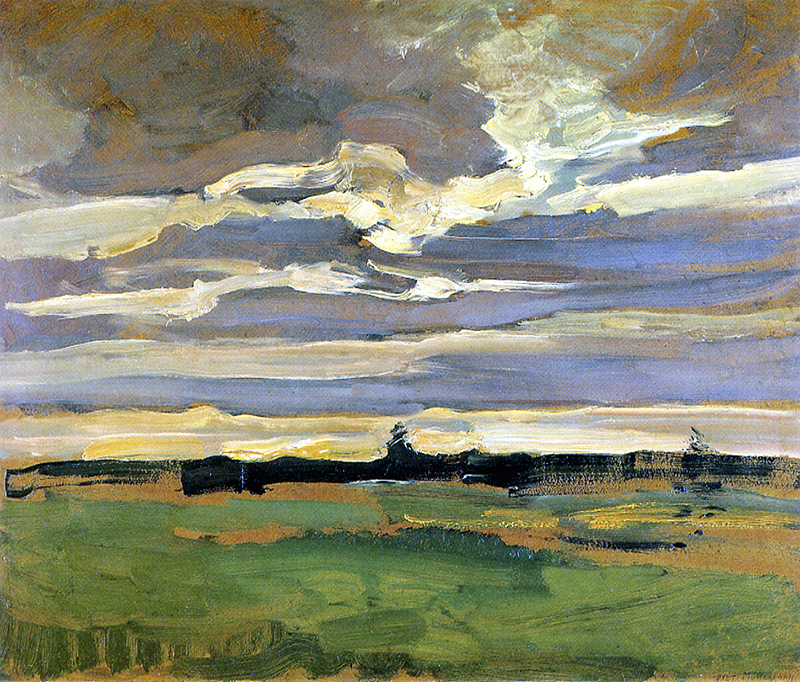

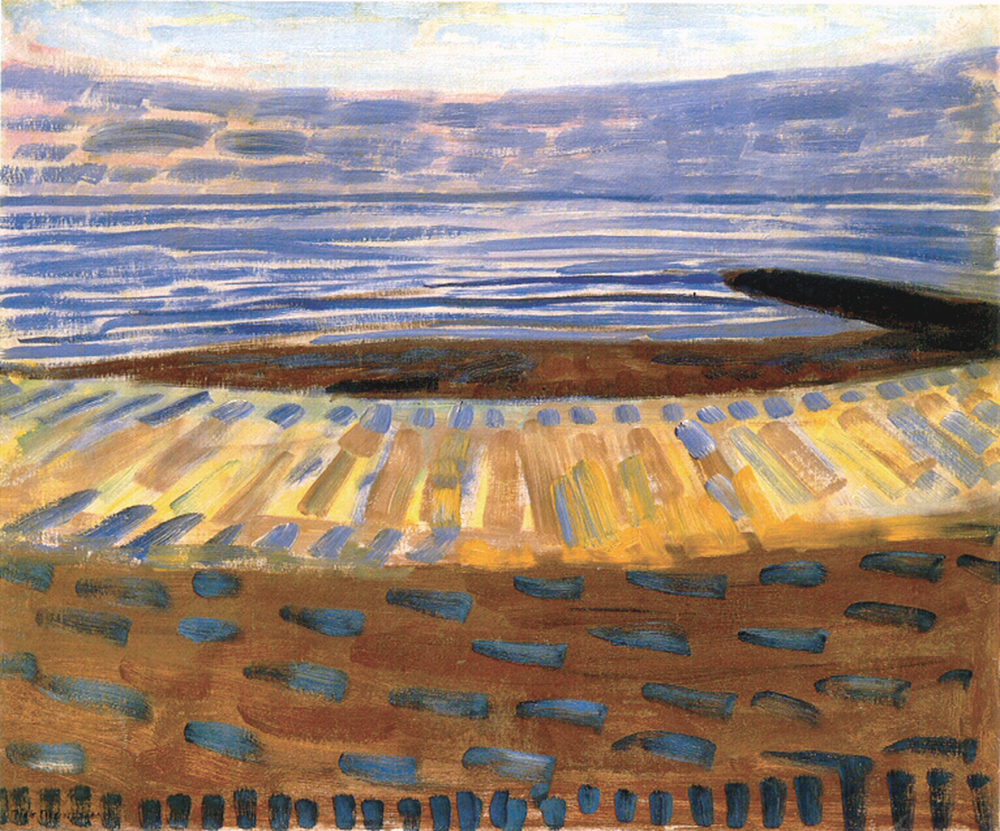

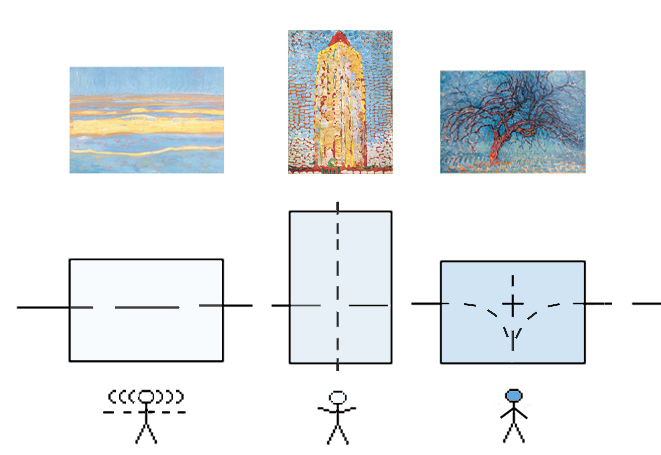

Examination of this period reveals in fact a gradual opening up of the landscapes, which now appear, with respect to the rural scenes of previous years, like boundless horizontal expanses. The landscapes are gradually stripped of trees, houses and any other sign of human presence and seem designed to emphasize the infinite extension of natural space:

As art historian Hans L. C. Jaffé observes, “His confrontation in 1909 with the infinity of nature coincides with his joining the Netherlands Theosophical Society, where man’s union with the infinitude of the universe was a central problem.”

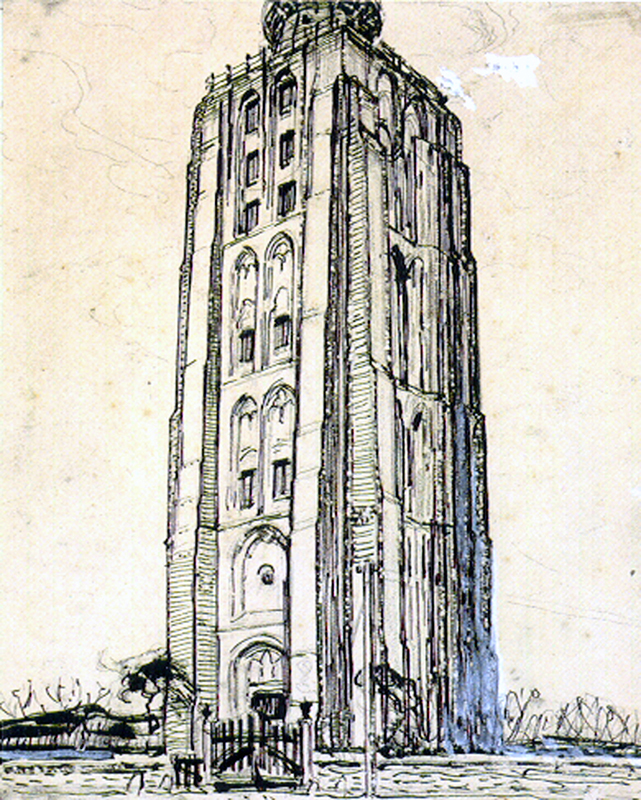

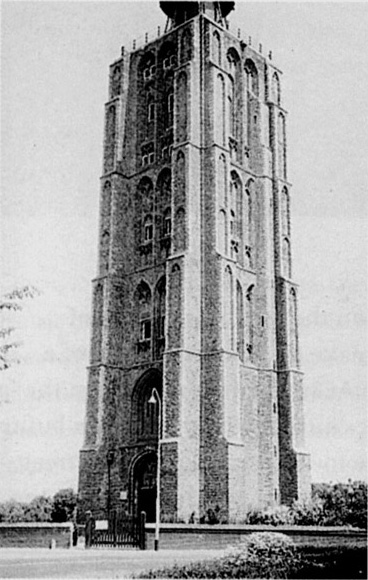

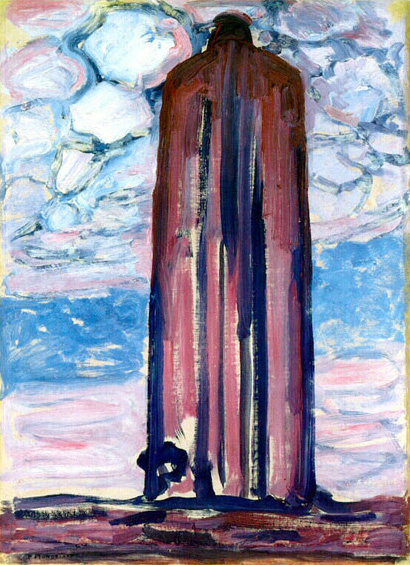

At the same time the painter’s attention turns to constructions such as mills, lighthouses, and church towers:

Let us now have a closer look at some of these horizontal landscapes and vertical architectural volumes:

Landscapes

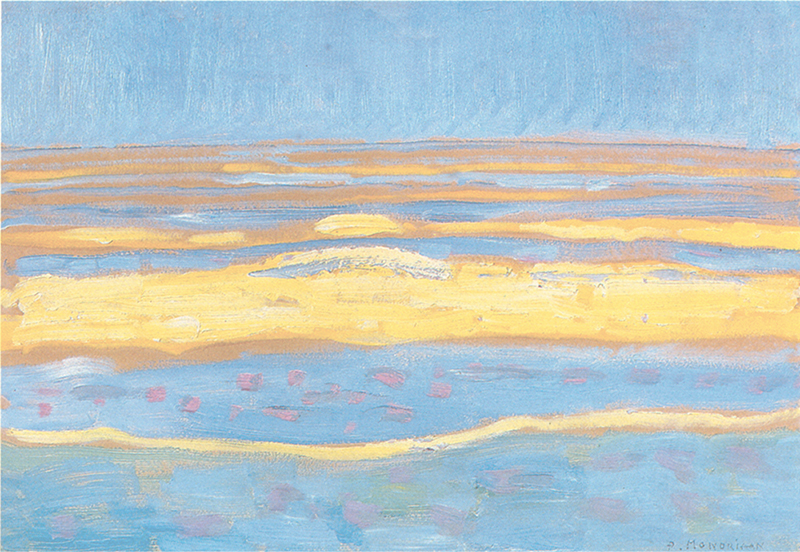

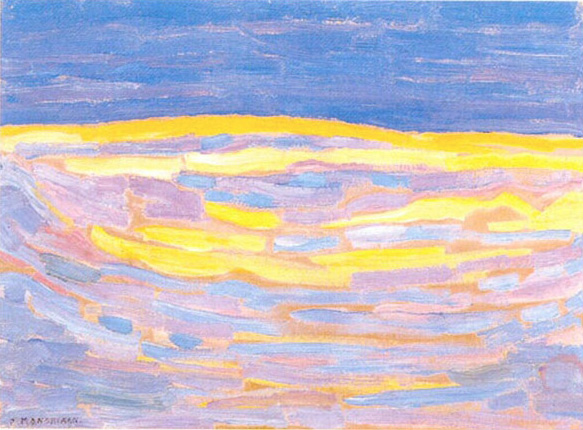

Seascape, 1909,

Oil on Cardboard, cm. 34,5 x 50,5

Fig. 1 is a small canvas with bright, contrasting colors. Blue, yellow, ocher, magenta, and a whole range of intermediate shades of these colors alternate between darker and lighter tonalities. Quick brushstrokes create a rhythm of elements grouped together by an uninterrupted horizontal flow. A yellow accent in the central area seems to detach and isolate itself for an instant from the continuous horizontal space.

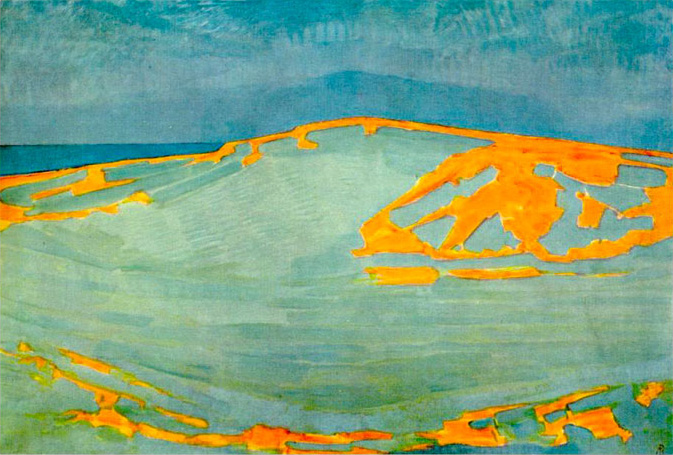

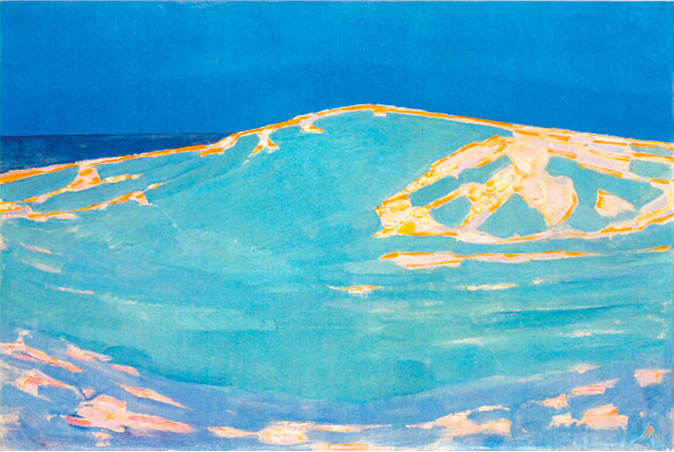

While some seascapes present a fully horizontal space (Fig. 1), other works inspired by dune landscapes along the coast, show a slightly raised profile of the horizon that coincides with a hypothetical vertical axis running through the center of the composition (Fig. 2 and 3):

Summer Dune in Zeeland, 1910,

Oil on Canvas, cm. 134 x 195

Dunes near Domburg, 1910,

Oil on Canvas, cm. 65,5 x 96

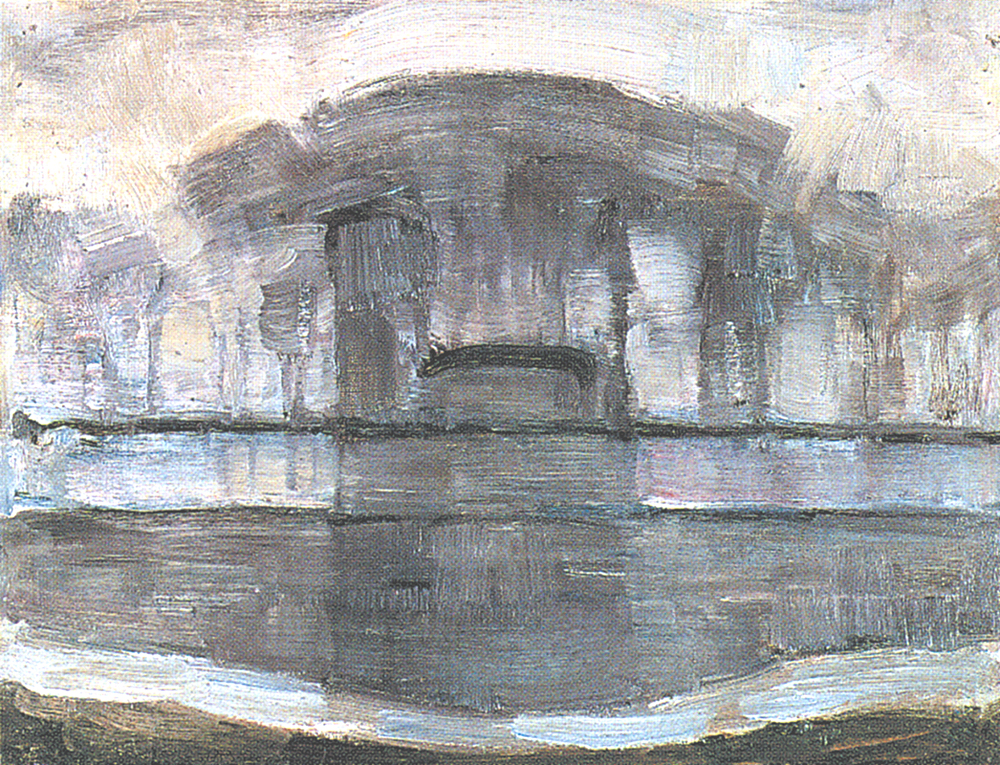

Similar to the central yellow accent we have seen in Fig. 1, Fig. 4 presents a dark accent standing out in the center of the composition.

While both Fig. 1 and 4 emphasize the continuity of natural space, those accents seem to mark a moment of pause in the incessant horizontal flow of the sea. As if the painter wanted to highlight the permanent situation of someone observing the dynamic becoming of the sea:

Sea Towards Sunset, 1909,

Oil on Cardboard, cm. 41 x 76

Geinrust Farm in the Mist, 1906-07,

Oil on Canvas, cm. 32,5 x 42,5

It looks as if the painter wishes to concentrate the infinite physical space of nature into the finite space of thought.

Something similar can be seen in Geinrust Farm with Mist of 1906-07 (Fig. 5) where a black segment representing the roof of a farm (a symbol of the steady human presence) is placed along a river (the flowing, ever-changing space of nature).

In Fig. 6, 7, 8 we see a curved line in the lower part that seems to draw all of the space into itself. Together with the horizon, which presents a slight upward curve in Fig. 7 and 8, the lower curved line suggests an oval shape:

Sea after Sunset, 1909,

Oil on Cardboard, cm. 62,5 x 74,5

Dune Sketch in Bright Stripes, 1909,

Oil on Cardboard, cm. 30 x 40

Pointillist Study of Dune, 1909,

Oil on Cardboard, cm. 29,5 x 39

The allusion to a possible oval shape seems designed to contain and endow with synthesis and greater permanence a space undergoing endless expansion.

The accents placed in the center of Fig. 1 and Fig. 4 , the line of the horizon rising in the middle in some canvases (Fig. 2 and Fig. 3) as well as the allusion to an oval shape are all signs of a search for unity.

I was struck by the vastness of nature and I tried to express expansion, tranquillity, unity”. (Mondrian)

It is worth recalling that during the naturalistic phase Mondrian had used an oval shape and an oval will be used again during the cubist period.

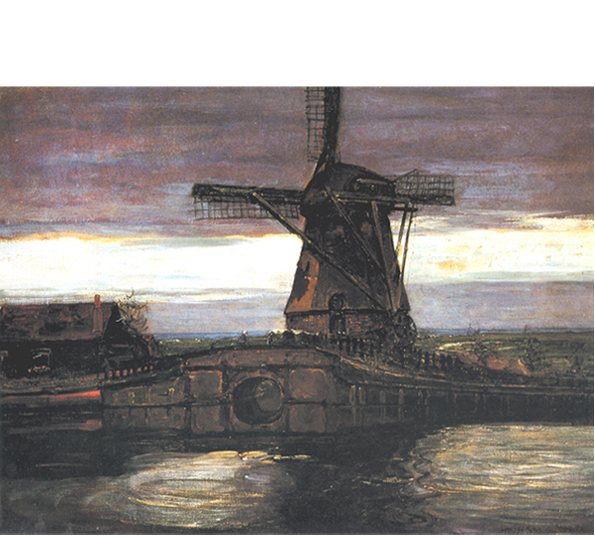

Architectural volumes

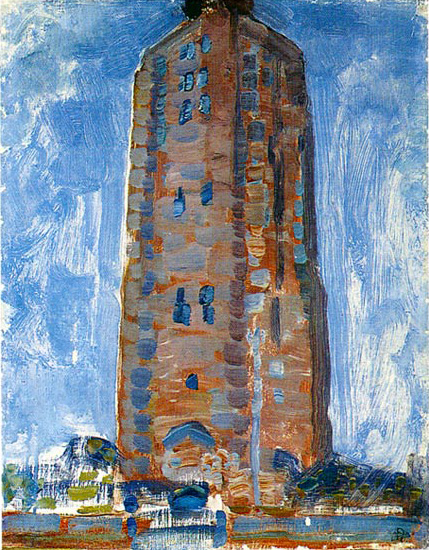

Similarly, but in the opposite sense to what we have just observed in the sea and dune landscapes, some paintings present exclusively vertical volumes (Fig. 1, 2, 3):

Lighthouse at Westkapelle, 1910,

Oil on Canvas, cm. 75 x 135

Lighthouse at Westkapelle, 1908-09,

Oil on Canvas, cm. 52 x 71

Lighthouse at Westkapelle in Brown,

1909, Oil on Canvas, cm. 35,5 x 45

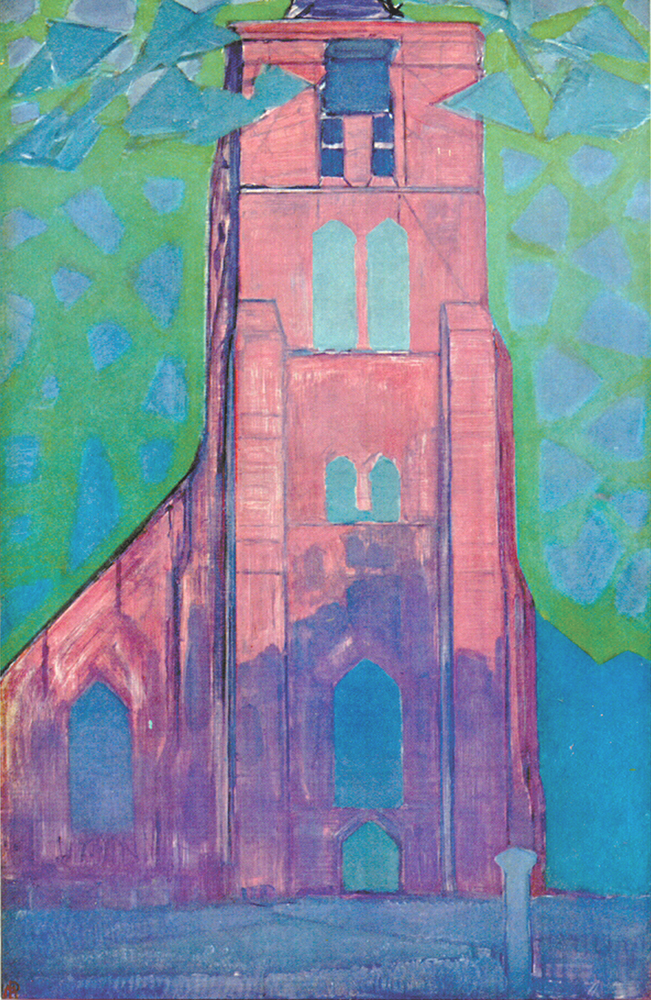

Some works present volumes in which a lateral offshoot appears to mediate between the vertical of the building and the horizontal of the ground (Fig. 4, 5, 6):

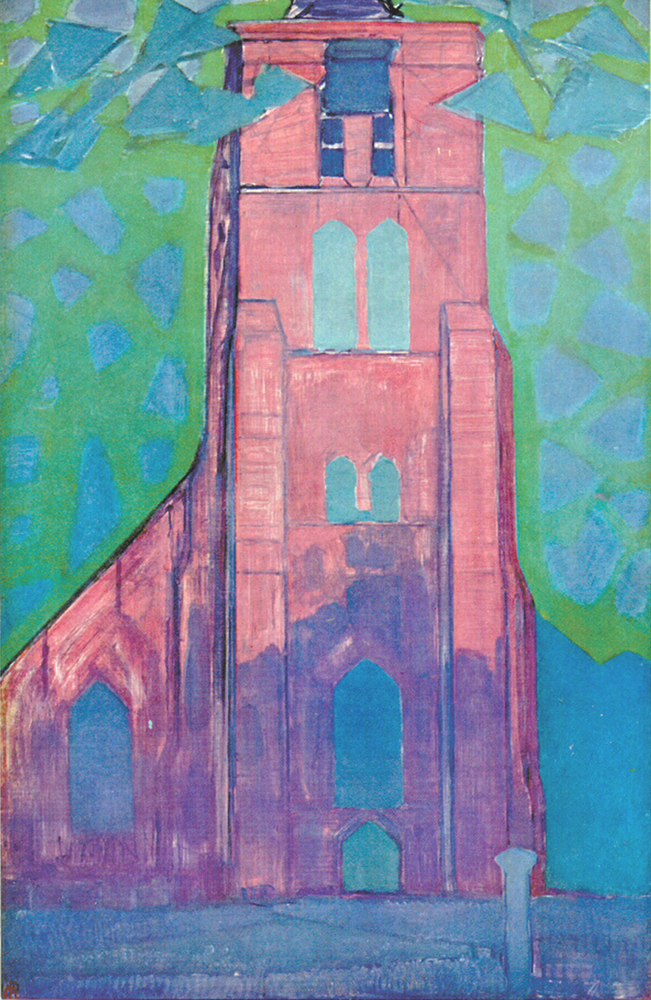

Church Tower at Domburg, 1911,

Oil on Canvas, cm. 75 x 114

Fig. 7 appears to display interpenetration between a dune-type landscape, i.e. nature (in the lower part) and a building, i.e. human artifice, (in the mid-upper part):

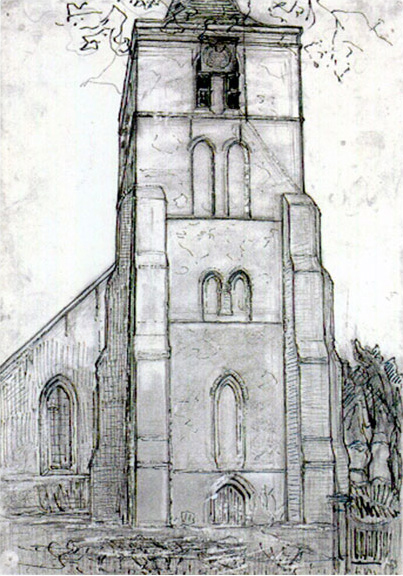

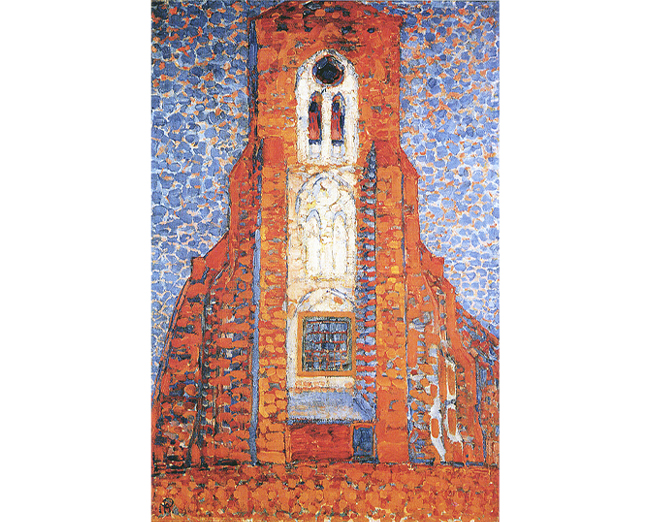

While some canvases display the use of fluid material applied in broad brushstrokes (Fig. 2), others present a surface divided into small dot-like marks (Fig. 8):

For this reason certain works have been described as “pointillist” or “divisionist”. It should be pointed out, however, that Mondrian’s “pointillism” has very little in common with the work of Seurat, Signac and Cross. While the latter used the dotted structure in order to translate variations in light and capture them on canvas, the Dutch painter, like Cézanne, adopted it in his search for a sort of common denominator underlying the variation of mutable things presented by reality around us; a common denominator between “empty” and “full” portions of space which are indeed different level of concentration of the same energy.

Summarizing so far: In the compositions that expand horizontally, the gaze opens up to the infinite dimension of nature, while the vertical compositions with the buildings bring everything back to the finite dimension in which the human being thinks, plans and builds to rise from a primitive condition of nature:

Nature and non-nature

As mentioned in a previous page, the history of mankind has been a slow and laborious process of emancipation from natural conditions ever since the Stone Age. In striving to improve their living conditions, human beings alter the landscape with architecture and transform nature into artifice (the countless objects and tools used for human life today).

How are we to define artifice? Is it a natural product or only a human product? And if mankind is part of nature, are the plastic, concrete, glass and aluminum used to alter the landscape and move faster between continents the result of natural evolution? It seems as if nature creates a “non-nature” through mankind. A curious contradiction. A contrast that finds a visual rendering with a vertical opposed to an horizontal.

Moreover, the inner life of human beings is marked by the search for equilibrium between contradictory drives such as the natural instincts and what we call intellect, reason or mind or as Mondrian used to say the Spiritual, and hence opposition between a part of us that is closer to the natural world and another that most distinguish and separate mankind from the rest of nature.

Nature and “non-nature”, the Natural and the Spiritual find concrete visual expression with the horizontal-vertical opposition. The painter appears to focus in this phase on expressing contrast, both with the alternation of opposing thrusts and through the use of strong colors. Yellow is opposed to pink or green; red is opposed to blue; horizontal compositions are juxtaposed with others characterized by marked vertical development.

The landscapes of the naturalistic period include numerous works showing rows of trees along rivers:

Oil on Canvas, cm. 31 x 38

Oil on Canvas, cm. 27 x 48

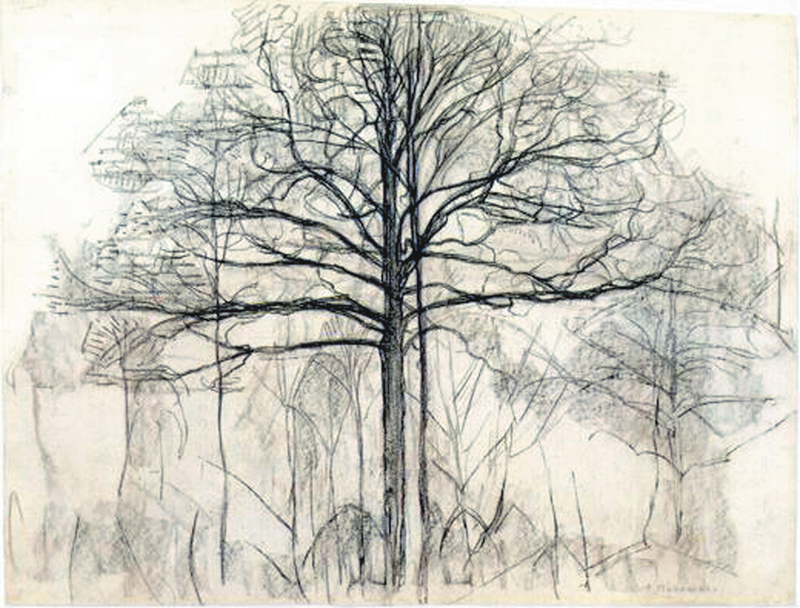

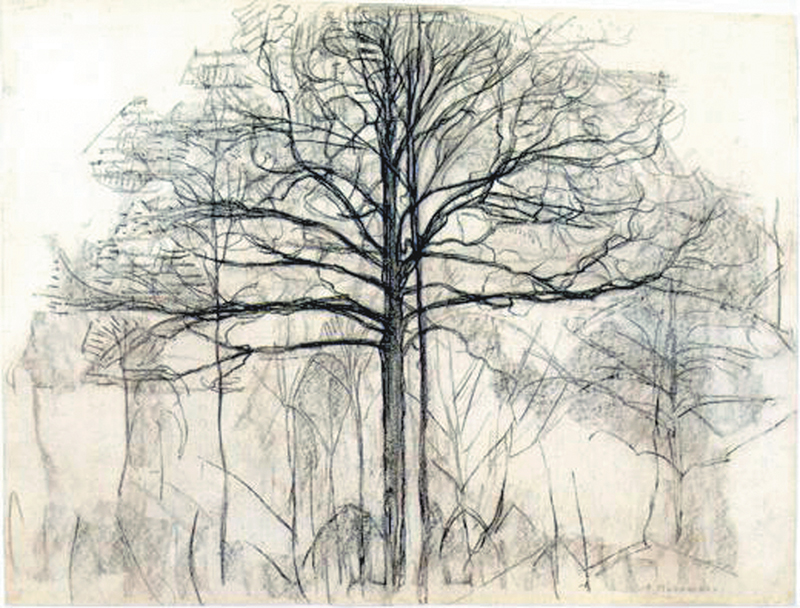

These gave way to paintings emphasizing the silhouette of a single tree:

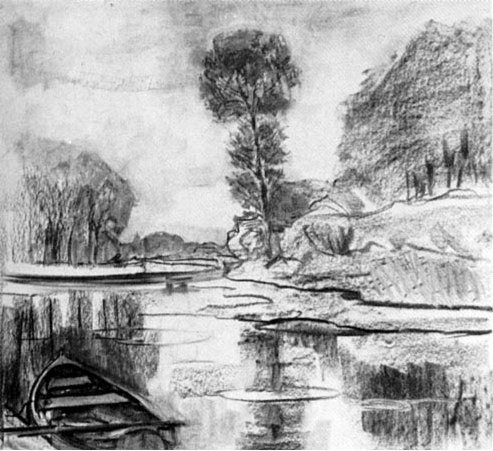

Charcoal and Stomping on Paper, cm. 58,8 x 65,5

Oil on Canvas, cm. 65 x 86

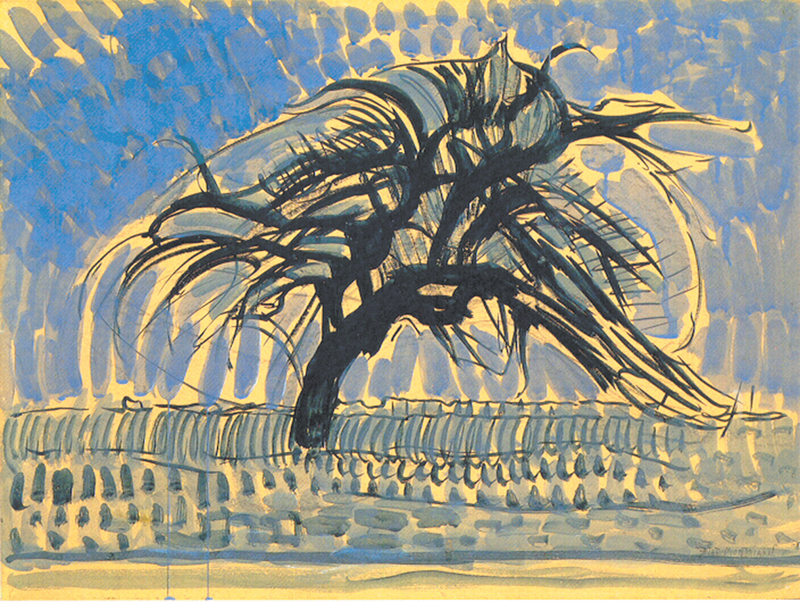

which became predominant in some works of the expressionist phase:

Charcoal and Stumping on Paper, cm. 32 x 49

Tempera on Cardboard, cm. 75,5 x 99,5

Oil on Canvas, cm. 70 x 99

Black Crayon on Paper, cm. 66 x 89,1

While Mondrian contrasts the absolute horizontal expressed through the landscapes with a sudden and massive vertical thrust of architectural volumes, the two opposing directions interpenetrate and relativize one another in the figure of a single, bare tree:

The branches expand toward the sides of the canvas while the trunk holds them back toward the center. In the figure of the tree space simultaneously expands (the branches, similar to the horizontal extension of the landscapes) and contracts (the vertical concentration of the trunk similar to the buildings).

Visual metaphors

Mondrian was a great painter capable of transforming the surface of the canvas into a precious artifact as regards richness of texture, combinations of color, and dynamic balancing of the composition. It is essential to see the original works in order to appreciate all their beauty. His aim in painting those landscapes, mills, lighthouses and trees was not, however, solely to reproduce the fleeting appearance of things. The artist read and interpreted those objects as plastic symbols of a deeper reality, as visual metaphors of existential meanings. Mondrian’s eye addressed the objects and situations of the external world but pulsated with a wholly internal rhythm.

Mankind and nature

In the tree layout the artist imagines an ideal balance between the horizontal infinite expansion of the natural landscape and the concentrated, measured space of man-made vertical constructions. The fact that the artist finds in a tree the synthesis between nature and human artifice suggests that he has wished for an artifice (the vertical architectures) in balance and harmony with nature (symbolized by the horizontal). Think of today’s ecological question.

The tree becomes a visual metaphor of a search for equilibrium between opposites: The multifarious aspect of outer and inner nature as well as the unpredictable course of life (symbolically evoked by the crowded, irregular space of the branches) on the one hand and the human spiritual quest for constancy and unity (symbolically evoked by the solid, permanent trunk) on the other:

outer and inner space

In the tree, the horizontal of the natural land or seascape is concentrated in the trunk, which is equivalent to the vertical of the buildings. The trunk appears as an ideal projection on the canvas of the viewer in the act of mentally appropriating the natural space beheld.

The tree appears as a miniature universe that succeeds through its trunk in isolating itself from the unbroken continuity of the line of the ground (the infinite space evoked by the seascapes and dune landscapes).

It can therefore be contemplated as a manifold space (the branches) that expresses a manifold space (like the real world) while maintaining its unitary nature at the same time (the trunk); unlike the dunes, whose uninterrupted continuity disintegrates our field of vision.

In other words, the trunk would symbolize the unifying consciousness of man addressing the unforeseeable, infinite variety of the world suggested by the irregular, manifold space of the branches.

In this phase Mondrian was in search of space based on a relationship between opposing entities generating multiplicity and evoking unity at the same time. Contemplating the duality within oneself and the multiplicity around us; opening up the self to the diversity that life brings with itself but without forgetting that all that variety is a unity. Multiplicity and unity, infinite and finite, universal and individual: painting was becoming a form of spiritual exercise for Mondrian.

Multiplicity and unity

A relationship between multiplicity and unity can be traced back in some early naturalistic works such as Wood of Beech Trees that we have examined in the previous page:

Around 1899 Mondrian paints some trunks of beech trees in a wood. Each trunk has its own particular appearance and, all together, they express the sense of variety seen in nature. The landscape consists of vertical trunks which multiply and expand in a horizontal way. Toward the sides of the painting the horizontal line of the ground sharply contrasts with the vertical shapes of the trunks whereas in the central upper part of the composition horizontal and vertical merge together to become one.

It is as though the painter wanted to concentrate within a vertical (symbol of the spiritual) the variety seen in nature which multiplies here through a variety of different trunks in the horizontally way towards the sides; horizontal expansion that he would express years later with the horizontal landscapes and seascapes:

whereas the vertical trunks of Wood of Beech Trees will become the vertical volumes of the lighthouses and mills

and the figure of a tree where the two opposing directions compenetrate to express unity (the trunk) and multiplicity (the branches).

In The Red Tree we can see an analogous structure to Wood with Beech Trees but in a reversed mode, that is to say, with unity generating from the bottom toward the top instead of from the top to the bottom:

Expressionism?

I have referred to these works as expressionistic. As mentioned, this is not the type of Expressionism that was to develop around 1910, above all in Germany, inspired by a critical stance toward the society of the time and, in a more general sense, by chronic malaise with respect to the life typical of a certain north European culture. These canvases by Mondrian have never given me the impression of clumsy, overwrought space to be seen in many works of German Expressionism.

Even the bright greens, reds, magentas, and yellows of these paintings are always somehow classical and measured. Mondrian seeks to express space in a state of tension; he addresses oppositions and strong contrasts, which he then endeavors to resolve in a balanced whole that ultimately expresses harmony.The colors express tangible matter that is not, however, the matter of Van Gogh or Munch. Everything vibrates but the sound emitted is a deep and graceful note rather than a high-pitched shriek.The expressionistic phase was for Mondrian an initial step toward the process of abstraction that was to guide him throughout his existence.

Van Gogh, Cézanne, Mondrian

Van Gogh, the Fauves, and then the Expressionists used the accentuation of color to highlight the relationship between the outer world and inner space, between the object and the subject, in other words, the interpretation of reality. Mondrian found himself in harmony with this approach from his naturalistic phase on.

Unlike the Expressionists, however, he addressed the issue in greater depth and breadth between 1907 and 1910, considering the relationship between subject and object no longer solely through the chromatic transposition of sensory data (as Van Gogh had done and as the Fauves and Expressionists were doing at that time) but also through the search for a more solid formal structure (as suggested by Cézanne’s work) with the progressive orientation of his compositions toward dynamic interaction between horizontal and vertical (seen respectively as plastic symbols of the external and internal worlds). With the dunes, the buildings, and the tree, Mondrian was unknowingly channeling the work of Van Gogh and Cézanne into a single approach.

Mondrian opened up the canvas to the infinite space of nature with the dunes and concentrated it all before him for an instant with the buildings. The two opposite motions reached interpenetration in the tree. This marked the dawn, the very beginning of a dialogue between the two opposing directions that was to occupy the artist for his entire life, a dialogue that essentially meant the search for greater equilibrium between inner and outer worlds, the human subject and the natural universe.

It is a great pity that the reading of these explanations cannot be accompanied by enjoyment of the brilliant greens, the thrilling oranges, and the deep and graceful shades of blue used to tone down the vivid yellows and bright reds of these wonderful canvases. One of the most interesting aspects, to which we shall be returning at length, is the fact that Mondrian’s sensitivity to philosophical and spiritual themes does not transcend but indeed takes concrete shape in the beauty of the world, its colors, and its forms.

next page: Mondrian’s Symbolism

back to overview

Copyright 1989 – 2025 Michael (Michele) Sciam All Rights Reserved More