How does Mondrian come to a space based on a relationship between horizontal and vertical straight lines?

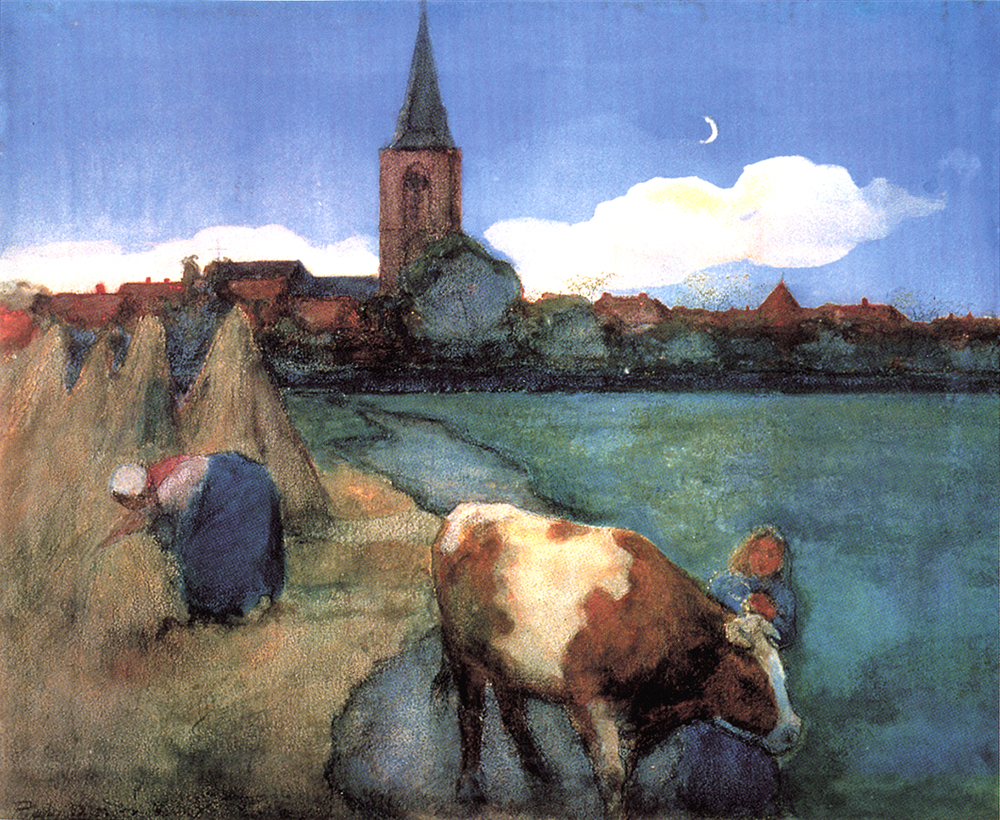

The artist begins to paint in accordance with the tested canons of the naturalistic painting, otherwise called figurative:

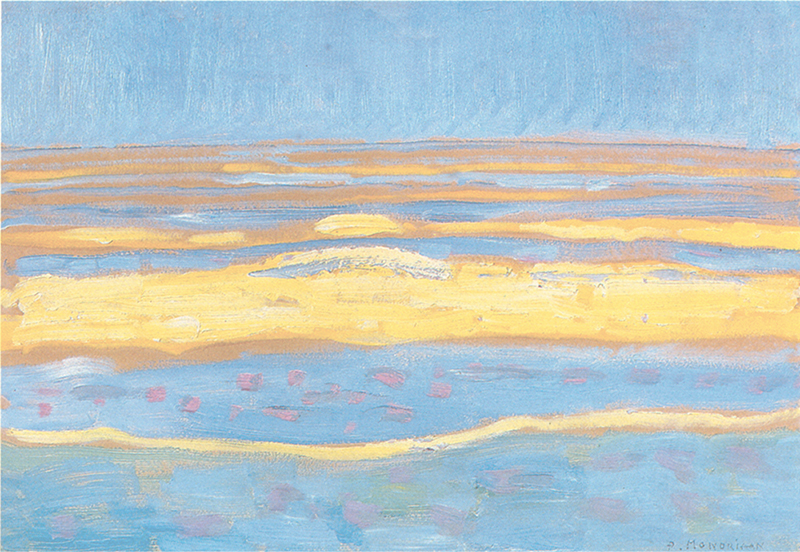

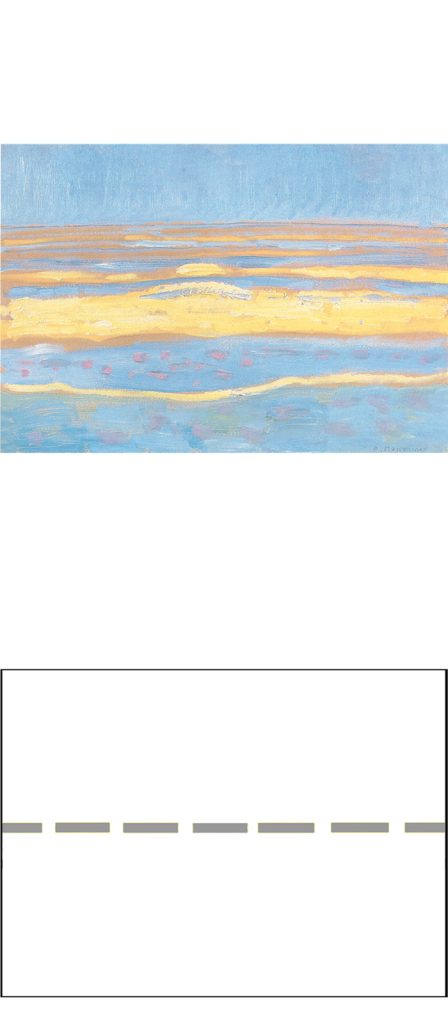

Around 1907, the earlier landscapes of the naturalist phase are stripped of trees, houses, and any sign of human presence and seem designed to evoke the infinite extension of an unspoiled nature:

As art historian H. L. C. Jaffé observes, “His confrontation in 1909 with the infinity of nature coincides with his joining the Netherlands Theosophical Society, where man’s union with the infinitude of the universe was a central problem.”

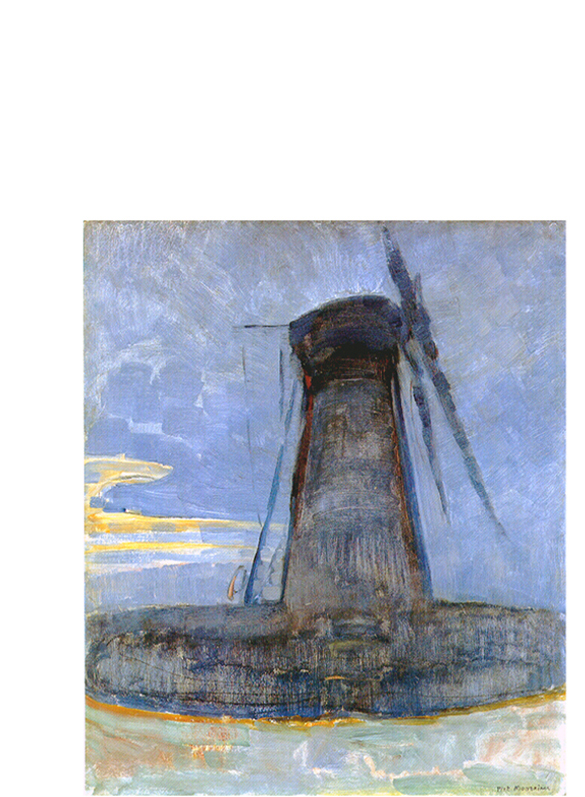

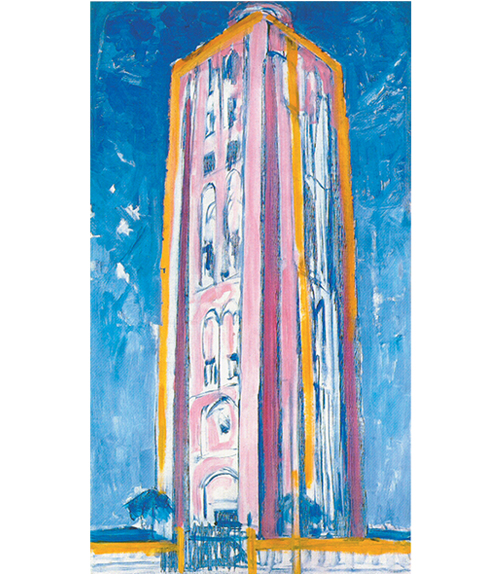

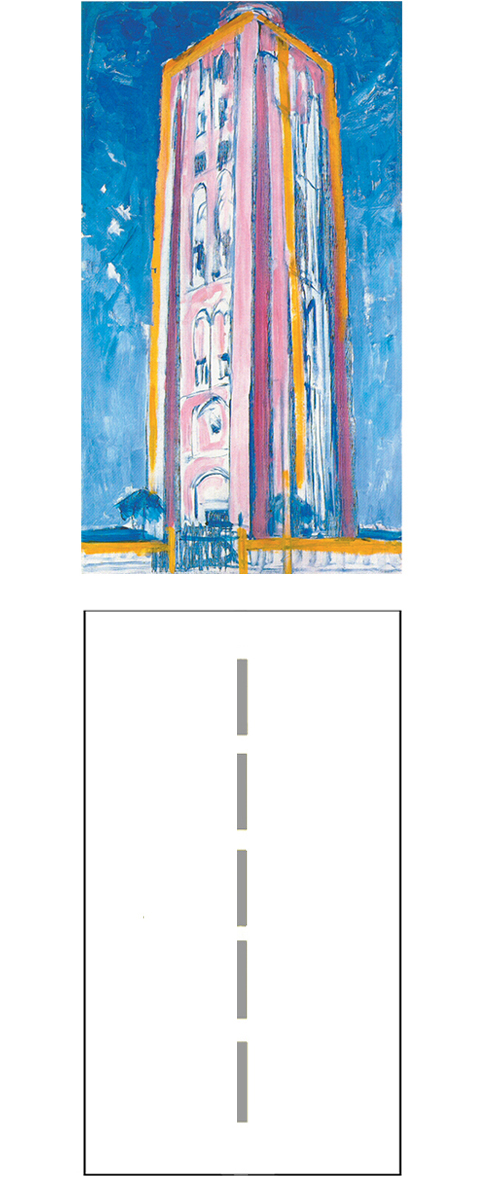

At the same time the painter’s attention turns to constructions such as mills or lighthouses:

In the compositions that expand horizontally, the gaze is opened to the infinite dimension of nature while in the vertical architectures everything is concentrated into a finite space in which human beings think, design and build to rise from a primitive condition of nature.

Mondrian wrote that the horizontal represents the Natural while the vertical evokes the Spiritual.

The vertical elevation expresses mankind’s atavistic propensity to imagine a spiritual dimension extending toward the ethereal space of the heavens rather than remaining bound to the everyday matter spread out horizontally before our eyes.

The Natural and the Spiritual

The artist ascribed to the horizontal the value of everything that can be defined as “natural” not only in the sense of the natural extension of the land but also as anything that during our life around and within us unpredictably changes.

In the vertical the artist instead saw a symbol of the “spiritual” that is, of the all-human propensity to transform infinity into finite and seek stability, constancy, unity.

Our lives unfold through a dynamic interaction between instincts and reason, mutable and constant, multiplicity and unity, that is to say, between opposite drives. How to express opposite drives in the bi-dimensional space of painting? A way is to generate a dynamic contrast between horizontals and verticals.

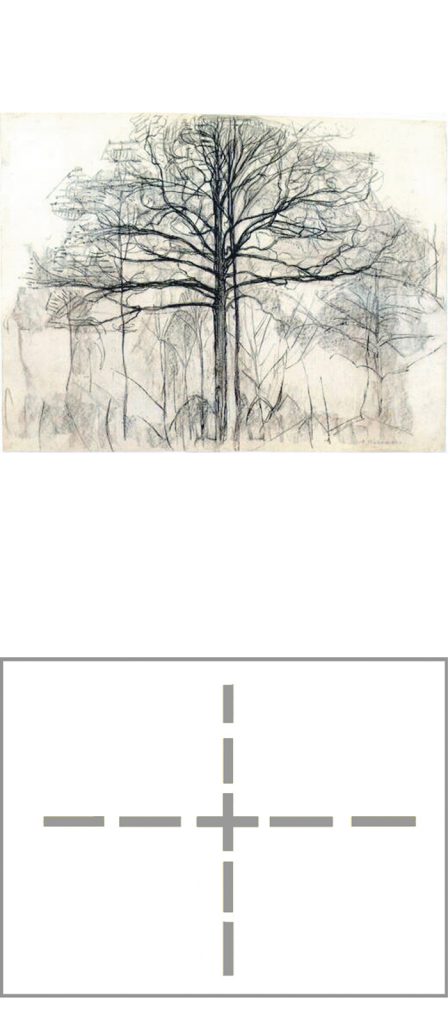

While an horizontal compositional space prevails in the landscapes and a vertical layout in the architectures, the opposite directions merge together as the basic structure of a bare tree:

In the figure of the tree Mondrian evokes a balanced synthesis of the opposite directions (the horizontal expansion of the branches and the vertical concentration of the trunk), that is, of what the artist considers as symbols of the Natural and the Spiritual.

The abstract compositions of the following years formed by horizontal and vertical lines are already present in the figure of a tree although still in a form veiled by appearances.

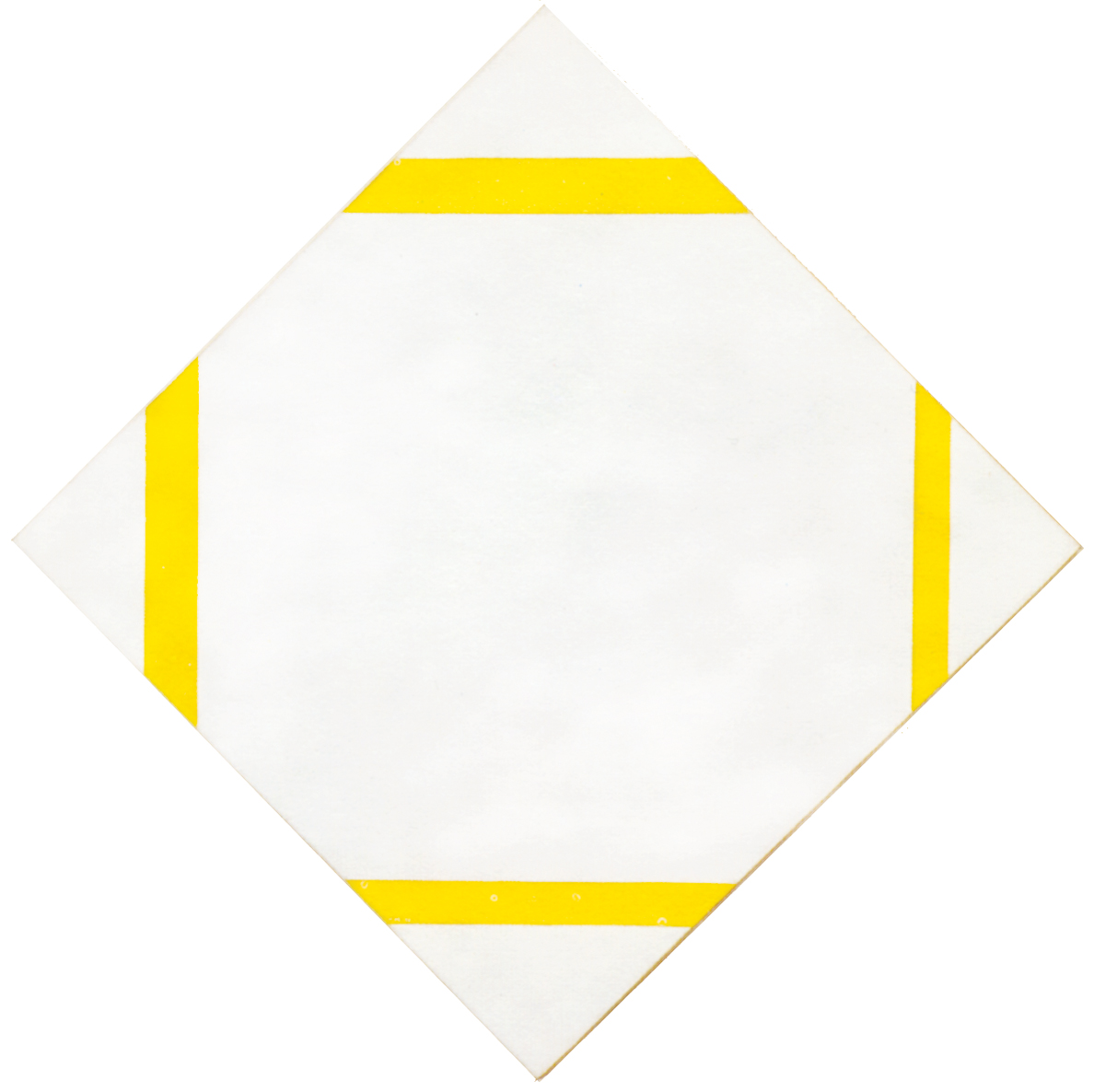

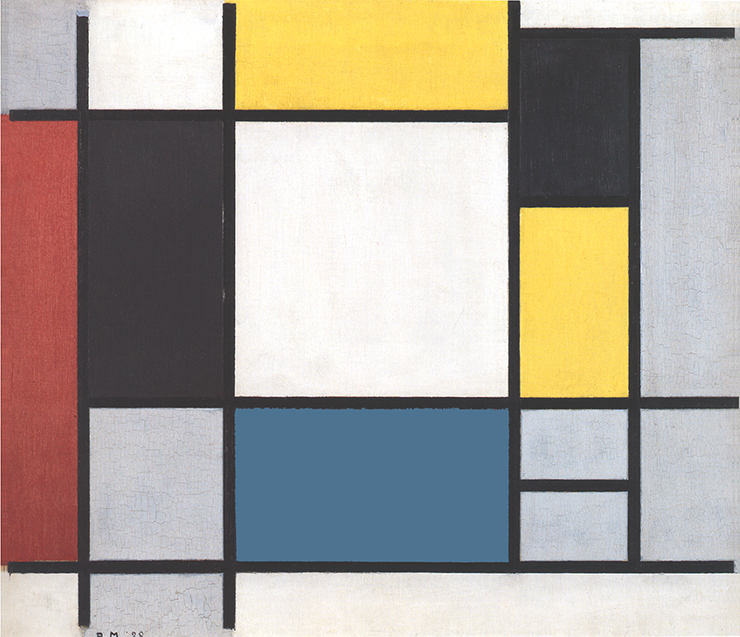

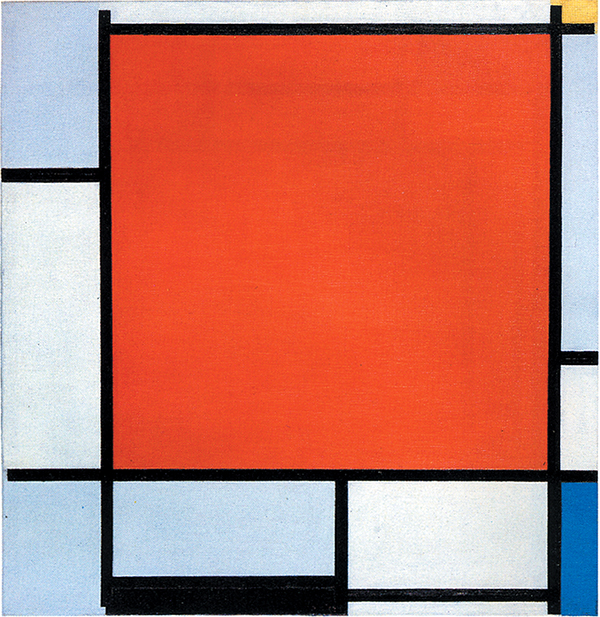

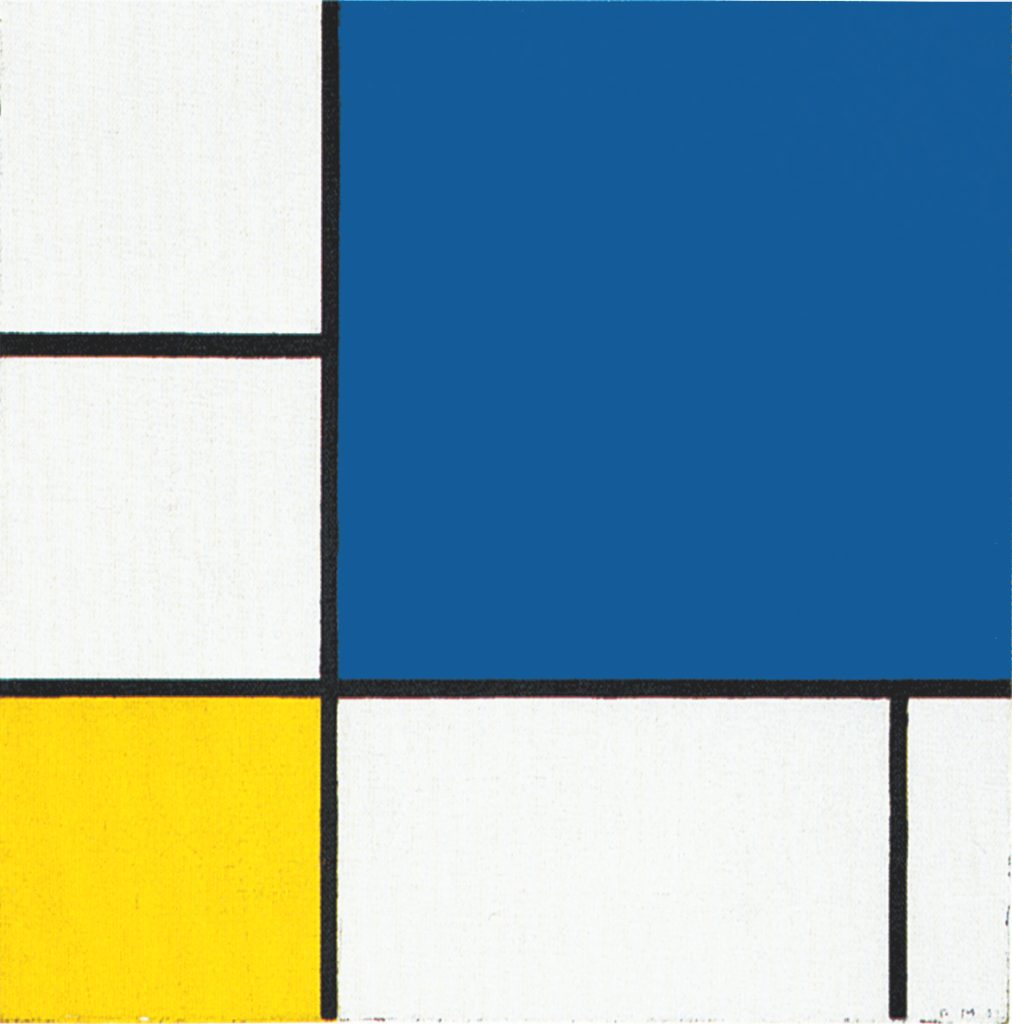

In the abstract works we shall see an on-going dialogue between opposite lines which, on the one hand, generate rectangles of varying size, proportions and colors (Fig. 10, 11) i.e. a mutable setting (symbol of the Natural) while, at the same time, give birth to square proportions. (Fig. 10, 11, 12). A square comes into being when horizontal and vertical acquire the same value, that is, when the duality expressed by opposite lines, which elsewhere generates multiplicity (the Natural), transforms into unity (the Spiritual).

A dynamic interaction between multiplicity and unity will be one of the fundamental guiding threads of Mondrian’s entire oeuvre.

Copyright 1989 – 2025 Michael (Michele) Sciam All Rights Reserved More