Eighty years after the death of Piet Mondrian, we still find ourselves halfway between a plastic space that is old but still real for many, namely naturalistic or figurative painting, and a newer and more functional type of space used by a growing number of people that is not yet capable of constituting a tried and tested language, a canon serving as a yardstick to establish what the art of painting consists in today. Has the time perhaps come to sketch out a code for the new form of painting? What can we take as the grammar and syntax of the new plastic space?

I am obviously not referring solely to painting as traditionally understood but also to the whole range of expressive possibilities offered by the new techniques of visual representation. Even though I believe that the new space depends to a great extent on the work of Piet Mondrian, a code for the new painting will not be based solely on Neoplasticism as handed on to us by the Dutch artist. I am also thinking of Matisse’s last period and his masterly use of color, Mark Rothko’s vibrant textures, the “repetitions” or variations introduced by Andy Warhol, and the spontaneous, uninterrupted continuity of space evoked by Jackson Pollock.

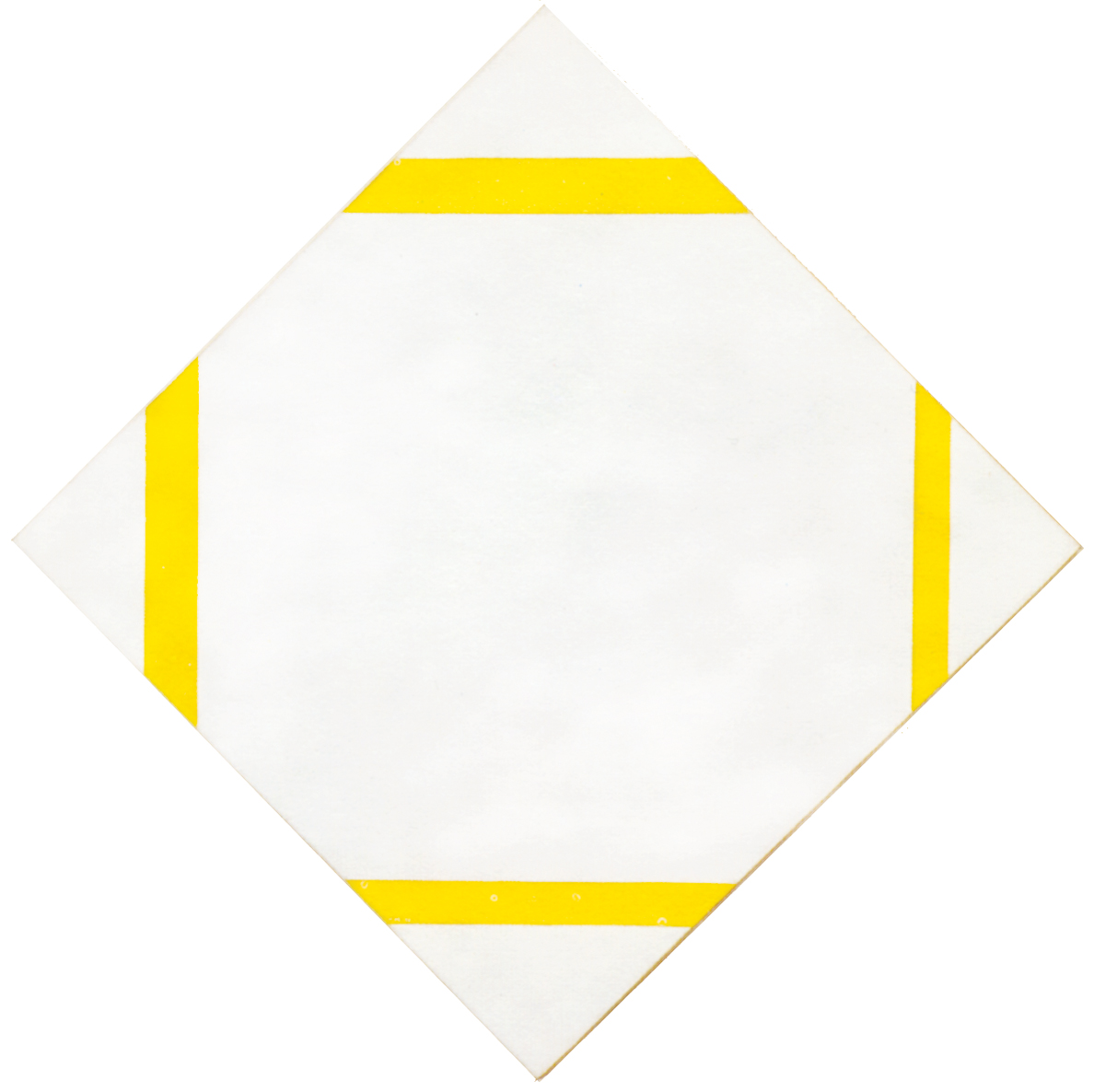

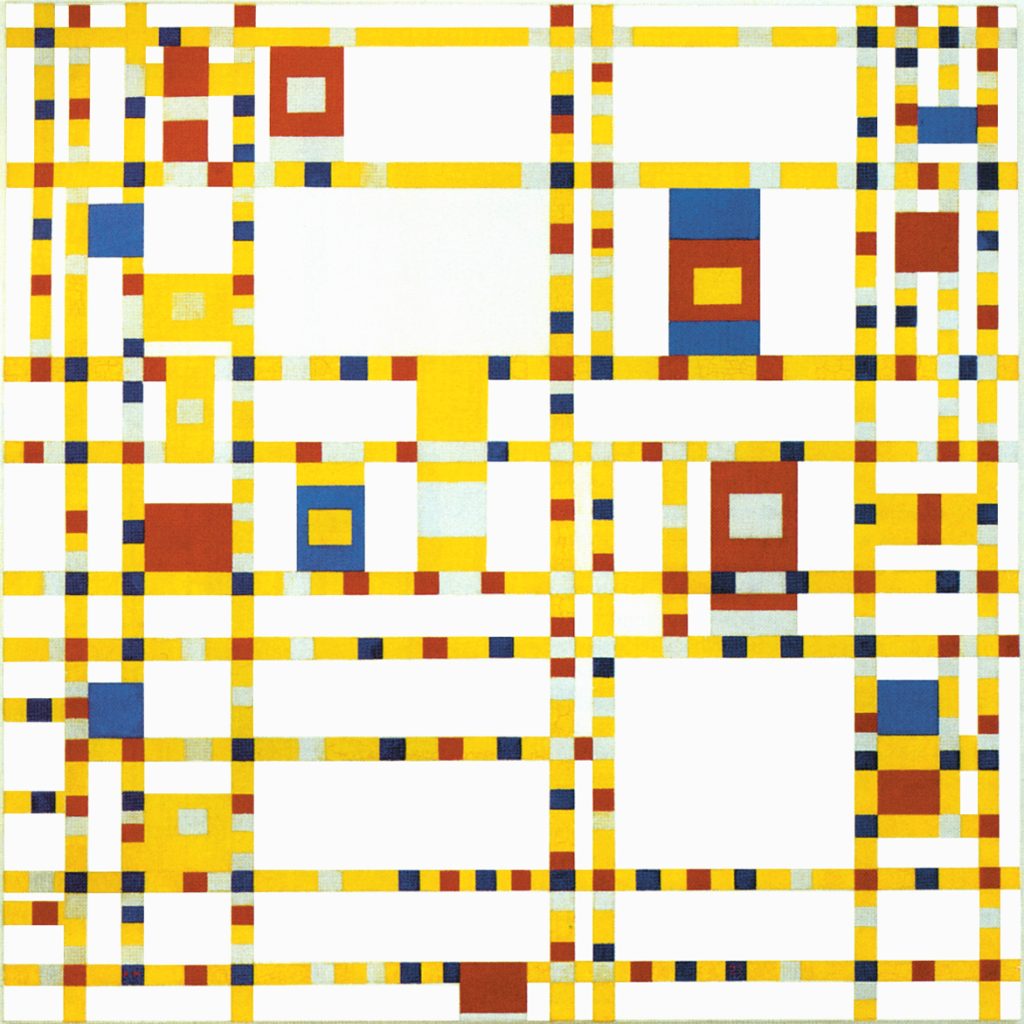

As a matter of fact, I do not believe it necessary to paint like Mondrian in order to produce true abstract art. To give just one example, let us compare Broadway Boogie Woogie with two apparently very different works which, however, show affinities with Mondrian’s work:

Zen

We shall start with the painting of an unknown Zen painter of the 18th century:

At first sight this work appears to be the very antithesis of a Neoplastic work. It is a painting of a circle that opens up again just when it is about to close, a circular process where the end coincides with a new beginning.

Unlike the geometry constructed by Mondrian, that of the Japanese artist requires a rapid gesture of the hand. But how much practice was needed before such a well-formed circle could be painted in one go. It is an open and imprecise circle that evokes natural energy and at the same time manifests the striving for perfection typical of human thought; a circle that expresses our idea of a universal cycle of life with the spontaneity that life alone possesses.

Between everyday and eternal

The circle seems to contain all the impermanence of the moment within itself while nevertheless striving for almost absolute fulfillment, a circle in a state of becoming; in unstable balance between indefinite and definite, particular and universal, everyday and eternal. Like Broadway Boogie Woogie, this image is capable of evoking a dynamic unity of all things. That gesture, as fast as lightning, seems to enclose the secret of life itself.

Broadway Boogie Woogie shows a process from a variety of yellow, red and blue fragments concentrating into a unitary plane of these colors and then a re-opening of the unitary plane towards new multiplicity.

A composition where an end of the process (a multiplicity concentrating into a unity) coincides with a new beginning (a unity opening up to multiplicity) evokes a circular process.

A circular process

While a circular process evoking the cycles of nature is generated in both images, in one case (the circle of the Japanese artist) it is a matter of immediate intuition that captures unity without too much concern for its manifold aspect. Broadway Boogie Woogie instead presents a mediated vision that proceeds through a large variety of particular forms, differing from one another, before showing how they all intrinsically belong to one and the same process.

Sacred visions of life

The spontaneous gesture of the Japanese painter is broken down in Mondrian’s composition and arranged in a complex pattern of forms that are developed, juxtaposed, and finally brought together. We could say that the western painter seeks to break the spontaneous gesture down into a succession of considered moments. Both are sacred visions of life, but the Japanese work tends toward a mystical and absolute mode of expression while Broadway Boogie Woogie endeavors to organize itself, to explain itself, and to assume the relative nature always possessed by our fragmented experience of reality.

Discipline

I wish to make it clear that the spontaneity I am talking about corresponds to the most advanced stage of a long and patient exercise of discipline that must be completed before you can let go without missing the “target”.

This is what Matisse writes about spontaneity: “Novice painters think they are painting from the heart. Artists at the peak of their development also think they are painting from their heart, but they alone are right, because the training and discipline they have imposed upon themselves enable them to accept its impulses.”

Henri Matisse

Another example of true abstract painting (even though the title could prove misleading here too) is a work that Matisse produced in 1953.

I refer to a cutout or papier découpé: Hand-made Montgolfier brand paper colored by the artist’s assistant, cut out in accordance with compositional requirements and glued onto canvas.

Every plane has a certain color and assumes its particular shape in relation to the configuration and color of the neighboring planes. As a whole, the planes evoke a circular motion that can also recall the spiral shape of a snail’s shell, whence the title L’escargot. As pointed out with respect to Broadway Boogie Woogie, this work too should have been given a more neutral title so as to avoid prompting the inexpert observer to see nothing but a snail in this splendid and far more significative composition.

A unitary process

Once again it is an image that seeks to evoke a dynamic unity made up of the most disparate entities. While every plane differs from the others both in shape and in color, they all form part of a unitary process. As in Broadway Boogie Woogie and the work of the Japanese painter, we again see a circular structure that generates an impression of variety and evokes synthesis and unity at the same time.

Between Zen and Mondrian

The extreme synthesis generated in the Zen painting is arranged here in a series of parts. The immediate and very visible circle of the eastern painter becomes a circular motion that takes shape in a more gradual and structured way. Matisse’s work can be described as being midway between the almost absolute circle of the Japanese painter and the circular process generated by means of straight lines by Piet Mondrian. It expresses a degree of multiplicity that is greater than the Zen painting but not so great as the Neoplastic composition.

I will not even try to describe the beauty and the healthy energy that emanates from this masterpiece by the French artist. It is well worth a trip to London and a visit to the Tate Gallery to observe the work at first hand. (I am not sure if it is still named Tate Gallery or Tate Modern..)

Broadway Boogie Woogie, a painting by an anonymous Japanese artist, and Matisse’s L’escargot: three images that speak to us in their very different ways about the same. Abstraction does not mean adopting a certain style but rather the capacity to capture the essence of things, each in his or her own way.

Abstract art

It is not necessary to paint like Mondrian. It is possible to talk about the same things in different ways; but filling a canvas up with just any shapes and colors is not enough to produce a work of abstract art, just as any combination of words or notes is not enough to create a work of literature or music.

The beauty and the rightness of certain combinations of color and forms are things that cannot be taught or learned and still less explained in words. They are either there or not there. You either know how to recognize them or you do not. Color has its own inherent expressive strength that a good painter must know how to calibrate, like the notes of a musical composition.

A primitive stage

Just as the same words can be used in verbal language to come out with nonsense or to construct splendid phrases rich in meaning, so it is with the language of forms and colors. The vocabulary is common to everyone but the difference between an image of fully expressed significance and one devoid of sense mainly depends on the use made of that vocabulary. In the absence of established rules and canons for the new form of painting, we are today at a primitive stage where everyone thinks themselves capable of creating an abstract work of art. We seem to be surrounded by a great mass of illiterates who want to make us believe that they can write poems.

All possible waves

Through the deft use of shapes and colors, abstract art can evoke the intimate nature concealed behind the changing appearances of life, contemplating it as one might contemplate the immensity of a sea with all its waves, every new wave appearing to be different from all the others but always consisting of water. There is a form of painting that looks to the particular appearance of a few waves and one that is capable of concentrating on the state of becoming of the water and hence of seeing all the possible waves.

This presupposes an uncommon sensitivity that succeeds in looking beyond manifold appearance, but also something more, namely the ability to give concrete form to one’s inner visions, which requires a great amount of talent if the images are to gladden the eye and be transformed into content that enriches the mind and the spirit; all of which is unfortunately quite rare on the contemporary official artistic scene.

Empty syntheses

We are today presented with a great amount of self-styled abstract art that actually has more in common with wallpaper. Even among those prompted by honest intentions, there are very few works of abstract art born out of a fertile observation and distillation of reality. Most of the time, contemporary abstract painting presents syntheses that prove empty.

This is what Matisse said to Verdet about a canvas by Cézanne: “It takes a great deal of analysis, invention, and love to arrive at the simplicity of the bathers you see at the end of the garden. You have to be worthy of them, to deserve them. As I have already said, when the synthesis is immediate, it is schematic, lacking in density and impoverished in expression.”

Mass consumption

Variations of form become content in Broadway Boogie Woogie, but it is not just any variation of form that can evoke content. There are unfortunately not many people capable of seeing and distinguishing compositions in which form becomes content from ones where content never come to life. And those few no longer count in a society where mass consumption predominates, hence the confusion prevailing in the contemporary artistic panorama.

As always, confusion means a great opportunity for fraud. This is why most of what is put forward as “contemporary art” today does not really possess the qualities one would expect to find in a genuine work of art.

Copyright 1989 – 2025 Michael (Michele) Sciam All Rights Reserved More