Reflections on other aspects dealt with by Raffaello and Mondrian

Symmetry and asymmetry

In the two ancient frescoes a variety of human figures generates areas of asymmetrical space within a composition that tends to an overall symmetry:

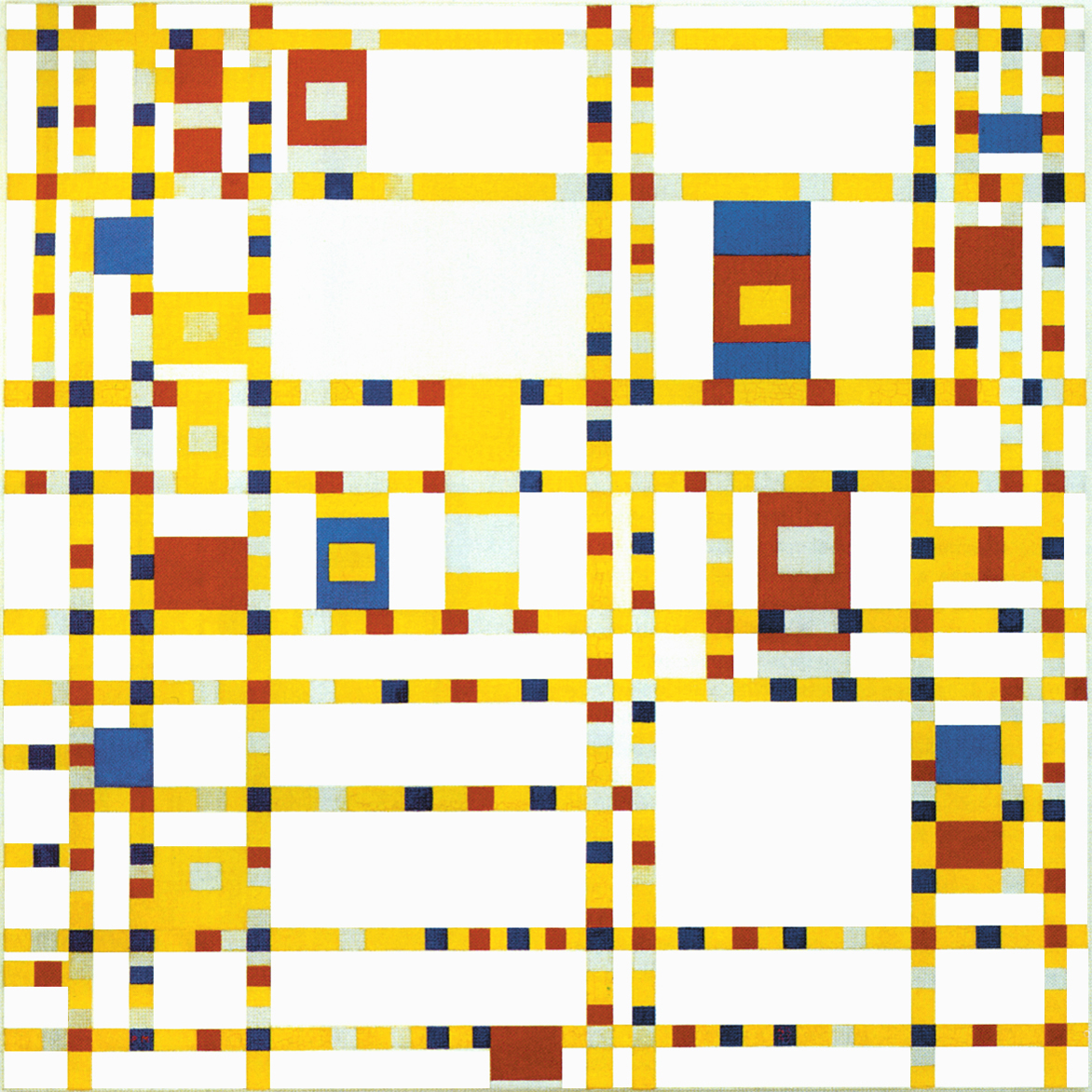

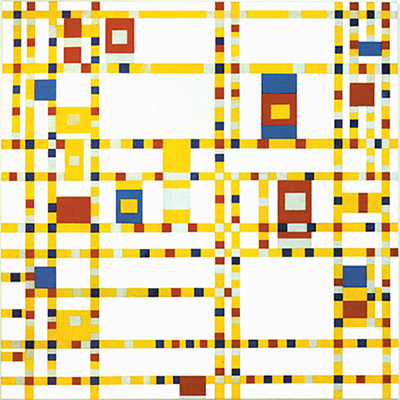

In the modern painting we observe, on the contrary, short sequences of symmetrical space within an entirely asymmetrical composition:

The symmetries generated in Broadway Boogie Woogie are momentary tendencies towards a certain order that never come to govern the entire composition as in La Disputa del Sacramento and La Scuola di Atene.

Ordering disorder

A symmetrical linear structure evokes a central point around which the elements remain identical. The concept of symmetry tends to transform the unpredictable variability and diversity of nature and the unforeseeable evolution of existence in time into more constant patterns. This helps human’s mind to maintain a certain control over the changing flows of life. The idea of symmetry has long been applied in the arts and architecture, especially when mankind’s position in the natural context was more precarious than it is today.

Both Raffaello and Mondrian were well aware that nature and human existence are a combination of infinite and finite, disorder and order, asymmetrical and symmetrical. However, in the 16th century asymmetry was subjected to symmetry, disorder to order, infinite to finite, nature to man and this, as we said, just to increase through culture a weaker position of mankind in the natural context. In the meantime, the situation has changed to the point that it is mankind today who has to take care of nature.

Through a constant alternation of same colors, the symmetrical sequences of Broadway Boogie Woogie arise within the lines, become planes which convey for a moment a sense of constant and finite space and then dissolve back into mutable, virtually infinite lines.

From this point of view the symmetrical sequences symbolize the birth of human thought (based on finite and measurable space and the need for a certain order) emerging from an asymmetrical, unordered, infinite natural universe symbolized by the endless lines. In other words and as obvious as it may sound, mankind and thought are generated by the natural universe. Thought is generated by nature, reflects on it, and then flows back into the natural universe.

If in Raffaello’s time a general symmetry of the whole composition tended to enclose the natural universe, in our time human thought (science) tends to capture only more or less extended sections of the natural totality (the symmetrical sequences along the lines).

The Natural generates the Spiritual

Broadway Boogie Woogie shows that what Mondrian defined as the Natural and the Spiritual are one and the same “thing”. The awareness of the ever-changing multiplicity and unpredictability of existence (the Natural) and the human need to reach for more durable syntheses (the Spiritual) appear to be opposite and irreconcilable if considered from a static point of view but reveal equivalence when considered as parts of a same process that transforms one aspect into its opposite as shown in Broadway Boogie Woogie.

Just to make an example: black and white are opposites. Between black and white there is an infinite range of grays and if we could really contemplate every single infinitesimal degree of that range, white would progressively become black. From this point of view, the idea of opposites seems to be a sort of escamotage of human’s mind to condense the infinite variations of nature (such as the one between white and black) into the shortest possible interval which therefore becomes easier to handle.

If we observe nature with a spiritual gaze, it evokes unity, and if we observe it with the analytical gaze of the sciences, nature never ceases to multiply, shattering the sense of unity invoked by the spirit.

Rational thought analyzes, creating an endless multiplicity, what the spiritual soul perceives as an inseparable whole. It is also true that even science seeks to achieve synthesis through the formulation of unifying laws that explains phenomena so far treated by individual disciplines, but in its operation at a particular level, analysis often loses sight of the synthesis.

In plastic terms Broadway Boogie Woogie exhorts us to contemplate multiplicity as one and then return to consider the one as an infinite variety when the unitary plane re-opens to the multiplicity of small squares and opposite lines.

Edgar Morin speaks of: “continuous comings and goings between the parts and the whole”. Each individual thing is at the same time one and multiple according to how we observe it.

Genesis of space-time

Mondrian writes: “The straight line is the plastic expression of maximum speed, maximum energy and therefore leads to the abolition of time and space.”

Every Neoplastic line symbolizes thus an absolute entity with no space-time. The meeting of two opposing lines generates in Broadway Boogie Woogie small squares which are fragments consisting of a horizontal and a vertical part. The small squares are a relative entity if compared with the absolute line (either horizontal or vertical) they are part of. The small square is a relative entity of a certain extent of space that lasts an instant of time within the line. The small squares therefore symbolize in Broadway Boogie Woogie the birth of space-time.

The small squares join in symmetrical sequences which then generate larger areas of color that, in turn, grow in size until they reach their maximum extension with the plane that unites the three primary colors. The increase in extension of space implies a relative increase in the duration of time. Broadway Boogie Woogie makes visible in plastic terms the birth and progressive consolidation of space-time.

Our space-time and a universal space-time

Science made us aware that our sense of space-time is only a particular case of a universal space-time (micro and macrocosm) that does not necessarily always respond to our coordinates. Before and after the interval which constitutes our reality, universal reality no longer responds to our sense of space-time.

“Time is real for us. Beyond time is the true reality, but not our reality. By means of our reality we have to come to the true reality. Hidden more or less by our reality, the true reality is always present. Progress is unveiling of the true reality.” (Mondrian)

The notion of space-time that we experience in a completely spontaneous way (to the point that we cannot imagine anything different) is, in truth, only part of a more extended and variable sense of space-time. Particle physics is investigating this extension and not infrequently is faced with events that cannot be described by our current way of thinking.

“That which is outside of time and space is not unreal. If at first it is only an intuitive concept, it becomes real as our intuition becomes purer and stronger. The new plastic is an intuition that has become plastically determined.” (Mondrian)

An elastic space-time

On observing the straight lines that, as Mondrian states, do not stop continuing, it is not possible to fix and isolate a finite portion of space that would last a certain interval of time. This becomes possible when two opposite lines meet and give birth to small squares which are finite and measurable entities lasting for an instant of time within infinite, timeless lines. When we say “timeless” we mean our sense of time.

The small squares form symmetrical sequences, i.e., they tend to extend their finite nature within infinite lines; the symmetrical sequences grow into larger planes; this implies an increase in finite space and time duration which finally reaches the maximum with the largest unitary plane. At this point the unitary plane begins to dissolve. This means that our sense of time shrinks again returning to the instantaneous situation of small squares and then to the virtually infinite, timeless lines. This means that our common notion of space-time dissolves turning into the space-time of the infinitely small (microcosm) and the immensely large (macrocosm), i.e., into a universal space-time the never ending lines are a symbol of.

We see here another fundamental difference between the two ancient frescoes and the modern painting. In the two 16th century works, mankind and his sense of space-time is the measure of everything; the 20th century work, on the other hand, shows the absence of space-time (the infinite lines) from which our space-time is generated (squares / symmetries / planes) that then returns towards a universal space-time. We could talk of an “elastic” space-time.

The “supernatural” is still nature

This clearly shows the overcoming of the concept of nature as the only part of phenomena that we actually perceive (evoked by so-called realistic or figurative painting) and its extension to the infinite variety of phenomena that make up the microcosm and macrocosm our reality is part of, that is, to a wider reality.

As long as man considered himself the measure of creation, reality had necessarily to coincide with what he is given to see. For a long time and even today we believe that what appears to our senses is the whole reality while the rest has been defined as metaphysical; beyond; supernatural.

Ascertained through science that what we see is only a part of reality, the “beyond” becomes a “here and now”; a reality that we do not see but that is just as real and substantial component of everything we see. The so called “supernatural” is beyond that part of nature that we can perceive but is still nature. There is nothing surreal in all this but only a healthy update of our concept of reality.

How could painting express this broader picture except by abstracting from the limited part of reality which appears to us?

In extreme summary, we can define the Italian Renaissance as an extension of the concept of reality in force until the end of the 14th century when, to give just one example, the sky was often painted gold.

In the course of the first half of the 20th century there is a further realization of how nature really is. i.e., no longer just blue skies, green mountains and red apples. From this point of view, the process of abstraction pursued by Mondrian seems to be in tune with the Renaissance spirit aimed at observing and depicting reality in its full extent and true essence. This type of abstract art unveils true reality.

Leonardo da Vinci

“The senses are terrestrial, reason is beyond them when it contemplates” wrote Leonardo da Vinci. In this affirmation I see an implicit reference to a vision intuited by reason that goes beyond the most immediate perception of the senses. Leonardo said that “painting is innate to the visible” adding, however, in another note that “painting is a mental activity”. It follows that the painter must take into account not only what he sees, that is, what appears to the senses, but also what, according to reason and intuition, nature really is.

“Art must look not at the appearance of nature but at what nature really is. If we wish to fully represent nature, we are forced to look for another plastic expression. And it is precisely out of love for nature and reality that we avoid its natural appearance” (Mondrian)

Having said that, painting is and remains a question of beauty, harmony, equilibrium, pleasure of the eye that satisfies the mind.

It is all about proportions

Mankind’s questions about the essence and eventual purpose of nature and human existence also arise from our finite dimension compared to a universe which is infinite. Any religious, philosophical or scientific theory seems to me sophisticated attempts to rebalance the disproportion between mankind and the universe and what, if not the art of painting, can deal with proportions?

In the past, painting dared to engage with the universal. I believe that once the anomalous wave of certain “contemporary art”, which has been abusing our patience in the recent past, has passed, art will be able to resume its journey towards new, more serene and convincing horizons.

Express the imprecise with maximum precision

The plastic means used by Mondrian (straight lines and defined planes of primary colors) constitute a precise language that evoke the clarity and determination of rational thought; nevertheless, the precision of the expressive means does not preclude in this case the possibility of dealing with what is commonly considered imponderable or mysterious.

Italo Calvino comes to mind when he says: “Expressing the imprecise with maximum precision” and I think of Vito Mancuso when he writes: “(…) rationalism that reduces reality to the limits of human reason, excluding from the horizon of truth all that human reason cannot conceive and ending up depriving reality of every mystery and every depth. Against such a narrowing of rationalism, spiritual dialogue exalts the opposite perspective of rationality, which aims at a continuous opening of human reason towards the much broader logic-lógos of reality.” This is tantamount to saying that multiplicity becomes one and the one reopens to the multiple and this is what Broadway Boogie Woogie shows us.

Art must make us taste nature eternal

The infinite multiplicity of forms and colors that nature, often fleetingly, offers to our gaze is the fruit of the same, intimate and more enduring reality.

“Everything we see fades away. Nature is always the same but nothing remains of it, of what it appears. Our art must give the thrill of its duration, it must make us taste it eternal” (Paul Cézanne).

“Beneath the succession of moments, which composes the superficial existence of beings and things, cladding them with changeable appearances that soon vanish, one can look for a truer, more essential character, to which the artist will cling in order to give a more lasting interpretation of reality.” (Henri Matisse)

This is where the process of abstraction began in European painting. A process that through Cubism found its first, fundamental achievement in the work of Piet Mondrian.“

“What is the particular value of abstract art that distinguishes it from the art of the past and from naturalistic art? That it is a direct, stronger and purer expression of life. What do we mean by life? Not the repetition of changing events but life itself, that is, the vital energy present in all of us.” (Mondrian)

“Art must look not at the appearance of nature but at what nature really is” (Mondrian)

Full and empty space

Reality, as it appears, induces us to see the space around us split between “full” and “empty”. We call empty space what is in between visible and tangible things. In reality we all know that it is not so. Everything is full and the “void” appears to us as such only because it is formed by energy-matter with a different density from what appears to us as full.

The colors of Broadway Boogie Woogie are white, gray, yellow, red and blue. In this progression we proceed from the lightest (white) to the darkest (blue). White suggests invisible, “empty” space while gray, yellow, red and blue progressively express “full” space. White evokes an ethereal space while yellow, red and especially blue suggest solid and heavy portions of space.

Gray appears as a first hint that from emptiness (white) proceeds towards fullness. Emptiness (white) acquires consistency (gray) and consolidates into full and clearly visible forms (yellow, red and blue). From the ethereal to the more solid; from the indistinct to the definite; from the invisible to the visible.

The most solid and clearly visible area of space is the plane where yellow, red and blue reach unity. The white space to the right of this plane has the same proportions as the plane itself. In that way the painting tells us that fullness is equivalent to emptiness, the visible has the same importance as what is for us invisible:

During the elaboration phase of the Neoplastic language Mondrian considered white, grey and black as colors symbolizing the spiritual while yellow, red and blue were a plastic symbol of the more lively and contrasting variety of colors present in the real and concrete world.

The use of gray

Mondrian’s use of gray in Broadway Boogie Woogie is also interestingly reflected in Raffaello’s La Disputa del Sacramento.

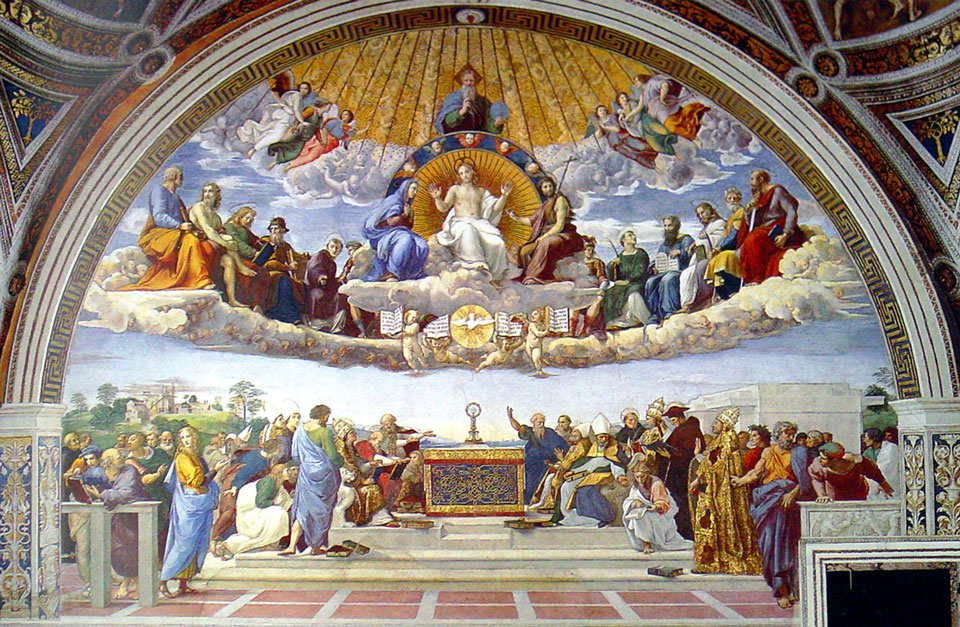

The passage from the real earthly scene to the metaphysical one that develops higher up takes place through a semicircle of white-grey clouds in which we can glimpse figures of angels that, compared to the well-defined figures of the earthly characters, appear almost as incorporeal entities interconnected among themselves:

From the central circle with the dove of the Holy Spirit, space expands towards the sides, first with the four more defined angels showing the Gospels and then with the more ethereal angels at the base of the figures of saints and prophets. What is an angel if not a metaphor for spiritual energy? Through the angels mixed with clouds, the Holy Spirit (solid and well defined in the center) radiates into those wise and holy men.

Here too, therefore, the colors white and gray express something ethereal and indistinct, while yellow, red and blue tones express most of the garments of the earthly characters, that is, something more tangible and concrete. White plays a similar role to gray even higher up, just below the golden canopy, where a trail of clouds can be seen in which incomplete silhouettes of waving angels can be glimpsed, while on the right and left are two groups of three angels each.

Ethereal and solid

In both the ancient fresco and the modern painting white and gray express a more ethereal matter than the solid, full-bodied yellow, red and blue.

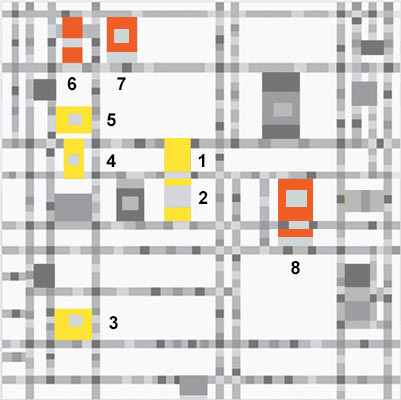

In Broadway Boogie Woogie some phases of transformation of space appear in gray precisely those in which the process of internalization of space begins (Diagram C – 1 and 2), which continues with 3, 4 and 5 reaching the largest extension with 7:

With 8 the gray color again signals a process of metamorphosis.

The phases of transformation from the outside to the inside (from 1 to 7) and then from the inside to the outside (8) are gray because gray is the color closest to white where everything appears indistinct.

For both painters white and gray seem to express energy in a fluid state while yellow, red and blue express the same energy that has consolidated into matter.

back to past and present

Copyright 1989 – 2024 Michael (Michele) Sciam All Rights Reserved More