Please note: If on devices you click on links to images and/or text that do not open if they should, just slightly scroll the screen to re-enable the function. Strange behavior of WordPress.

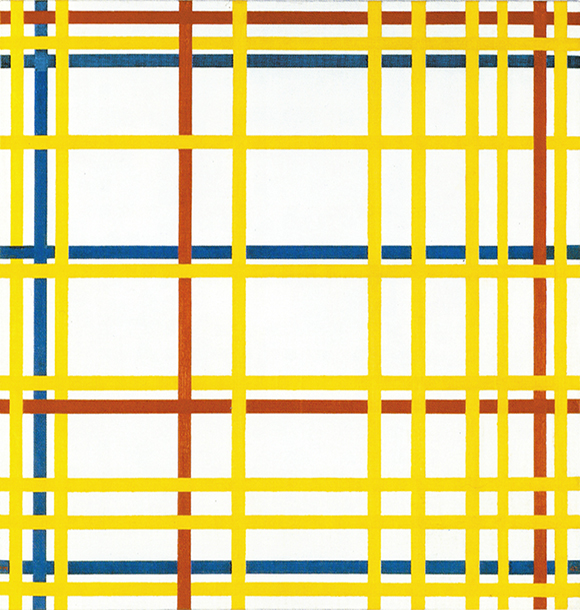

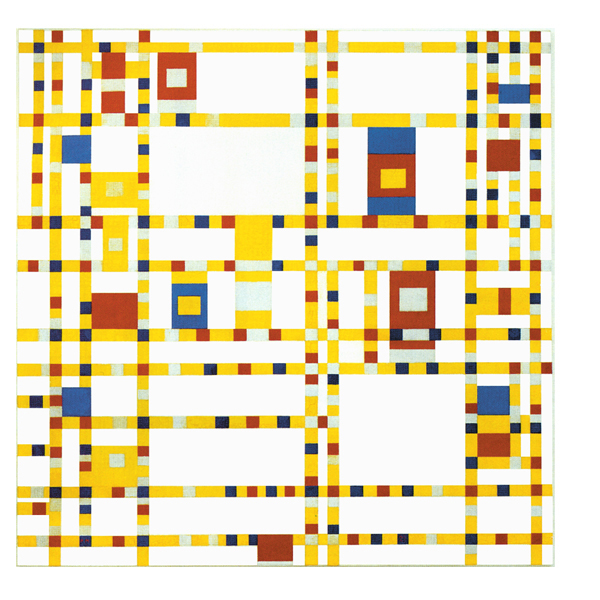

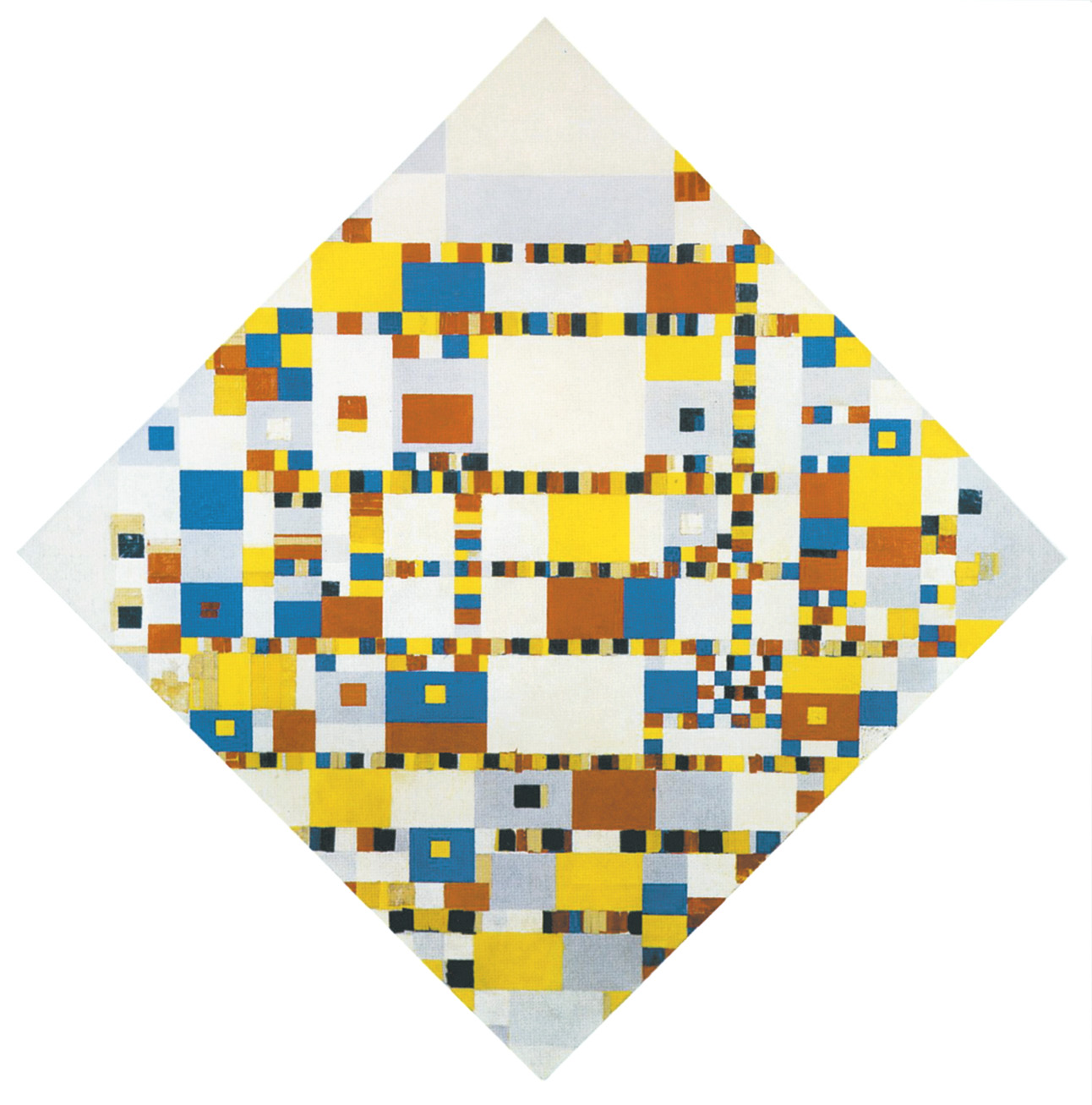

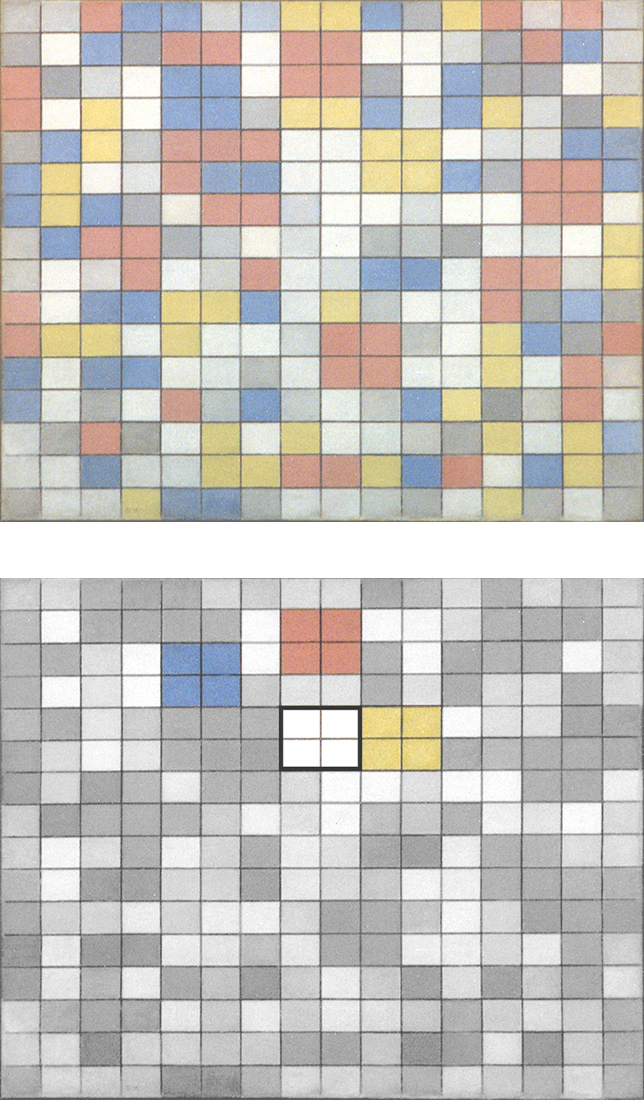

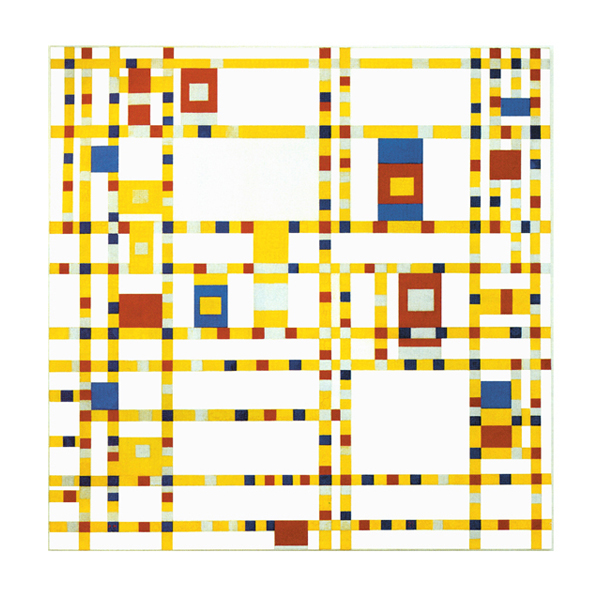

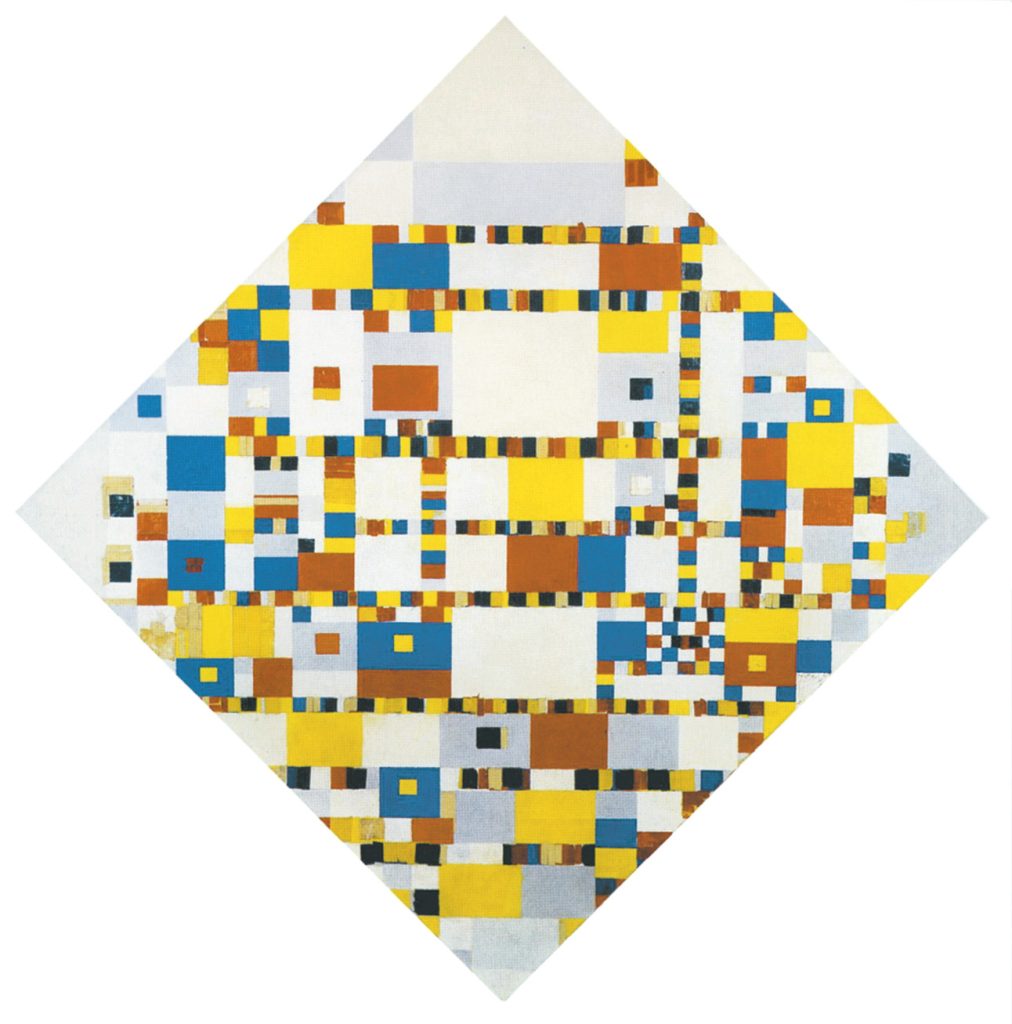

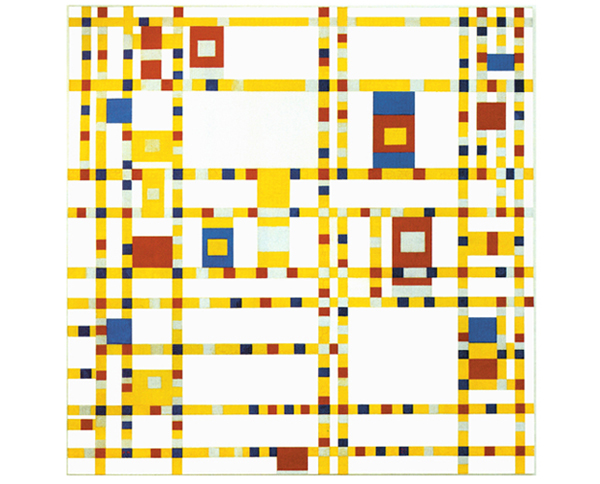

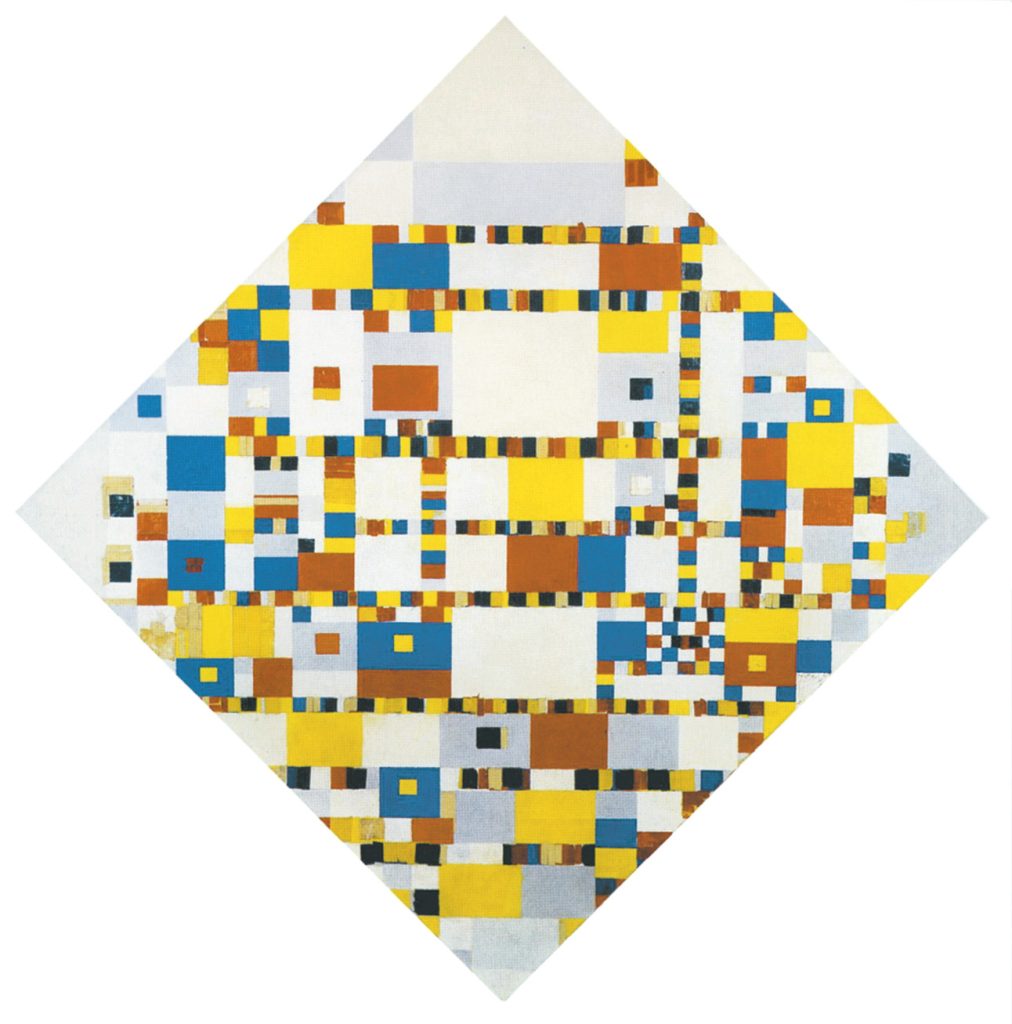

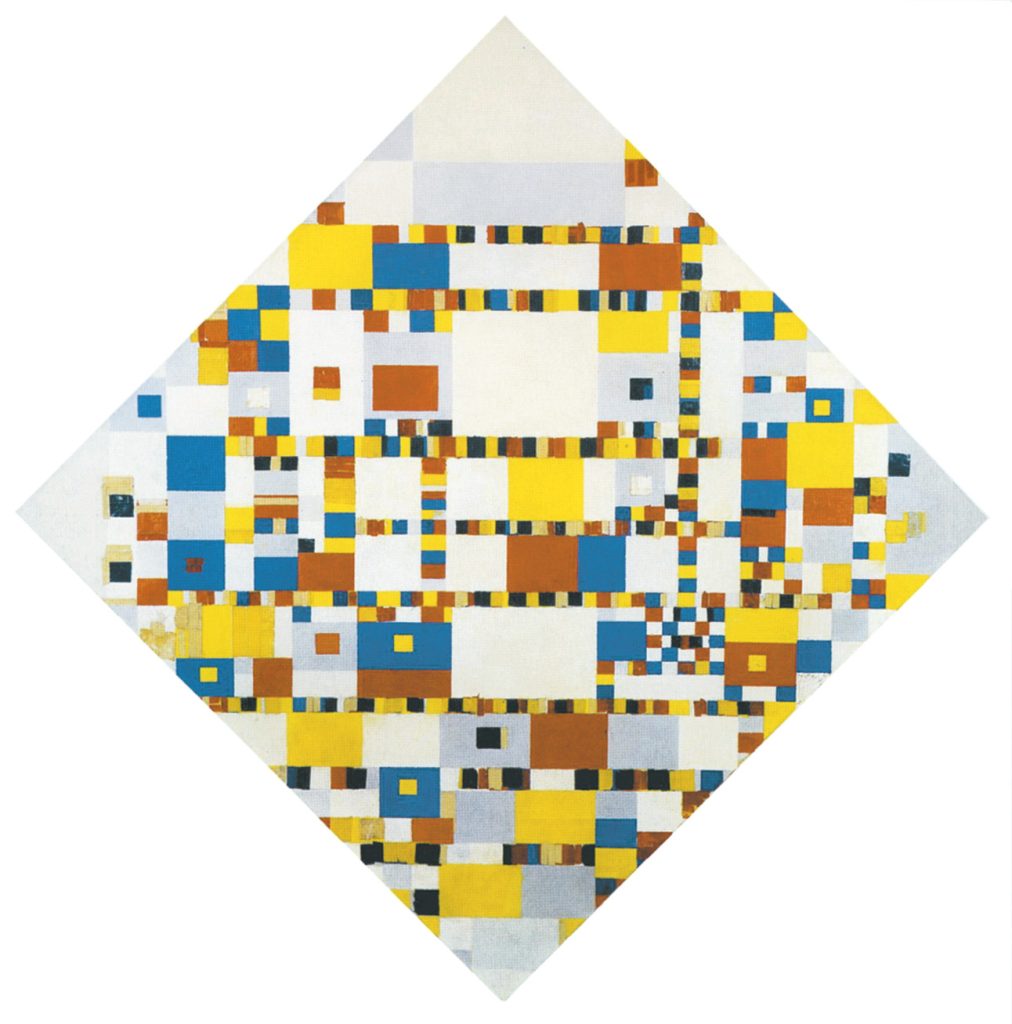

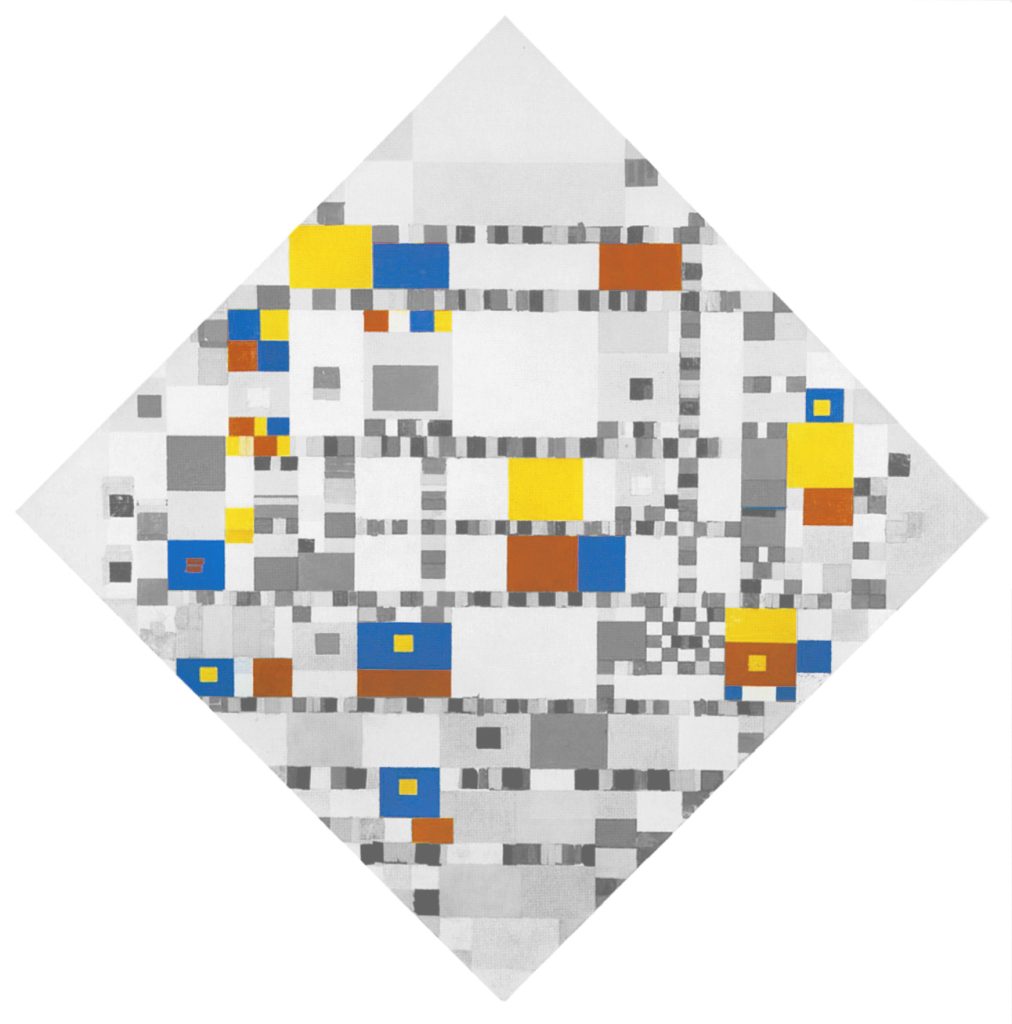

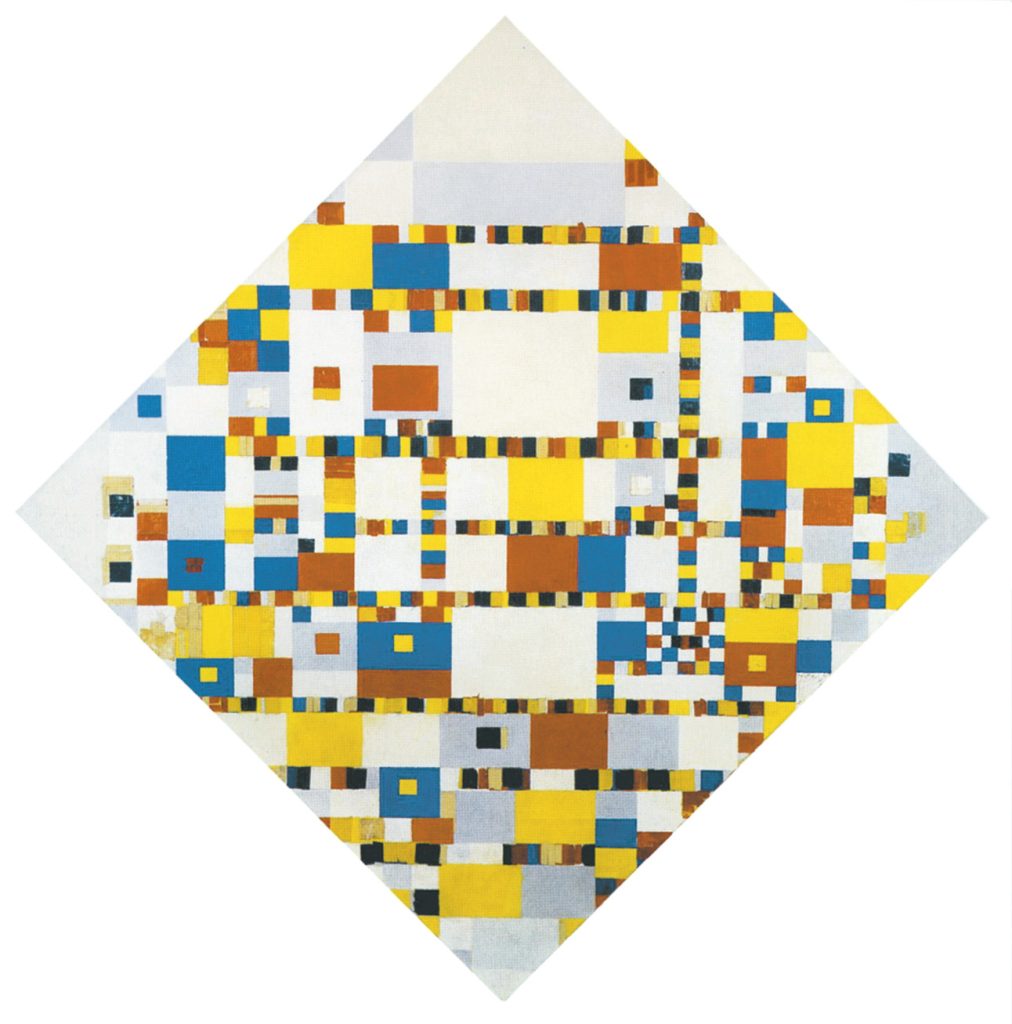

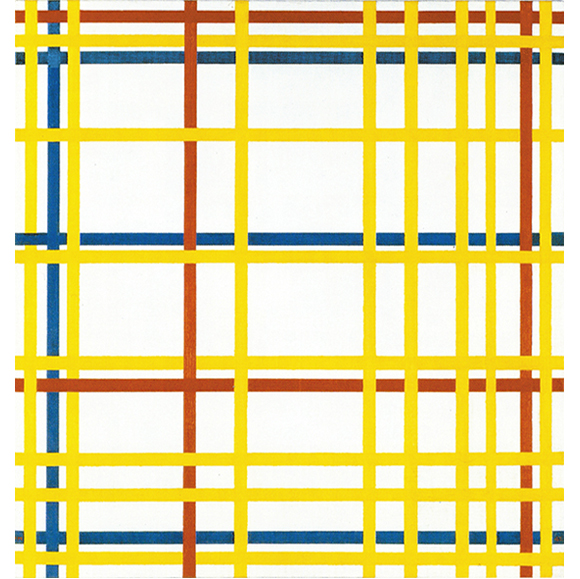

We examine here the second last canvas that Mondrian worked on at the same time as Broadway Boogie Woogie and that was to remain unfinished upon the artist’s death in 1944 after various episodes of reworking.

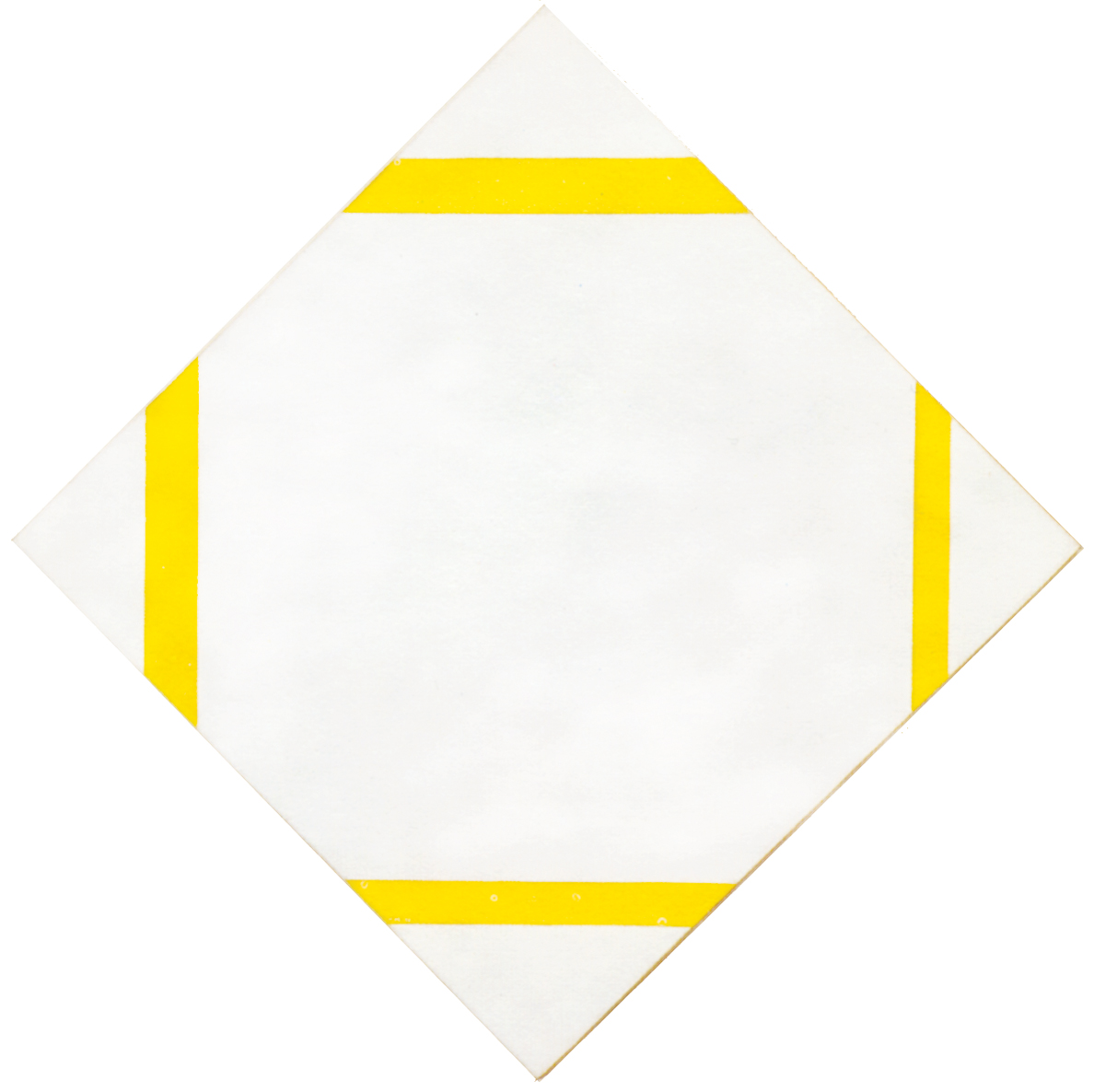

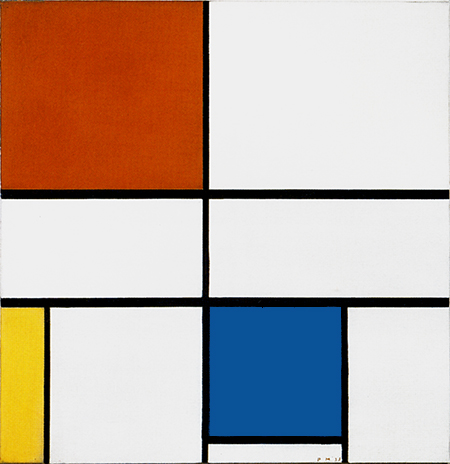

Oil and Paper on Canvas, cm 126 x 126

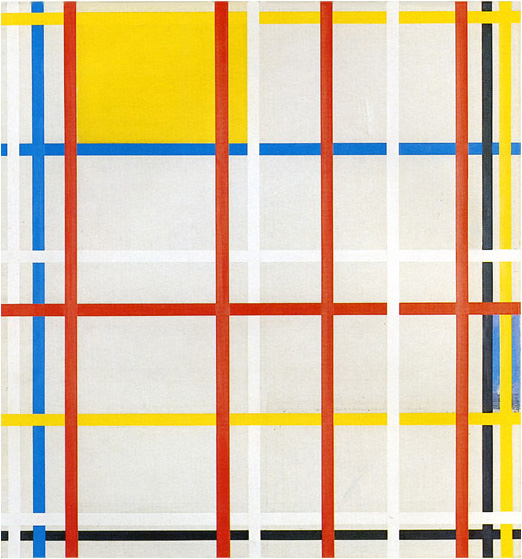

It should again be stated (for lovers of dates) that Mondrian appears to have begun Victory Boogie Woogie, (from now on VBW) before Broadway Boogie Woogie (from now on BBW). As in other periods of his development, however, the dates on which individual canvases were begun and completed do not coincide with the progress actually achieved, which it is our present concern to indicate and explain. I regard BBW as coming immediately after New York City and VBW as a continuation of BBW. My grounds for this will be stated below.

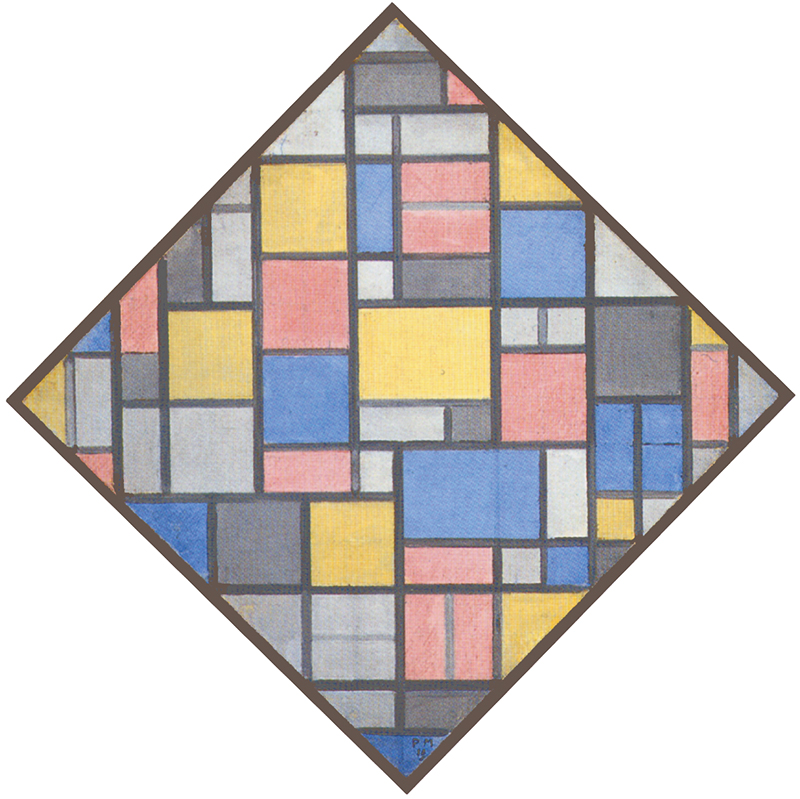

The canvas is the same size as the one used for BBW but this time in the lozenge position. What characterizes the composition at first sight is a further increase in multiplicity.

1942-43

1942-44

Another significant difference with respect to BBW consists in the almost complete absence of continuity in the lines, which are reduced to seven horizontal and two vertical rectilinear sequences. The lines appear continuous in BBW because the space between the small squares is predominantly yellow. The rectilinear sequences of VBW are instead made up of a tighter rhythm of small, differently colored rectangles and squares, so closely arranged as to reduce the sense of linear continuity to the absolute minimum.

The infinite becomes finite

In BBW the planes are generated by the lines and return to them; in VBW lines and planes seem to become one and the same thing. While space is nevertheless quite dynamic (not least because of the lozenge format), its dynamism is the result of a virtually unlimited number of planes interacting with one another. While the finite dimension of the planes appears predominating now, their large number and variety suggest a virtually infinite space. The infinite space previously expressed through never ending lines is now expressed through a very thick space made of finite planes.

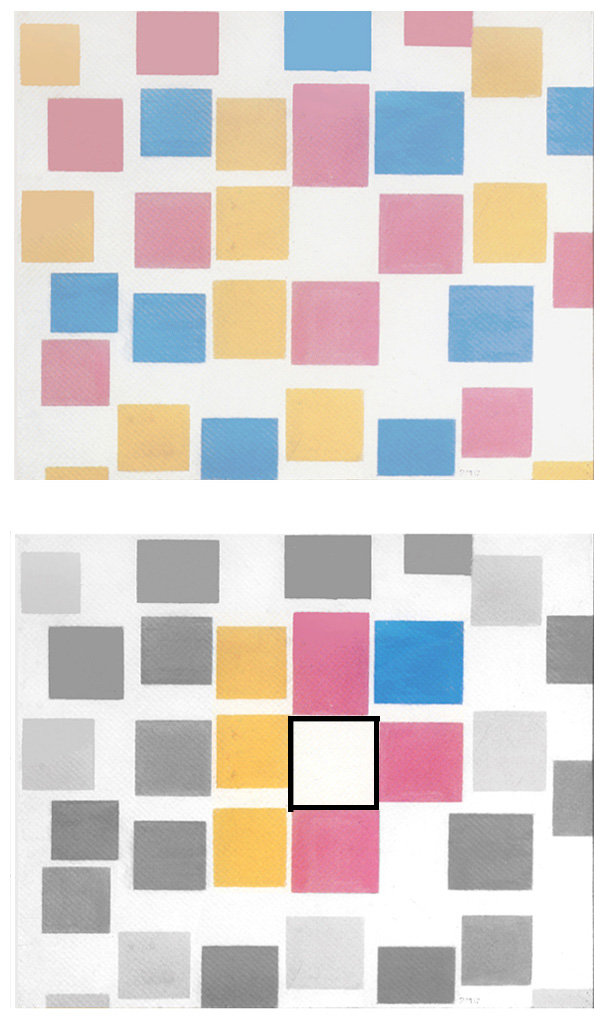

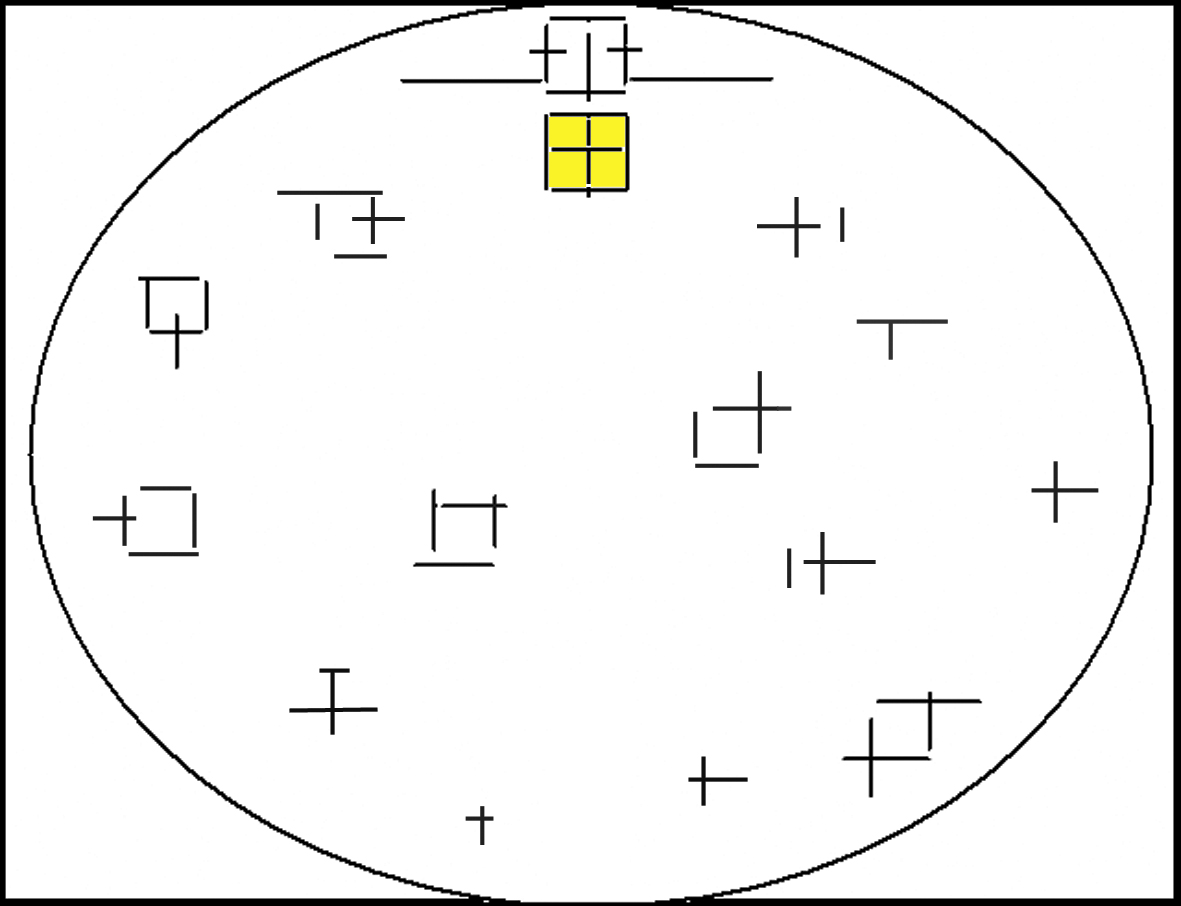

Everything varies in VBW, as it does in BBW, but we no longer see any process leading to a unitary synthesis. It is multiplicity that predominates here. VBW appears to present an endless sequence of potential syntheses of yellow, red, and blue manifested in constantly varying forms which never reach a single defined unity as in BBW. (Diagram A):

Diagram A

In actual fact, this is precisely what BBW tells us: unity opens up to multiplicity. We encounter a great many instances of partial syntheses in VBW, but not one that holds for the composition as a whole as seen in BBW. The idea of unity is in VBW relative. Everything, in its own way, shows a tendency toward unity without, however, ever achieving it in absolute form. I am reminded of the multiethnic society of New York, where all cultures and all religions necessarily assume relative value.

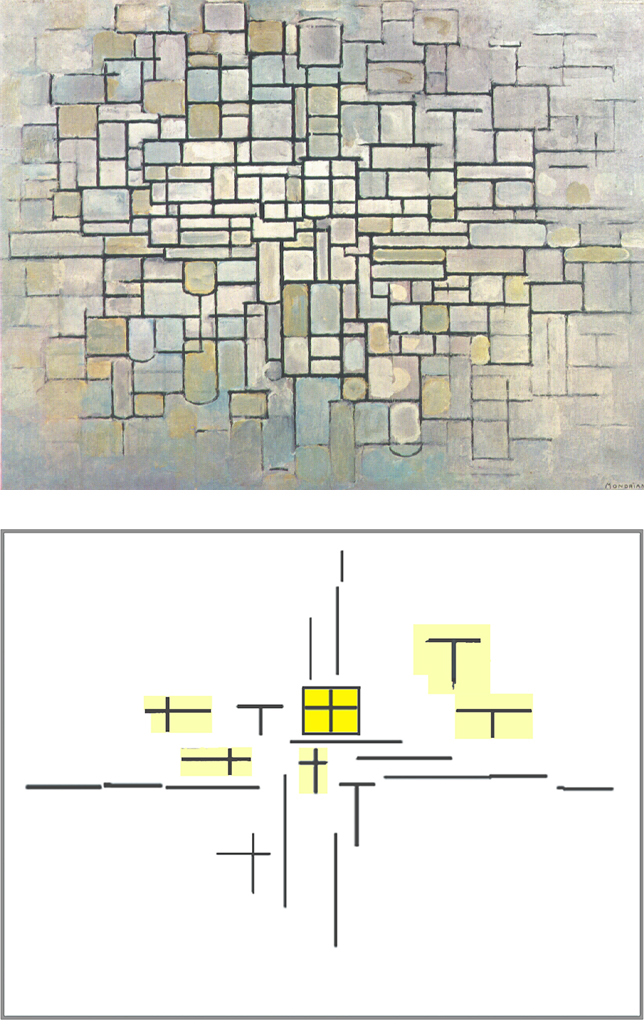

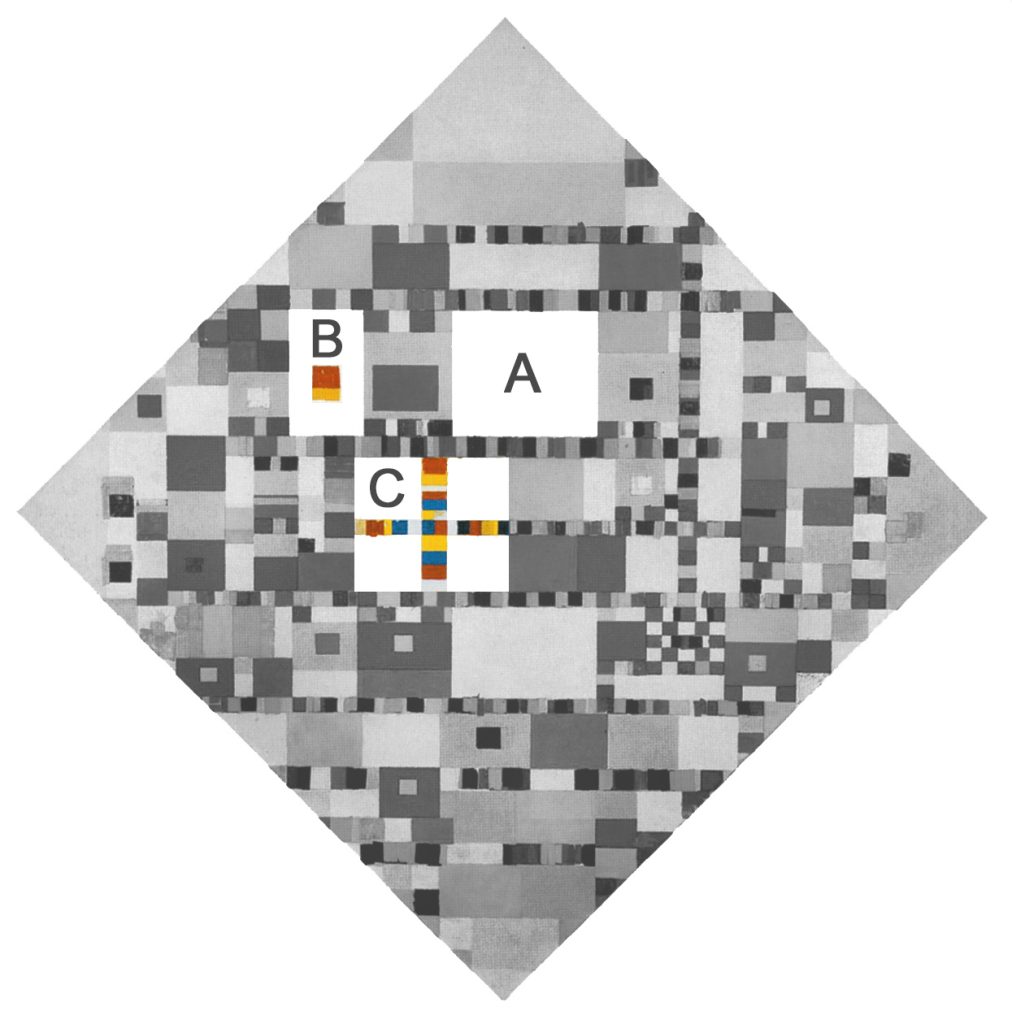

A white form verging on the square can be seen in the upper section (Diagram B labeled A):

Diagram B

On the left we see a white plane (B) (with the same proportions as the unitary synthesis of BBW) inside which two small notes of color (yellow and red) are born.

Inside a third white area (C), which is analogous in its proportions to square A, we see opposite linear sequences consisting of a multitude of differently colored fragments. The white synthesis we see in A becomes manifold in C. All the colors we see in C seem to blossom from white (A): first the two accents of yellow and red (B) and then the more substantial sequences of yellow, red, and blue (C).

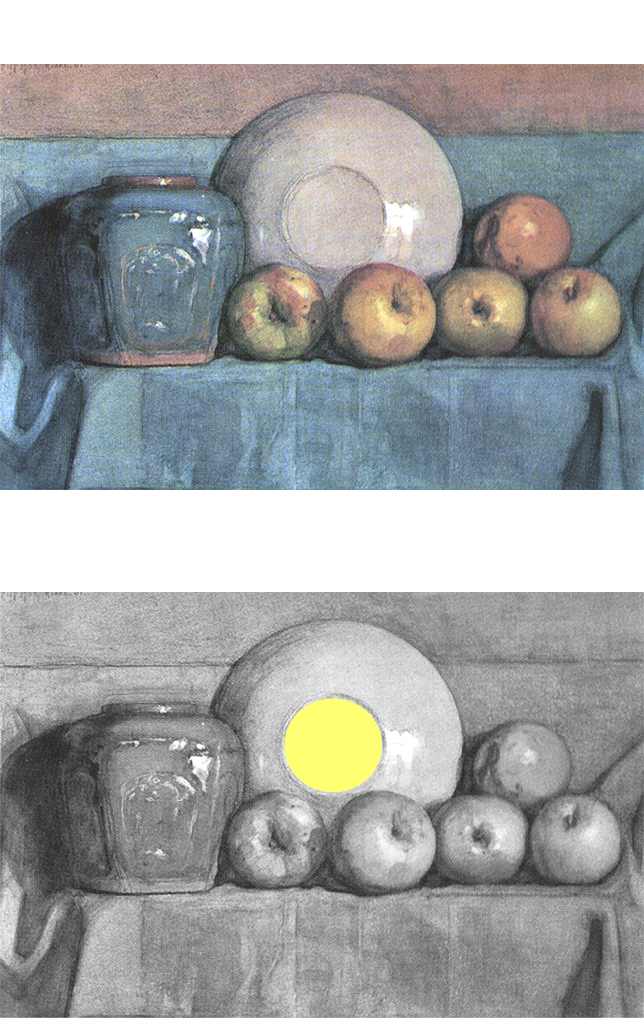

I am reminded of previous works where white was suggesting an ideal synthesis of all the colors:

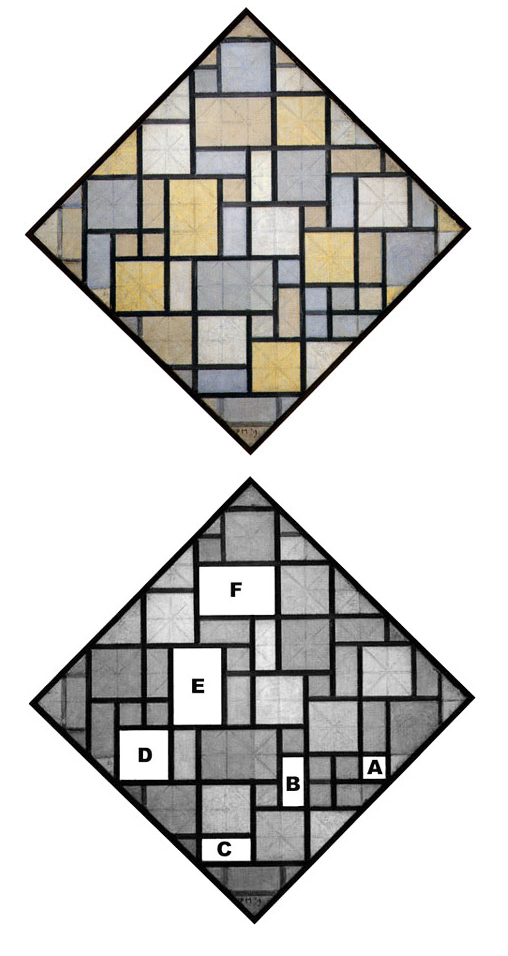

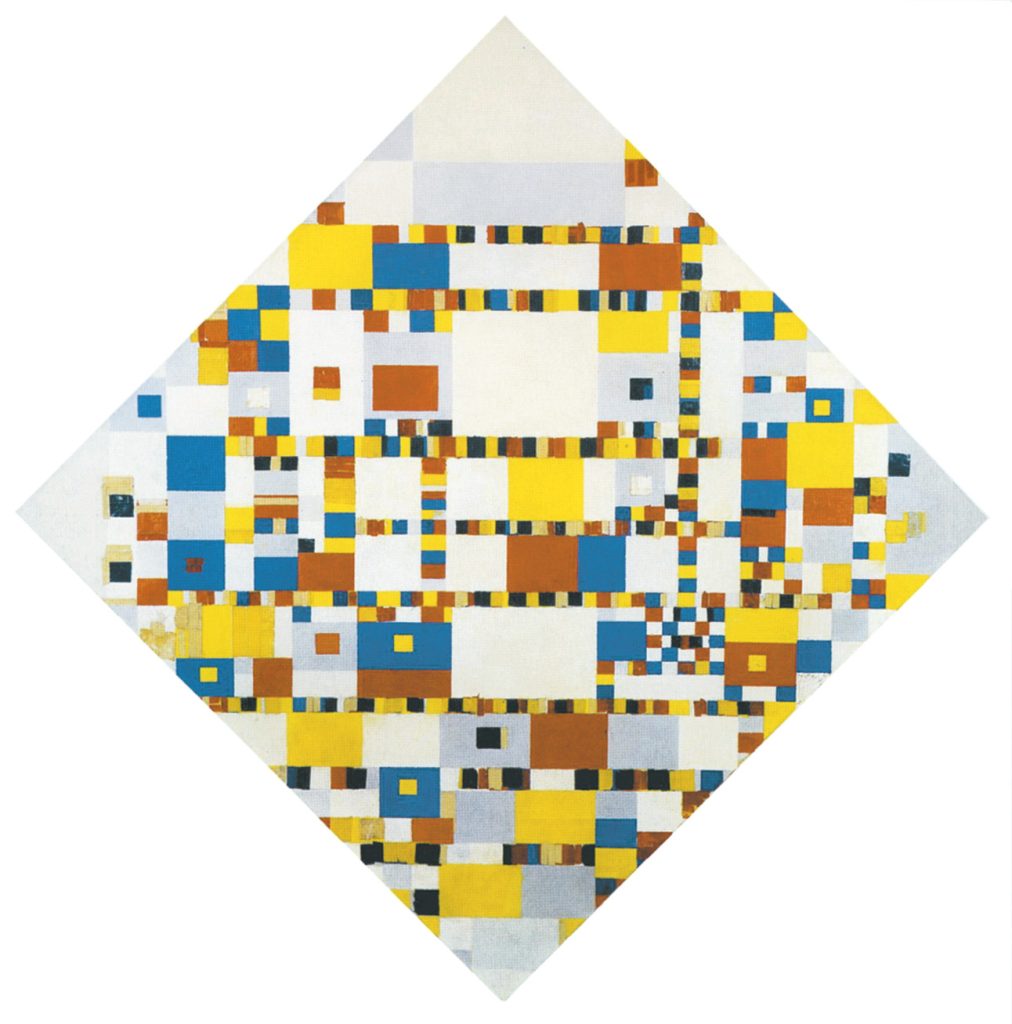

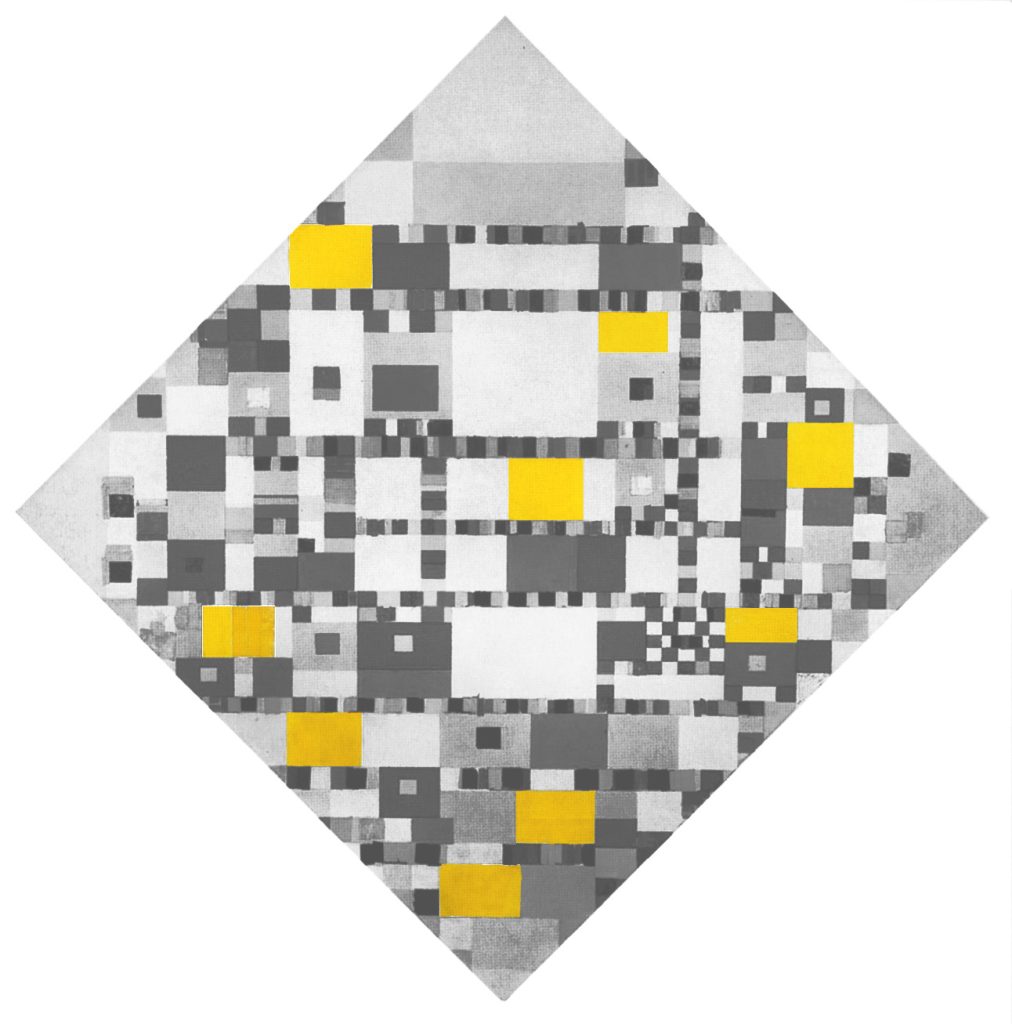

Going back to VBW, a quick view taking in the composition as a whole picks out a group of yellow planes that seem to evoke something more constant (Diagram C):

Diagram C

On closer observation, we note that seven out of the nine yellow planes present approximative amounts of color but vary in their proportions or present the same proportions but vary in terms of relations with the surrounding parts.

We are observing either different entities that are related to the same basic “pattern” or, vice versa, the “same” entity in a state of becoming, constantly changing in appearance; another way of contemplating the one and the many.

The artist shows us this broader variation of yellow in order to suggest that the variety he intends to evoke with his painting is in actual fact far greater than the canvas can display. It prompts us to imagine all the other different shapes, sizes, and proportions that white, gray, red and blue could assume in all the possible positions and reciprocal relations to one another: a truly infinite “landscape”.

To his friend Charmion von Wiegand, who visited him on January 17, 1944, Mondrian said that in Victory Boogie Woogie everything was in place except for the top part, which still needed to be reworked. A friend visited him to see the painting in progress and stayed late into the night, leaving Mondrian still working at four in the morning.

As noted above, VBW is characterized by the almost complete disappearance of lines, a crucial component of Neoplastic space all the way up to BBW. In VBW lines and planes become the same thing and the sense of multiplicity or totality previously expressed through the continuity of the lines now appears to be wholly concentrated inside the canvas. This has a precise meaning upon which it is necessary to reflect:

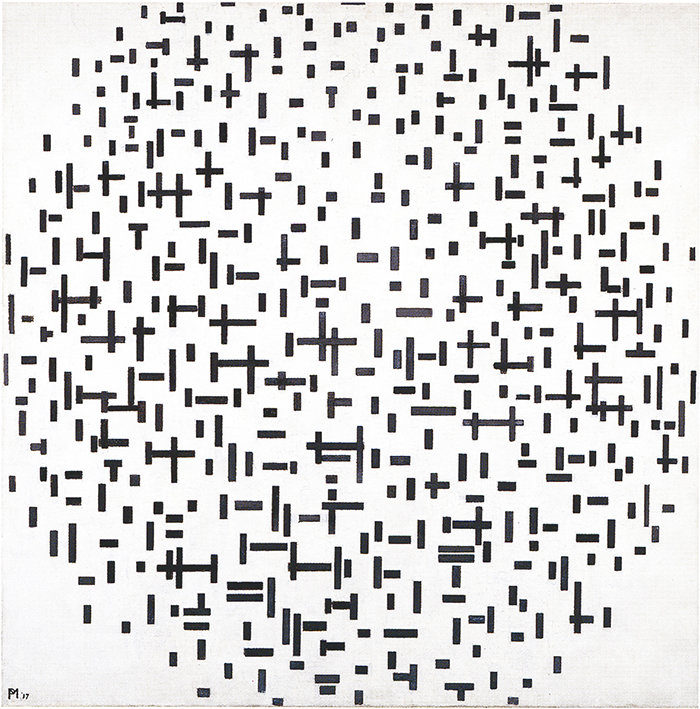

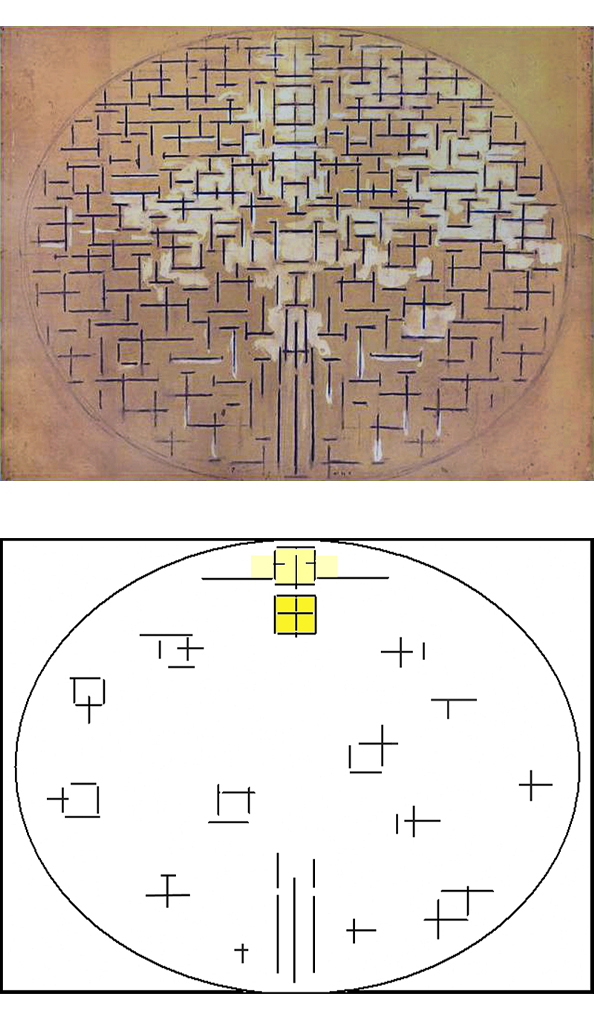

An oval turns into straight lines

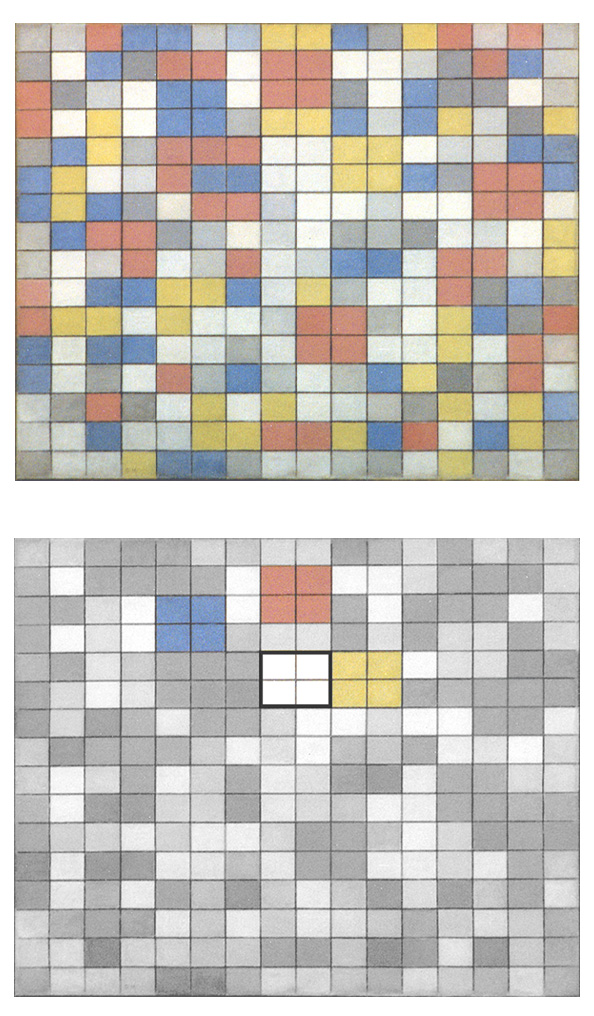

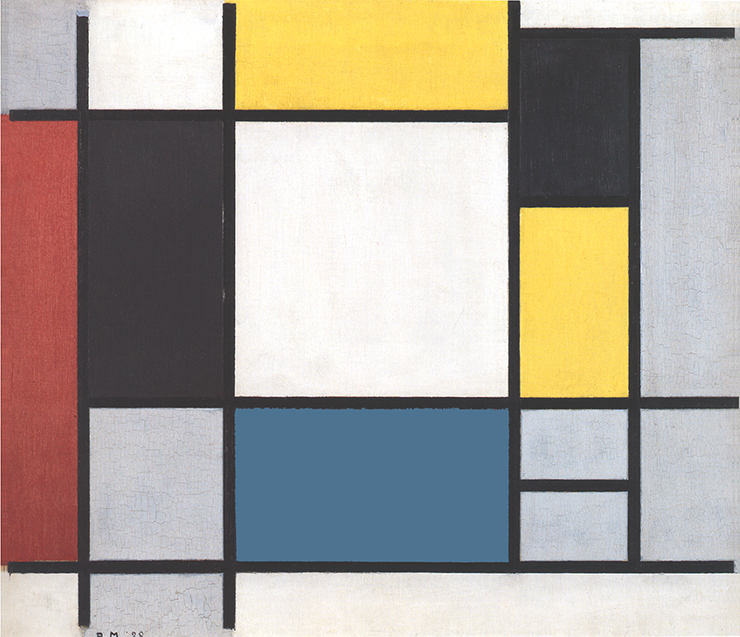

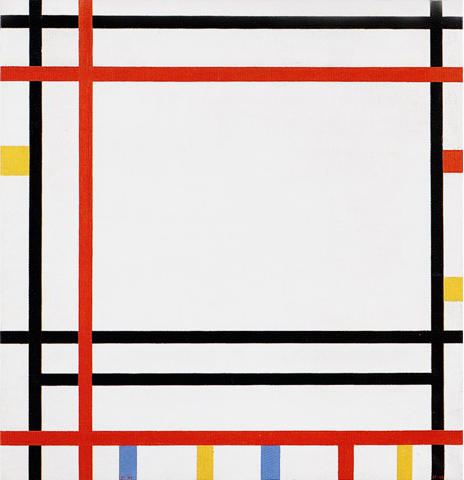

Neoplastic lines were born when the oval of the Cubist period (Fig. 1) expanded beyond the finite space of the canvas (Fig. 2 and 3)

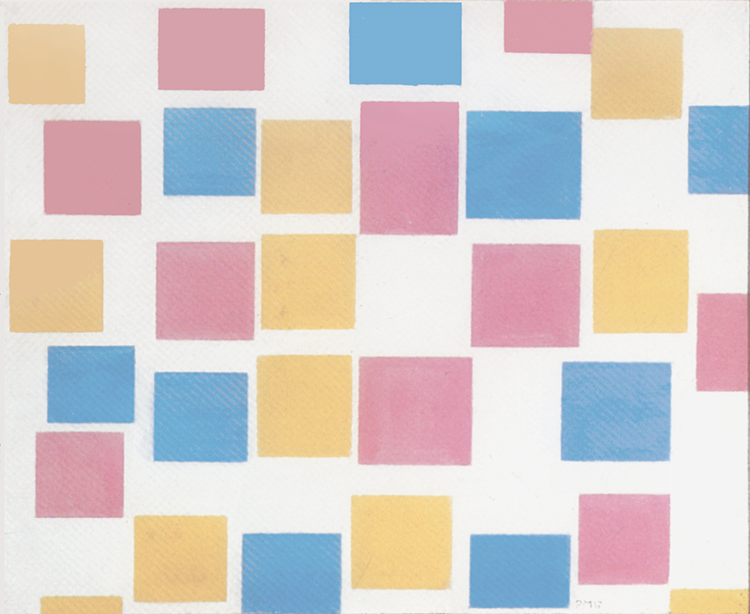

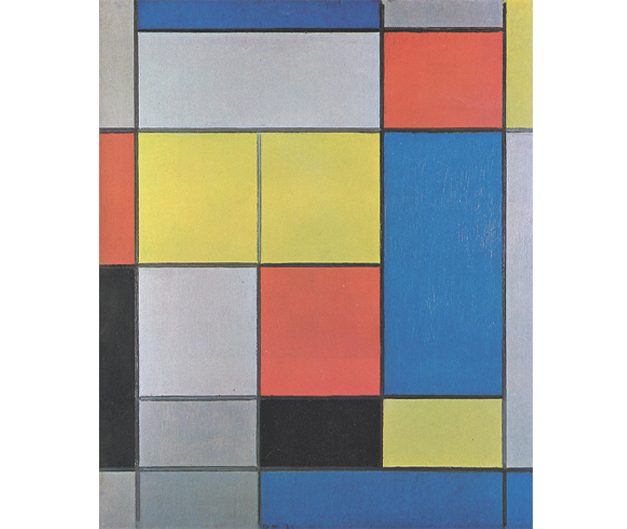

leaving within the painting a variety of colorful planes (Fig. 4) which joined to generate linear segments (Fig. 5) that then became continuous lines (Fig. 6):

The totality of space expressed by the oval as a whole within the canvas (Fig. 1) opened up and became a totality manifested through lines that continue uninterruptedly (Fig. 6).

An idea of totality conceived in a metaphysical form (the oval), gave way to the assumed totality of real space, to which the canvas belongs and the virtually endless lines allude.

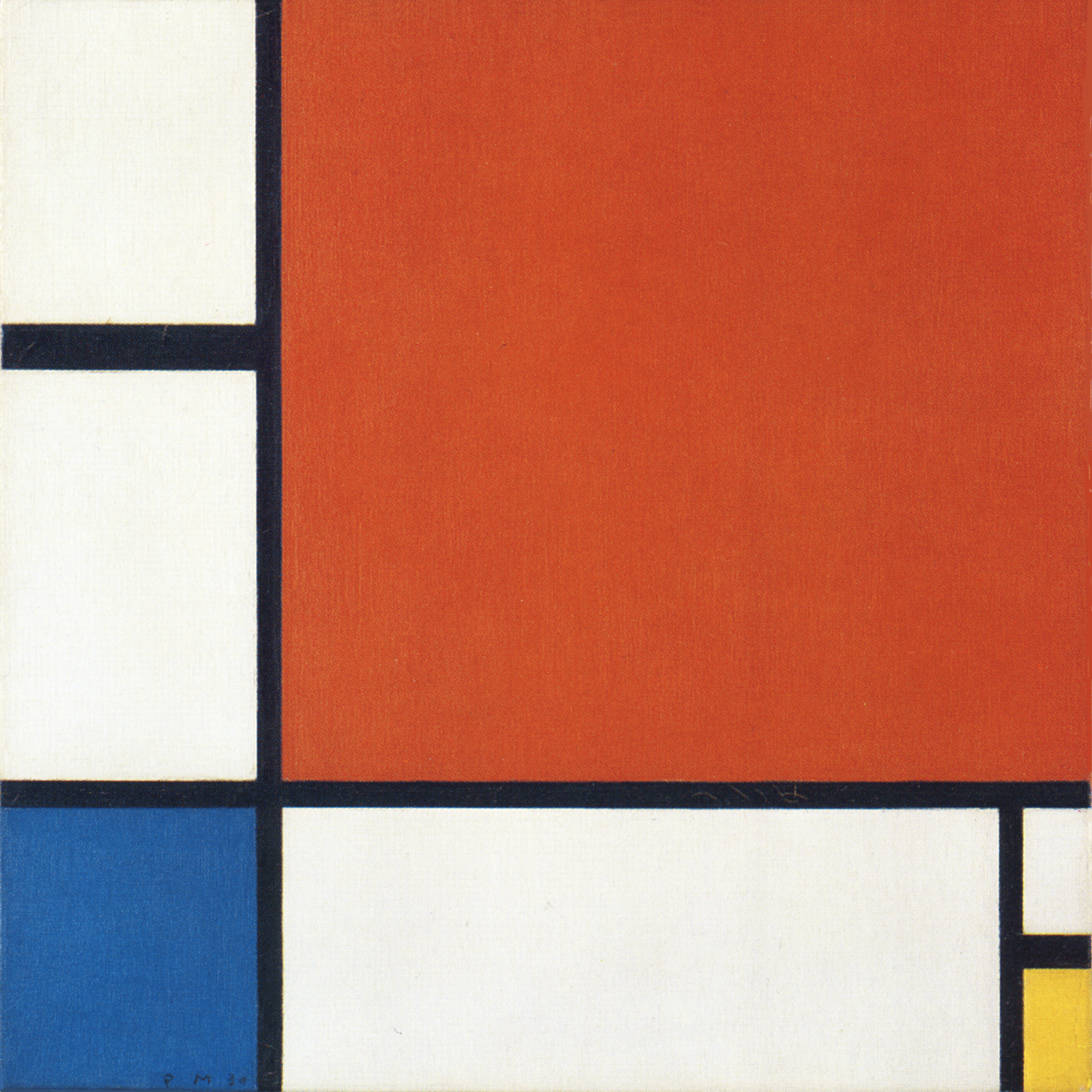

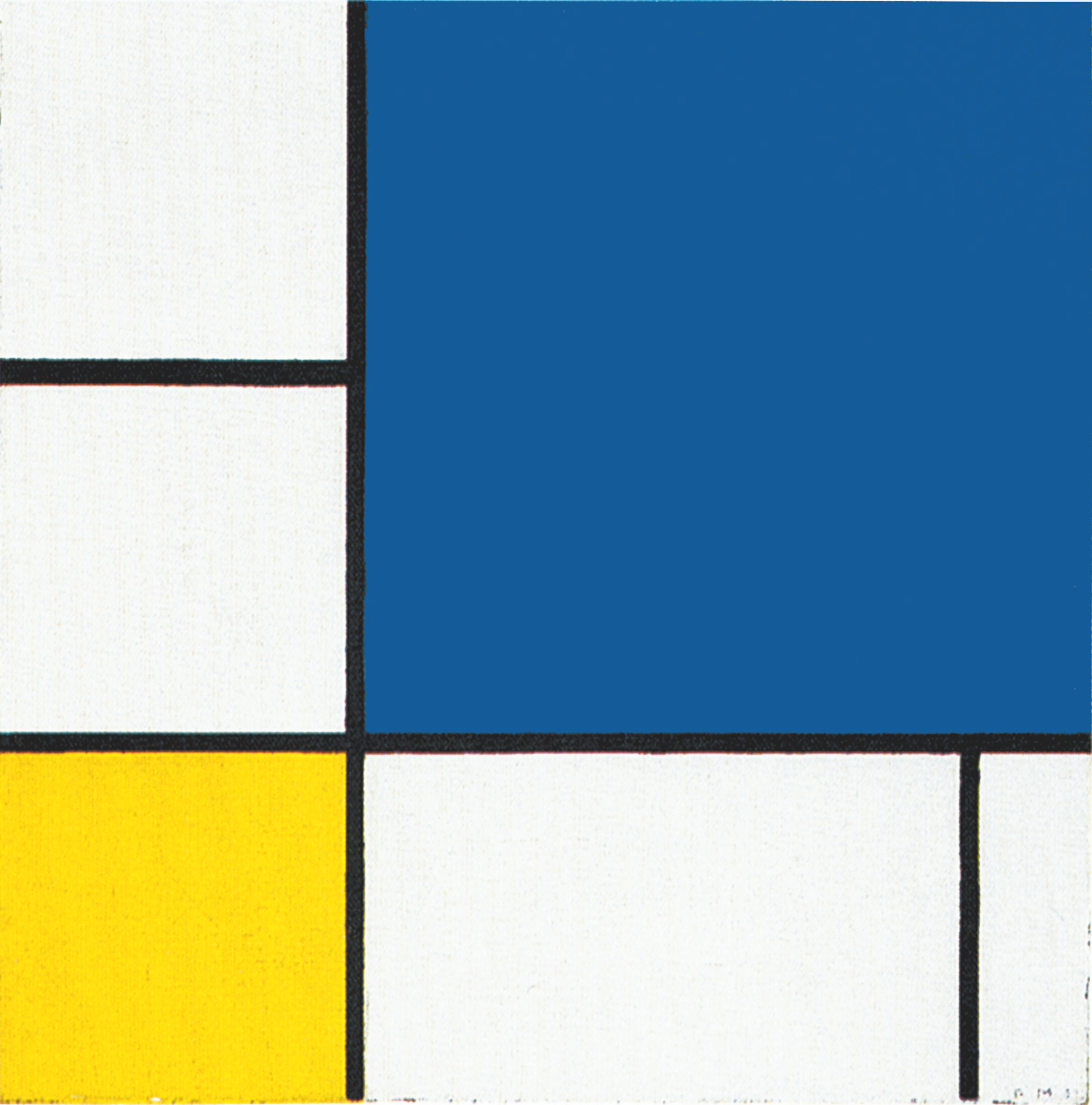

As from 1919 the manifold aspect of space underwent constant reduction (Fig. 6 to Fig. 11):

Mondrian’s Neoplastic compositions attained greater synthesis during the 1920s because the artist perceived the continuity of the lines as a means to ideally connect the limited space of the canvas with the infinite space of reality.

The lines performed the vital function of maintaining a link between the finite space of the painting and the infinite and multifarious space of reality.

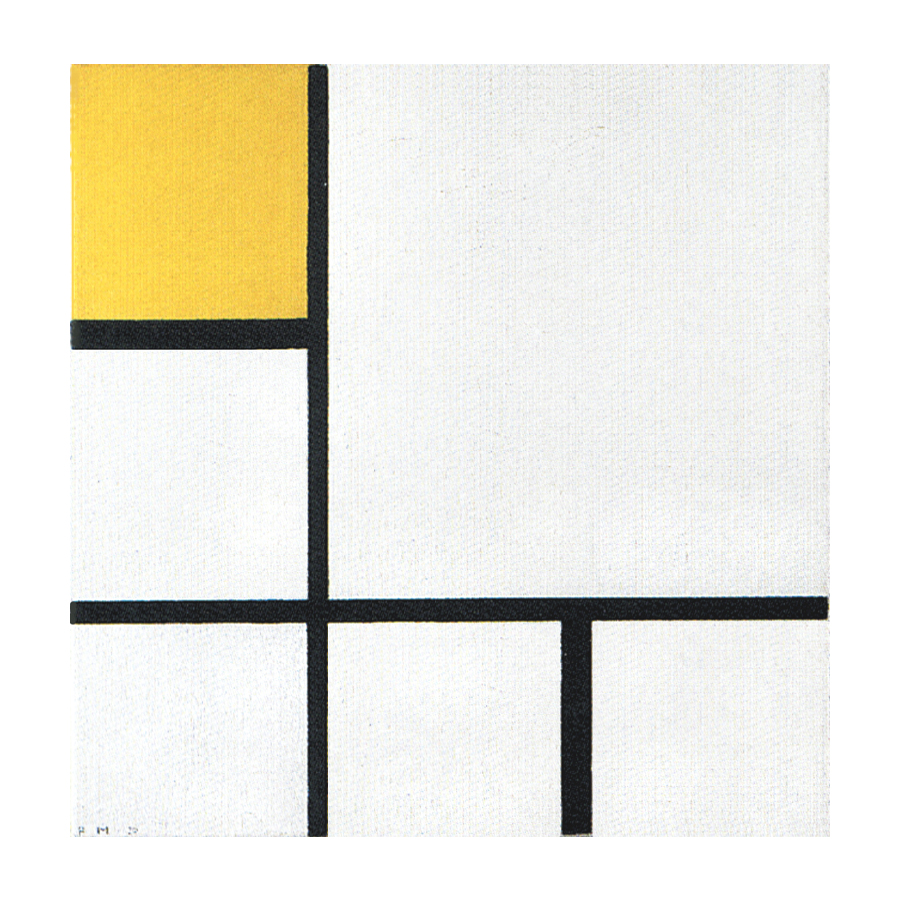

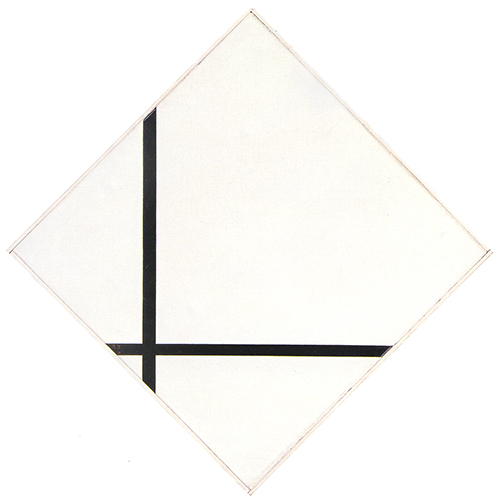

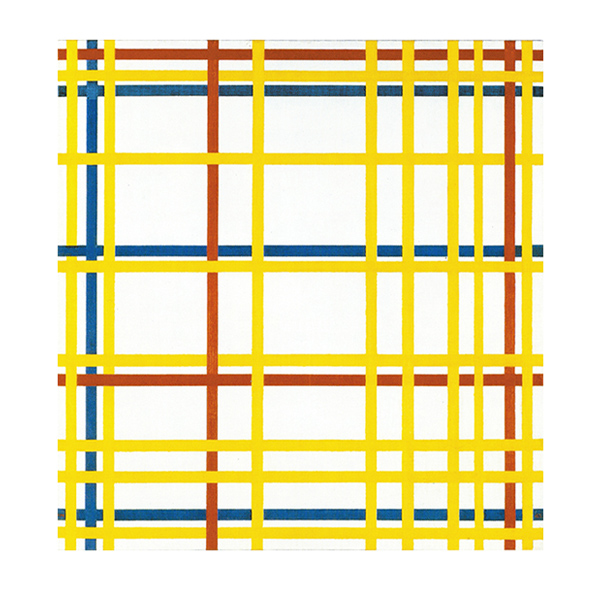

The compositions attained greater synthesis up to the point where everything was expressed by means of four yellow lines that differ from one another in slight variations in thickness to make the one (the square) relatively multiple (Fig. 11).

In Fig. 12 two black lines suggest a “square field” that is no sooner generated than it becomes an infinite space expanding beyond the canvas almost as though in an attempt to coincide with the infinite space evoked by the lines, that is to say, with the totality of space formerly expressed by the oval (Fig. 1).

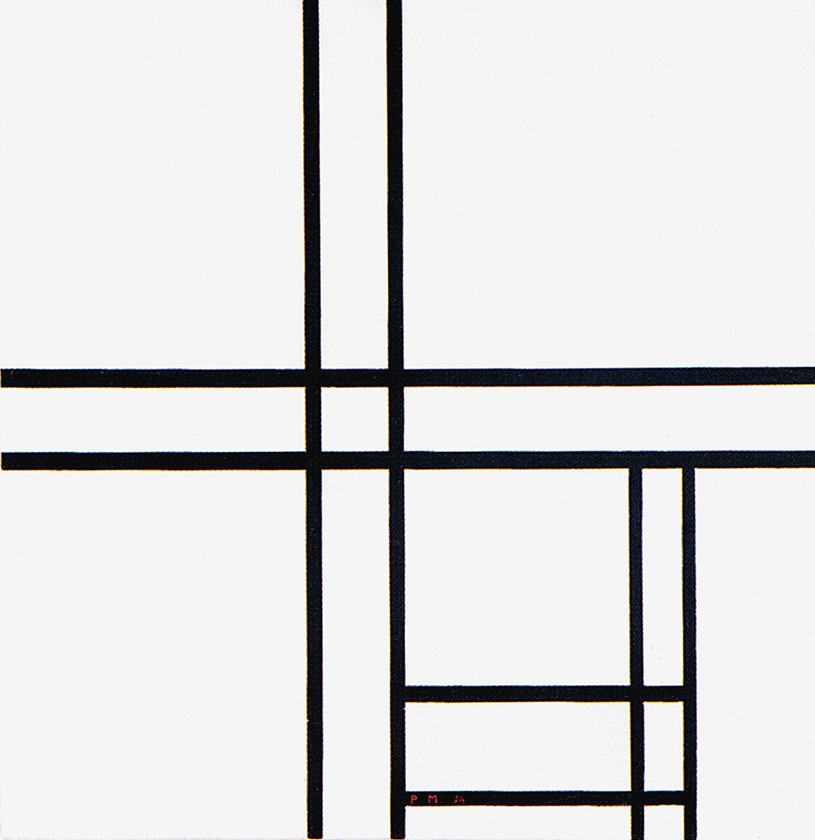

As from 1934, when the compositions gradually opened up once again to complexity, the lines blossomed into color (Fig. 13, 14, 15):

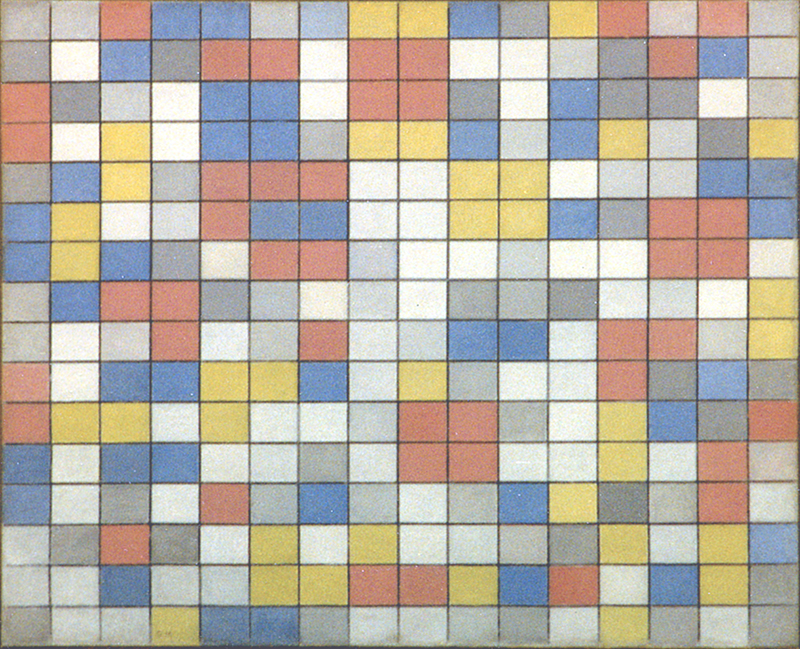

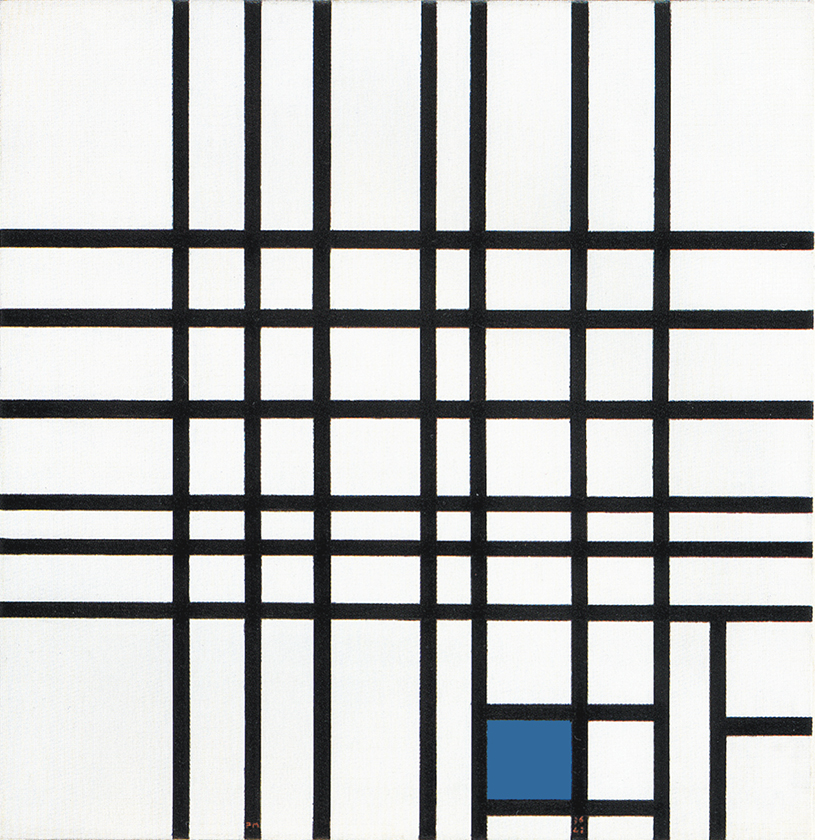

and then turned into a multitude of small squares and planes (Fig. 16) which then increased further in quantity and diversity (Fig. 17). At this point the sense of totality displayed in a virtual way by the continuity of the lines manifested itself in tangible and concrete form within the canvas (Fig. 17):

It was as though in VBW the lines had contracted to draw all of the variety virtually situated outside the canvas back into the painting.

Manifold space, formerly expressed as assumed and non-visible infinite extension (the continuity of the lines), gives way to manifold space understood as the largest amount of variation wholly visible inside the painting; variety that had not been seen since 1919; multiplicity that the painter had endeavored between 1920 and 1933 to drive beyond the canvas with lines in order to concentrate on a square unit designed to express both the one and the many at the same time; the albeit relative multiplicity of lines different in thickness each of which evoking a virtually infinite space.

From this viewpoint, the Neoplastic lines could be seen as a sort of “memorandum” serving for over twenty years as an ideal link between the representational space of art and the space of reality and then dissolving on the return of the latter (the great variety of planes in VBW).

While it is unity that alludes to virtual multiplicity in Lozenge with Yellow Lines, it is multiplicity that alludes to possible and never fully attained unities in Victory Boogie Woogie:

This is probably what Mondrian felt in his heart but was not yet able to explain clearly when he said that there was too much that was old even in Broadway Boogie Woogie.

While BBW does express a high degree of multiplicity, he probably saw something old in the fact that it was still necessary to evoke a part of reality virtually through the continuity of the lines. In talking about BBW, the artist is also said to have expressed dissatisfaction with the amount of yellow, which is tantamount to saying the same thing since yellow is the dominant color of the lines. He must have felt that lines were still excessively present. Lines are the primary means of expression in drawing, just as colored planes are in painting. The lines become planes in Broadway Boogie Woogie and everything is a plane in Victory Boogie Woogie.

Mondrian wrote as follows in a note sent to J.J. Sweeney on May 24, 1943: “Only now I become conscious that my work in black, white and little color planes has been merely “drawing” in oil color. In drawing, the lines are the principal means of expression; in painting, the color planes”.

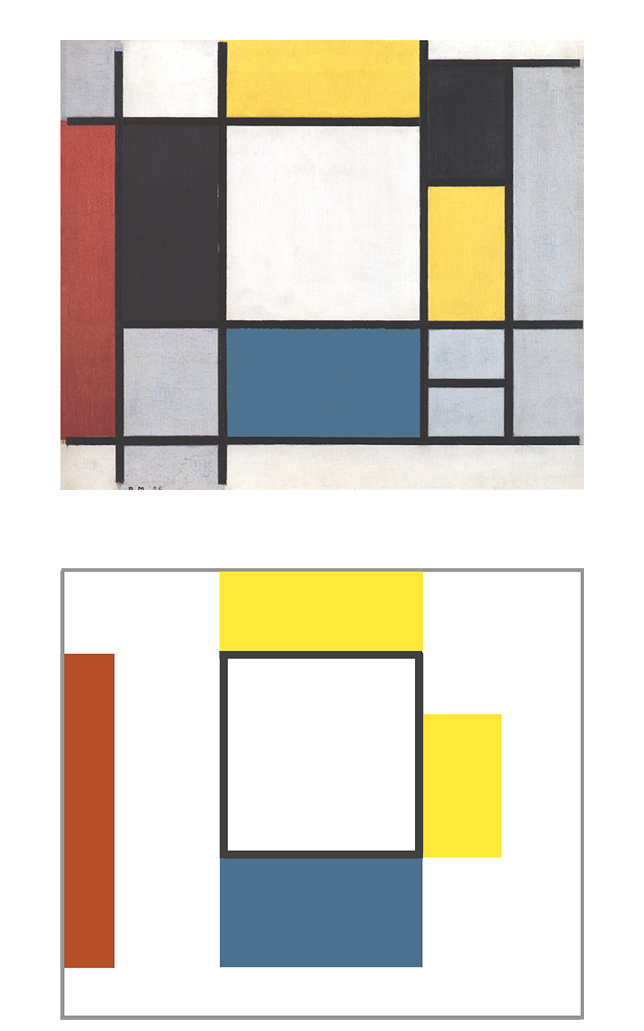

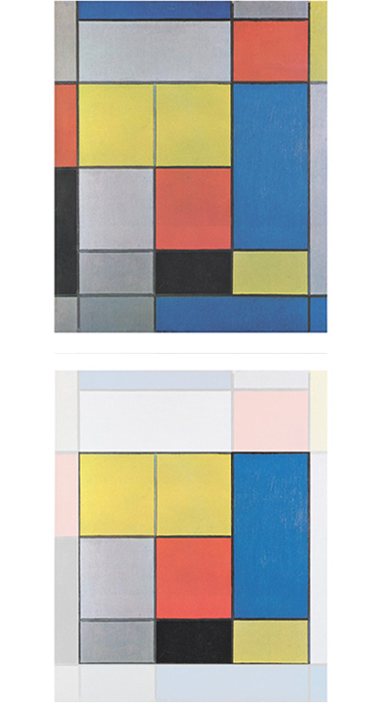

In the European Neoplastic compositions the black lines performed the function of drawing and the fields of color the role of painting. Drawing (lines) controlled painting (colored planes) from the outside with no participation, and painting accentuated and varied the proportions pre-established by drawing:

Sometimes a composition was reworked to rebalance form and color. Drawing and painting, intellect and emotion, engaged in dialogue but kept their distance.

In 1941-42 the black lines became colored lines:

1941-42

1941

1942

This means that drawing was born in paint and painting was already drawn and when, finally, the colored lines became planes in BBW and VBW, there was no longer any distinction between drawing and painting. In the last two works thought and emotion became one.

A wonderful process

The astounding consistency found in the Dutch master’s artistic trajectory brings to mind certain wonderful processes of nature that human thought has to trace back to a precise concatenation of causes and effects, in other words to a designing mind. I do not know whether nature really is based on a “design”, but if so then Mondrian, like all true artists, did nothing throughout his life other than act in spontaneous obedience to it.

The regular schemata used by Mondrian during the evolution of his work served to support the construction and definition of the new space that was slowly taking shape. Having taken the steps he felt necessary, the artist freed himself from the schemata just as a building is freed from the scaffolding that served to support it during the various phases of its construction:

The center of the composition, which had always been the key point for manifestation of the unitary synthesis:

lost its importance all along the pathway toward Broadway Boogie Woogie and Victory Boogie Woogie.

The regular layouts and proportional modules used to curb the uncontrolled development of form:

dissolved along the way. In the last works everything is in a state of becoming:

In Broadway and Victory Boogie Woogie one thing calls another and the first two become a third that gives birth to a process in which the only fixed elements are the orthogonal relationship and the five colors (white and gray included). All the rest is a free and unforeseeable development of elements differing from one another. The distinction between color and non-color drawn by Mondrian in the early 1920s had also disappeared by 1943, when everything had become color.

The Dutch artist chose his rules and schemata in complete freedom and followed them for just as long as he considered necessary. This is true freedom. In art, as in life, freedom is not the absence of rules, contrary to what some people believe. Freedom means being able to choose rules that are in any case necessary.

Mondrian worked throughout his life to adapt the reductive forms of the human mind to the far broader variety and variability of existence so as to maintain equilibrium between thought and nature.

Neoplastic space is born out of a vision that takes into due consideration the non-rational aspects of life and is therefore capable of generating a geometry that we can describe as organic but that is nevertheless expressed in the clear and precise forms of rational thought. Neither aspect must ride roughshod over its opposite.

This is typical of the artist’s way of proceeding: attaining a certain degree of synthesis and control and then opening up again to variability while always seeking to maintain a certain balance between the two aspects. Victory Boogie Woogie shows that the lines themselves—a crucial element of Neoplastic space for over twenty years—were no longer necessary.

It is difficult to imagine a geometry more flexible than this, so free in its innermost spirit as to reformulate itself continuously.

Beyond the canvas

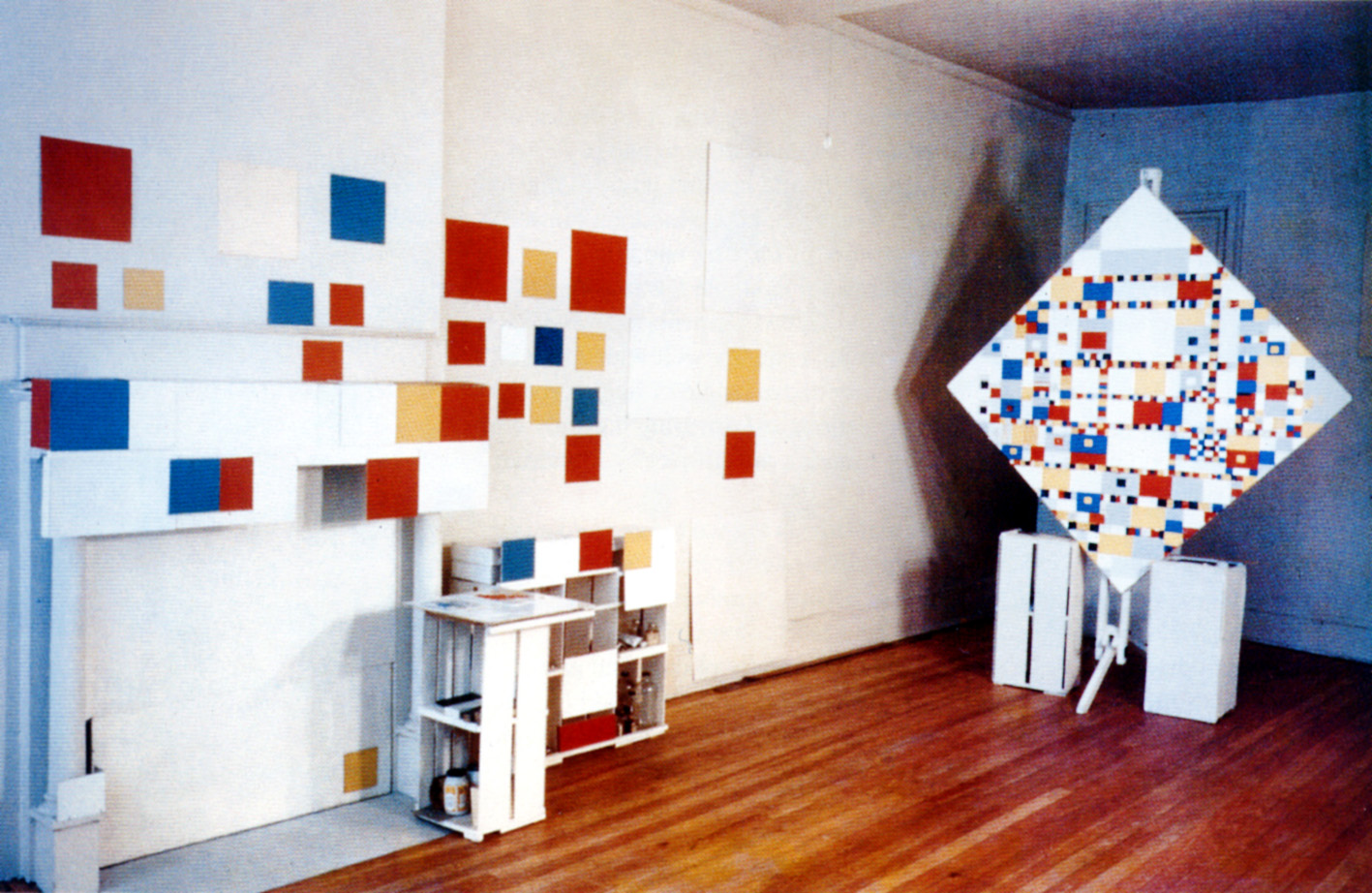

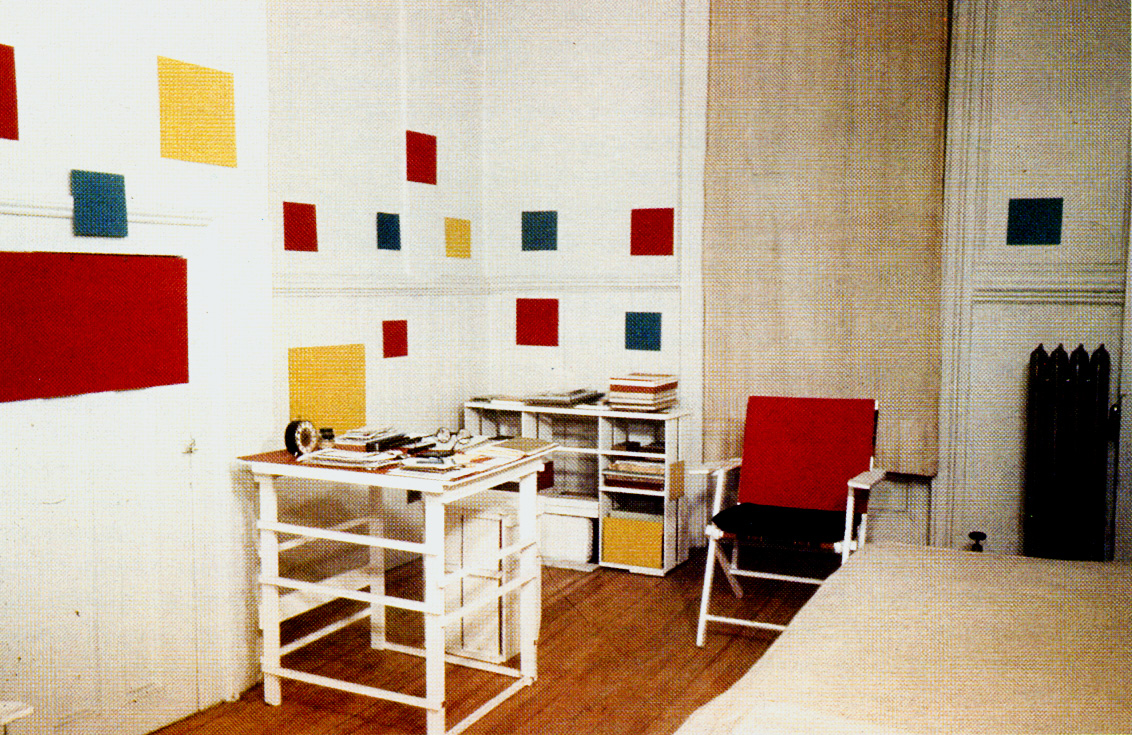

As in his ateliers in Paris, the artist worked also on compositions of colored rectangles juxtaposed on the walls of his New York City ateliers:

This can be interpreted as if the space of the canvas would open up to the space of reality. On the one hand, the multifarious aspect of the world populated the canvas (Victory Boogie Woogie); on the other, the subjective reality of art left the canvas and was transmitted to the world. Either way, the space of art became the space of life.

Victory Boogie Woogie is a sort of spiritual testament containing an exhortation addressed to future artists and mankind in general: art must be able to transform the discord of the real world into plastic harmonies serving as a model for the future developments of life; art must be able to improve the world.

Victory Boogie Woogie remains incomplete because every human action aimed at improving the world will necessarily be left unfinished. It is an open process that will never come to an end.

“By a duly notarized act Mondrian instituted Harry Holtzman his universal legatee. There has been much talk about this in the New York art circle even before Mondrian’s death since the artist had not made a secret of the donation. This will in favor of an American makes the works remain in their homeland of election where they are also the best protected against the decrees – “degenerated art”, “bourgeois formalism” – of the police regimes.”

Unfortunately, we still have people today who talk about “formalism” when dealing with Mondrian. (my note)

“On Monday, 24 January 1944, Hans Richter, a painter and film-maker, receives a card from Mondrian who, due to a bronchitis, declines an invitation to a cocktail. In point of fact at that time Mondrian was already affected by pneumonia. For two days the artist stayed at home all alone. Nobody would go visit Mondrian without making an appointment as the painter disliked being disturbed while working. Fritz Glarner heard about Mondrian’s health problems and decided to pay him a visit. He found the artist in very bad conditions, almost unable to speak.”

“Glarner asked Harry Holtzman to call a doctor who certified a very bad pneumonia. Against the artist’s will (Glarner and Holtzman will need one hour to convince Mondrian), the artist is brought to the hospital. Once in bed in a private room, he is happy and believes he will soon be cured. But the disease had progressed too far. For five days, Mondrian declined little by little.”

“On January 31, his condition is considered hopeless. Glarner and Holtzman kept watch over him all night. Miss von Wiegand came to visit. No one spoke and you could hear the faint gasp of someone who was working to get out of life. At 5 o’clock in the morning of February 1, we learn that everything is over.”

Michel Seuphor, Sa Vie son Oeuvre, Paris 1956

back to overview

Copyright 1989 – 2025 Michael (Michele) Sciam All Rights Reserved More